Claes Oldenburg’s status as a towering figure in Pop art who ranks alongside icons like Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol has been repeatedly reinforced in recent years, most notably with his second major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art last summer (the first one there took place more than 40 years earlier, in 1969). His iconic sculptures were a major focus of the recent, well-received Reinhard Onnasch show at Hauser & Wirth, and Paula Cooper gallery devoted a substantial portion of its Art Basel booth last June to 20 Oldenburg sculptures and drawings from the 1960s. The large-scale, monumental, and whimsical public sculptures he created with his late wife Coosje van Bruggen, are permanently installed at locales all over the US and Europe. Numerous art experts praise his skills as a master draughtsman. So why hasn’t his auction track record—particularly for his drawings and works on paper—kept pace?

One reason is scarcity. Large-scale permanent installations and commissions don’t turn up at auction, and even smaller sculptures, like his French Horns, Unwound and Entwined (2005), are rarely sent for public sale. With respect to drawings and works on paper, collectors are reluctant to let go of top-flight works, while sketches and studies often remain with the institutions behind the large-scale projects they relate to, such as the Walker Art Center, which owns nine related works for the monumental Spoonbridge with Cherry (1985–88) that graces its sculpture garden.

“Unfortunately its not uncommon when it comes to artists who are primarily known for sculpture that works on paper and other two dimensional traditional works almost always take second stage to the sculptures,” says Jeremy Goldsmith, director of the Americas for contemporary art at Bonhams. “In contrast to the exceptional prices for Oldenburg sculptures, there is substantial room for an improvement to this sector of his market.”

Other experts say there is a not-so-subtle bias toward paintings over sculpture in the upper echelons of collecting that extends even to related works, such as the drawings and works on paper.

“People will always assign a certain premium value to painters for the most part,” says Steven Henry, director of Paula Cooper Gallery. “Claes doesn’t make paintings. He is best known as an object-maker.”

At the recent spring auctions in New York, results for Oldenburg works were mixed. Christie’s contemporary day sale on May 14 included two Oldenburg lots,both of which sold. Empty Bag (Hard Bag) (1962), a small plaster, sold for $62,500 barely clearing the low end of the $60,000 to $80,000 estimate. Meanwhile, a 1967 work on paper, Woman Entwined in Giant Electric Cord, a graphite and watercolor on paper, did better, selling for $81,250, a solid price that exceeded the presale estimate of $40,000 to $60,0000. But at Phillips evening sale on May 15, a large, shiny Inverted Q—Black, 1976–88, estimated at $800,000–1.2 million, failed to elicit a single bid and was bought in. Last offered at Sotheby’s New York in November 1999, it sold for $332,500 on an estimate of $200,000–300,000. Another shiny black Inverted Q was featured prominently at the Onnasch show.

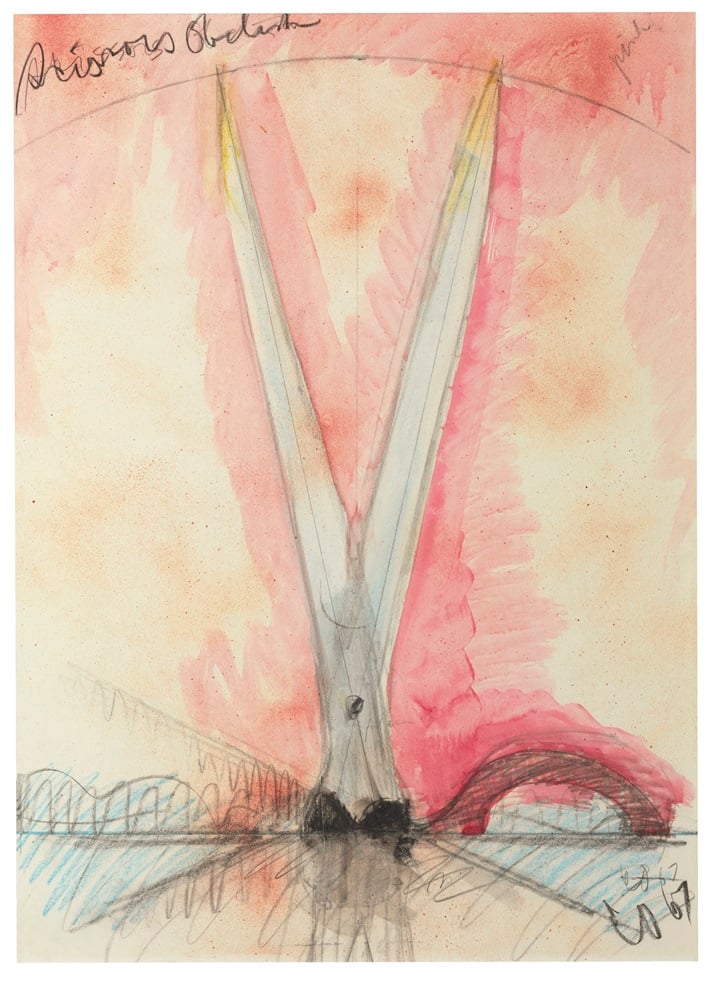

Claes Oldenburg, Blue Toilet (1965) sold for $475,200, at Christie’s in May 2006, a record for an Oldenburg work on paper.

