Inside a warehouse in her hometown of Belen, New Mexico, Judy Chicago has assembled an archive of her entire creative output over the past 50-some years. Each artwork is carefully documented on one of thousands of index cards. Few artists have the foresight to keep such meticulous records from the very beginning. But Chicago always knew her work was worthy of careful attention, even if the rest of the world didn’t.

“I know the history of what’s happened to women artists’ work,” she told T magazine earlier this year. “One of my goals was to make sure that my work would not be lost. And I did not make an assumption that all would be taken care of.”

It’s taken decades for the rest of the art establishment to catch up to Chicago and fully grasp the breadth and depth of her work. For decades, she has been famous—perhaps too famous—for her monumental feminist masterwork, The Dinner Party (1974–79). But now, her broader oeuvre is increasingly commanding the attention of curators, dealers, and top collectors alike.

On December 4, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami is opening “Judy Chicago: A Reckoning,” a major survey of seven bodies of her groundbreaking work dating from the 1960s to the ’90s. The exhibition encompasses Chicago’s early feminist work as well as lesser-known series exploring the birth process and her own Jewish identity.

Meanwhile, at Art Basel in Miami Beach this week, San Francisco art dealer Jessica Silverman and New York dealer Jeanne Greenberg of Salon 94 will be showing a range of Chicago’s art, while Jeffrey Deitch and Larry Gagosian are including one of her early Minimalist paintings—at a reported $650,000 asking price—in their Miami show “Pop Minimalism: Minimalist Pop” at the Moore Building in Miami.