Photo: Courtesy Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio © 1965 Claes Oldenburg.

At a time when the broader contemporary art market, and especially the market for Pop art, is at an all-time high, the current record for Oldenburg, who is 85 now and still working, is already nearly five years old; a price of $2.2 million was realized for Typewriter Eraser (1976), sold at Christie’s New York in May 2009, well above the high $1.8 million estimate. The second-highest price, $1.7 million, was achieved at Sotheby’s New York in 2008 for Yellow Girl’s Dress (1961), one of his iconic plaster works from “The Store,” the outpost that Oldenburg opened in 1961 on Manhattan’s Lower East Side where he hawked common, “everyday” objects like ice cream, oranges, cigarettes, hats, and shoes, all cast in plaster. Eager buyers snapped them up.

“Claes is a giant,” says Anthony Grant, Sotheby’s international senior specialist for contemporary art. Oldenburg “was really the sculptor of that first generation Pop movement, but we just don’t see much of his work on the market. It’s quite rare that we would have a great plaster piece from ‘The Store.’”

Oldenburg’s auction prices for sculpture are perhaps not such a far cry from those of his Pop peers: Warhol’s sculpture record is $4.7 million for a group of four boxes including a Brillo box; Indiana’s sculpture and overall record of $4 million is for a version of his iconic Love; and Lichtenstein’s sits at $5.4 million for Brushstroke. Not surprisingly, those artists’ records for paintings are far higher; $105.4 million for Warhol’s Silver Car Crash (Double disaster) (1963), and for Lichtenstein $56 million for Woman with Flowered Hat (1963), both realized last year.

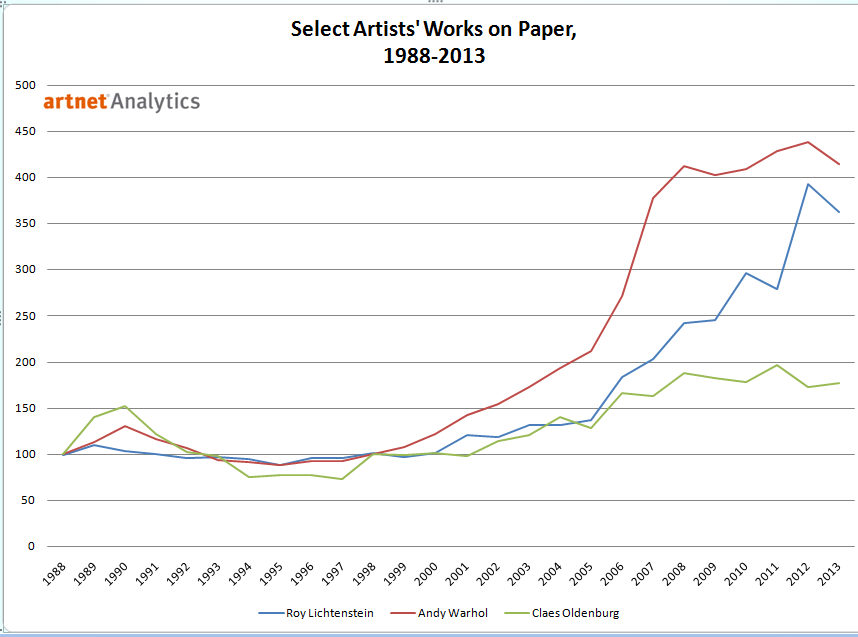

This chart shows the price performance of Claes Oldenburg‘s works on paper at auction vs. Pop art peers Warhol and Lichtenstein. Source: artnet Analytics.

But why is the gap considerably—and inexplicably—wider for prices of Oldenburg drawings versus those of his peers? As authors Richard Axsom and David Platzker point out in their catalogue raisonné of his prints and works on paper from 1958–1996, entitled “Printed Stuff” (Hudson Hills Press), drawing has always been an essential part of his practice.

“Why has drawing been so indispensable for an artist who became known primarily for his sculpture?,” they ask. “Drawing has been a generative tool for other sculptors but it takes on greater implications for Oldenburg because of the nature of his art.” As they note, Oldenburg makes objects from scratch—”I have always rebuilt the whole thing,” the artist once remarked. On a humorous note, they describe how Oldenburg initially shunned printmaking because he was daunted by the procedural aspect of it; he called it an “excruciatingly unpleasant activity, like going to the hospital for an operation.”

The current record for an Oldenburg work on paper is $475,200, realized for Blue Toilet (1965), a work in colored chalk, graphite, and watercolor, which sold at Christie’s New York in May 2006. By comparison, according to the artnet database, more than a dozen of Warhol’s works on paper have sold for over $1 million each (two have scored over $5 million each), as have about a dozen of Lichtenstein’s works on paper sold for over $1 million each.

“The market for Oldenburg’s drawings has been a bit of a mixed bag,” says Goldsmith from Bonhams. “The majority of the works on paper to come on to the market are sort of simple and quick studies, which do not feel like finished or polished works. The quality of these works are quite varied, which has led to fairly low prices and a decent amount of unsold works.”

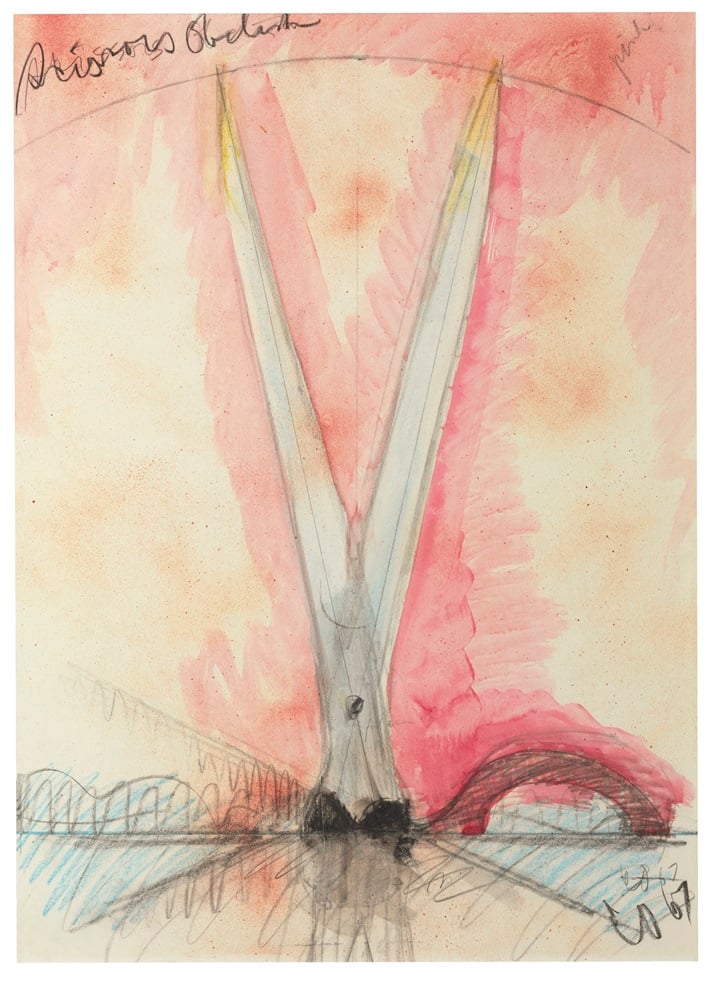

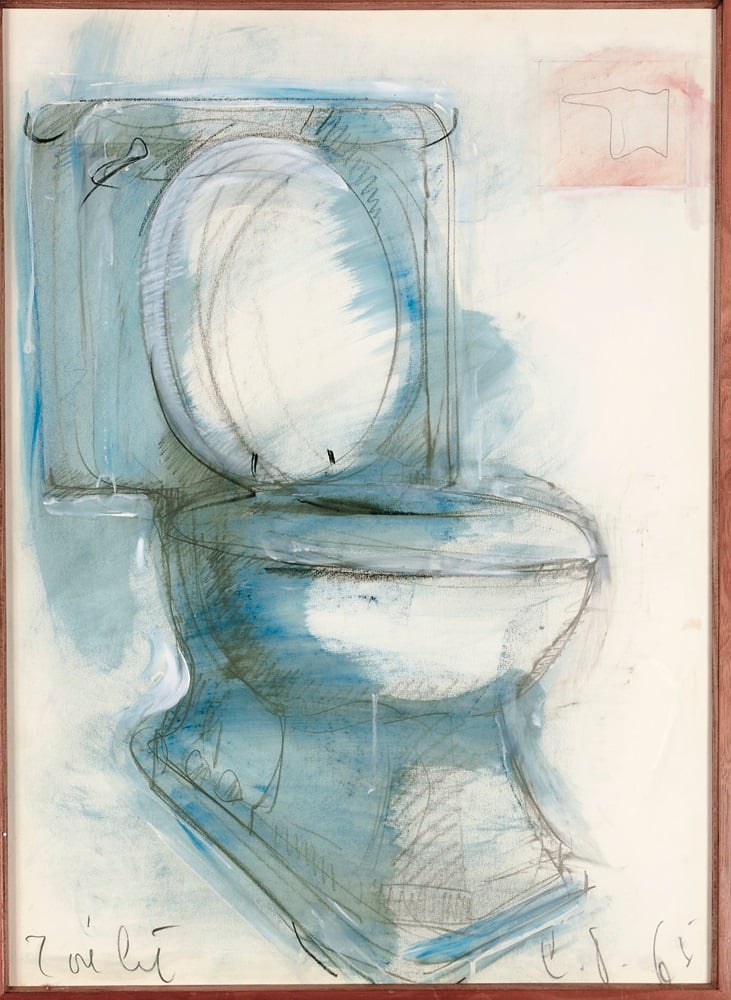

A look at 20 recent offerings of Oldenburg works on paper at auction from the artnet database shows quality and prices all over the map. They range from six bought-in, or unsold, works; a price of $338 at Cowan’s Auctions in Cincinnati last May for Geometric Mouse, Scale D (1971) on an estimate of $500–700; $99,750 at Christie’s New York, for Poster Study, New Media, New Forms I, Martha Jackson Gallery (1960) on an estimate of $40,000–60,000; and $267,750, also at Christie’s New York last May, for the watercolor, graphite, and wax crayon on paper Proposed Colossal Monument to Replace Washington Obelisk, Washington, D.C.: Scissors in Motion (1967). A roughly similar price in the range of $200,000, was confirmed by Steven Henry of Paula Cooper for a Scissors drawing sold at the Art Basel fair in Switzerland last year.

A look at Oldenburg’s most expensive works on paper over the years also shows a widely uneven range, indicating that auction specialists have trouble finding an accurate asking price, as for the top-selling Blue Toilet, which had a comparably modest $40,000–60,000 estimate. The second-highest price, $374,400 for the ink on cardboard collage on panel Big Cardboard Flag (1960) at Christie’s New York in 2006, also brought in multiple times the estimate of $40,000–60,000.