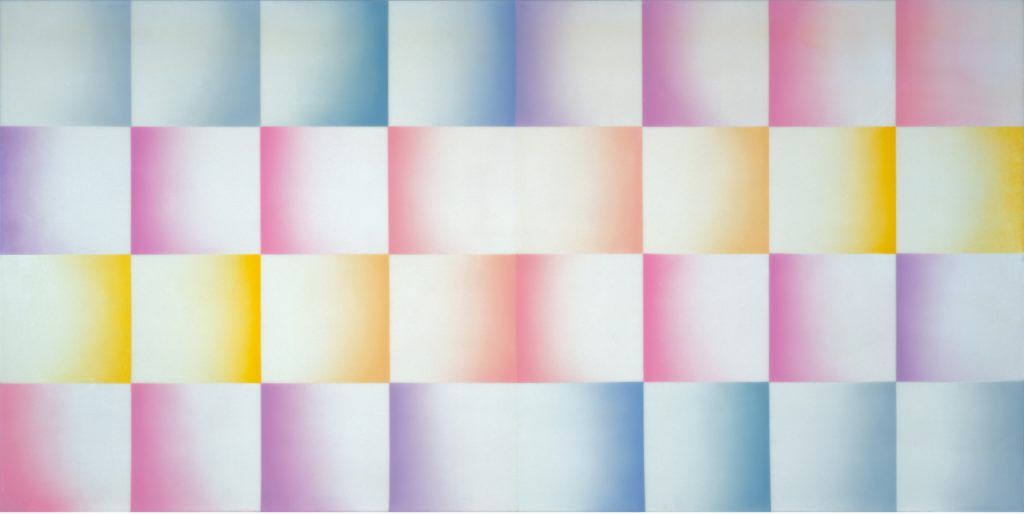

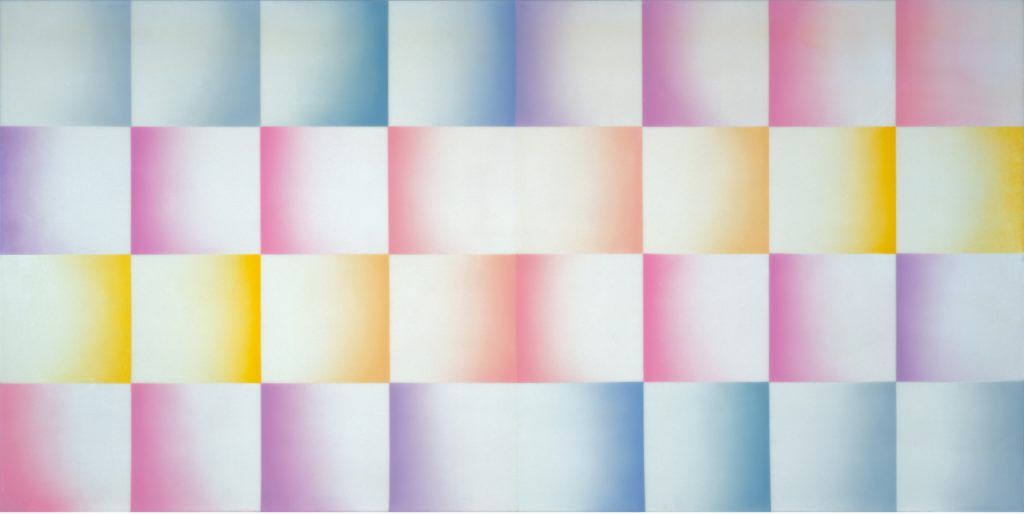

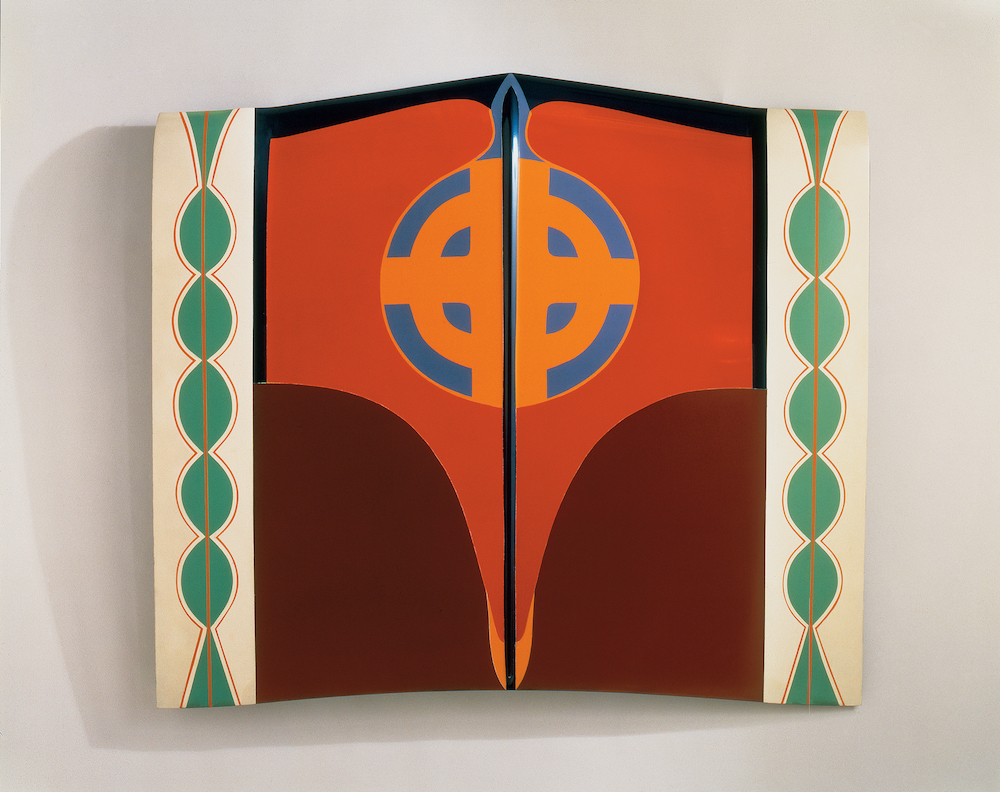

Judy Chicago, Flesh Fan (1971). [Sprayed acrylic lacquer on acrylic, 60 x 120 inches] © 2018 Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Courtesy of the artist, Salon 94, New York, Jessica Silverman, San Francisco. Photography by Donald Woodman.

Judy Chicago is one of many artists who, for decades, was ignored, her work dismissed as unfashionable or unsavory. So what happens when some members of the establishment finally come knocking? Such a correction, dealers and experts say, isn’t necessarily as easy, reliable, or sustainable as the buzz surrounding a museum solo show may lead you to believe.

A Fresh Start

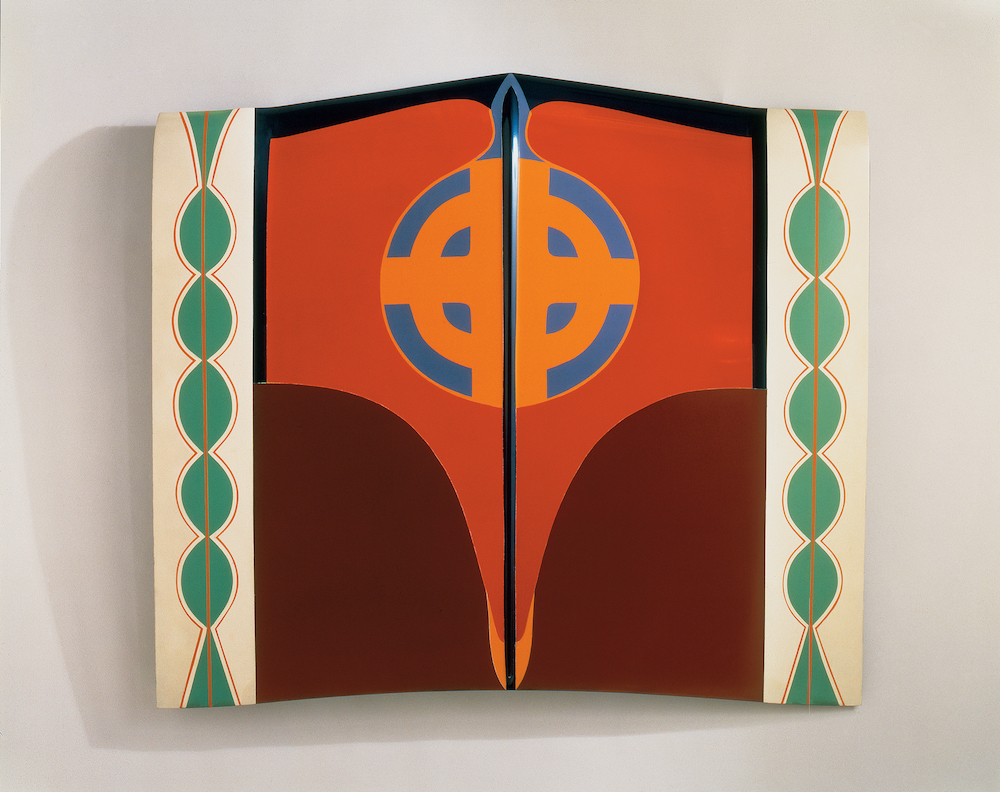

Many were first awakened to the diversity of Chicago’s oeuvre in 2011, when the Getty-funded initiative Pacific Standard Time included her in a variety of shows and revealed her important role in some of LA’s most famous art movements. Curators installed, for example, her slickly painted car hoods alongside Larry Bell’s pristine boxes and John McCracken’s shiny slabs.