Says Bonhams’s Goldsmith: “On occasion beautiful examples of his works on paper do come on the market, which are in quite high demand. These works tend to be totally finished, executed with remarkable vision and technical skill and appropriately attract substantially more attention and achieve higher prices.”

![Scissors Monument Cut-Out (1967) graphite, crayon, watercolor on paper / collage was sold by Paula Cooper gallery at Art Basel last June for about $200,000. Photo: Courtesy Paula Cooper [chk]](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2014/04/COscissorsB.jpg)

Claes Oldenburg, Scissors Monument Cut-Out (1967) was sold by Paula Cooper gallery at Art Basel last June for about $200,000.

Photo: Steven Probert, courtesy the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio, ©1967 Claes Oldenburg.

Oldenburg’s images can be “sketch-y, text-heavy, almost poster-ish,” says Todd Weymann, director of prints and drawings at Swann Galleries, New York. “Despite the fact that art historically, he ranks as one of the first real innovators of Pop art, the imagery is not ‘hit you over the head’ like a Warhol Marilyn or Lichtenstein Crying Girl.” Weymann adds: “I’d certainly call it an under-appreciated market.”

Prices and demand for these works appear to be far more coherent and orderly on the private side, where, as Henry notes, there is little to no speculation. Drawings from the 1960s range, according to scale and subject, from about $125,000 to $250,000, while continuing on into the 1970s, notebook drawings can range from about $45,000 to $50,000 and upwards of $200,000, Henry says.

Sotheby’s Grant notes that most people are reluctant to let go of these. “You don’t see that many Oldenburg drawings because people love them and hold on to them,” he says. “Most of his drawing sales occurred earlier on in his career with Sidney Janis and Leo Castelli and they were carefully parceled out.” Further, many of the works stay with larger projects they are related to. “In recent years , Oldenburg hasn’t released a lot of drawings, especially when they refer to projects (typically the large scale outdoor public works). They go along with other bodies of work.”

“You can’t have a conversation about art of our era without Oldenburg,” Henry of Paul Cooper Gallery says. “He’s a consummate and expert draughtsman, one of the finest of his generation.”