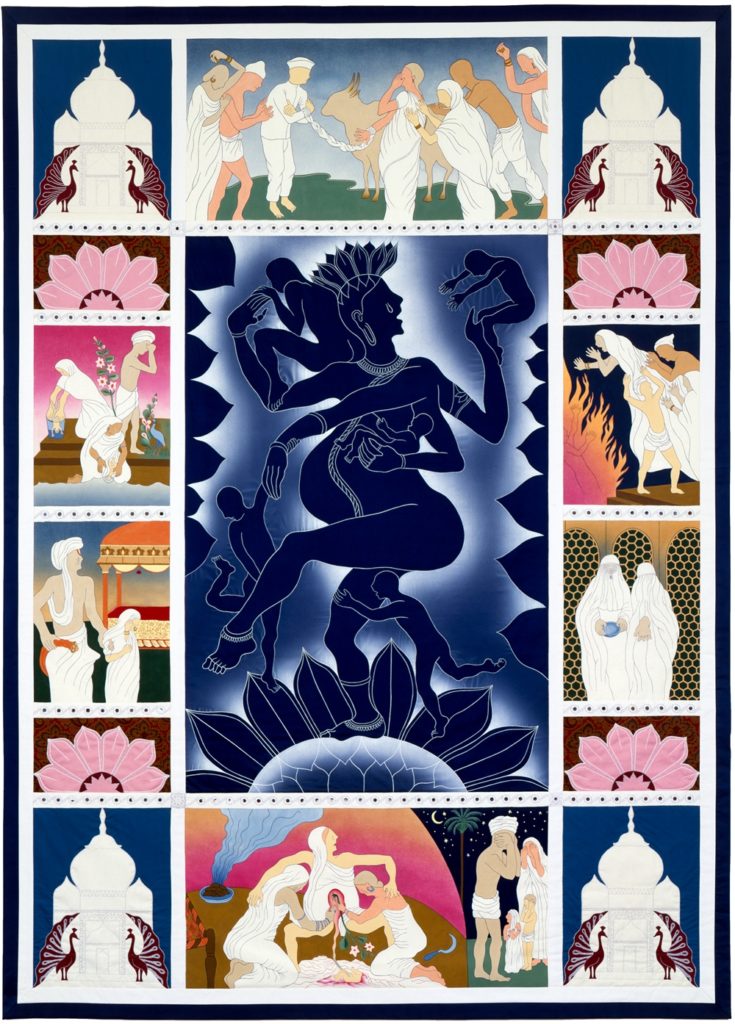

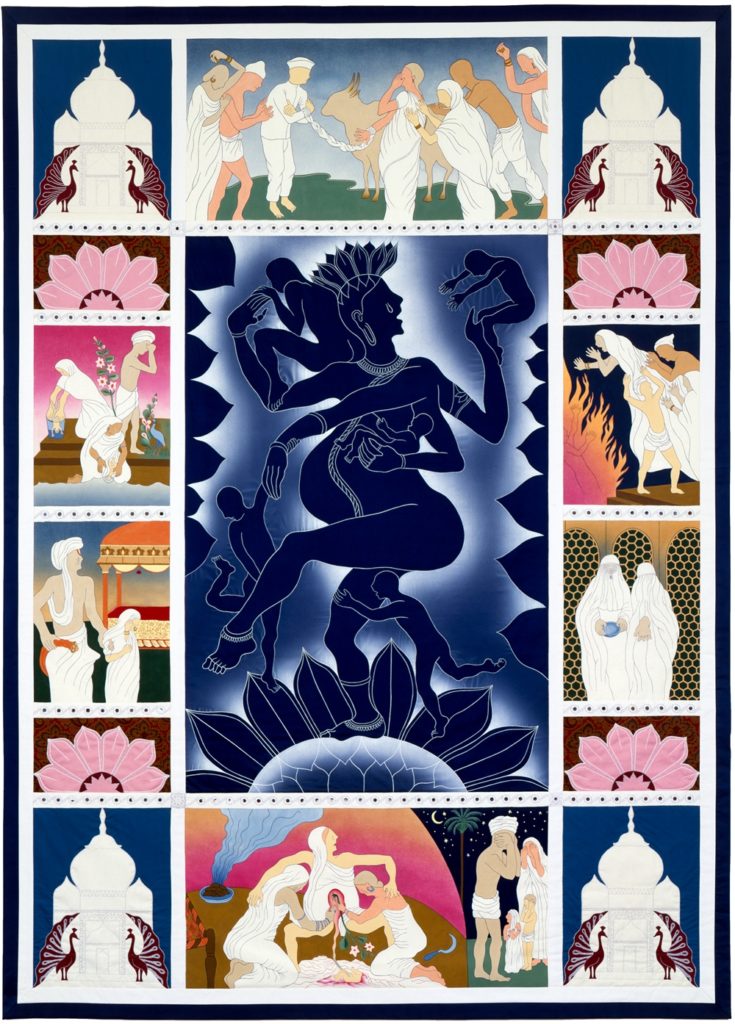

Judy Chicago EU-69 Mother India (1985). Image courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

Indeed, in the ’60s, Chicago worked to elbow her way into the LA art world’s boys club. But even when she went to auto-body school to learn to expertly paint car hoods or took pyrotechnic classes to create spectacular firework shows, she felt she wasn’t truly accepted. “Judy will be the first person to tell you that the response from her professors was not a positive one,” says Alex Gartenfeld, the artistic director of the ICA. “She loves to tell the story of how at least one famous curator would turn his back when he saw her work in the room.”

The biomorphic imagery on her car hoods did not endear her to the “male professors that she had at UCLA in the late ’50s who were working in Abstract Expressionist style,” he adds. As Chicago progressed and began to focus on directly communicating her feminist principles, “her work became more didactic and specific. She did not feel a warm reception from the decision-makers in the art world.”

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Chicago explained that she felt she had been a victim of “covert censorship, where the only work of mine allowed to see the light of day in terms of real visibility is The Dinner Party.” The massive, triangular banquet table with 39 place settings honoring important women from history has been a prominent, divisive feminist symbol for decades and has been permanently housed at the Brooklyn Museum since 2007. But all the while, “my roots in Southern California and my participation in the art scene here have been erased,” Chicago said.

Judy Chicago, Hypatia test plate #9 first version, (1975–78). Image courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery.

A New Audience

Now, however, that story is changing. Greenberg’s New York-based gallery Salon 94 first began working with Chicago a few years after Pacific Standard Time, around 2014. “We spent a lot of time talking about what bodies of work we really needed to get out there in the world,” Greenberg says.

It helps that the earnestness, anger, spirit of collaboration (Chicago often teamed up with artisans to create elements of her vastly ambitious projects), and political conviction in her work are now very much in vogue. “Obviously the work is brilliant and prescient, and way ahead of its time,” dealer Jessica Silverman says. Now, she adds, it is appealing to a new, younger generation who “have been driven toward feminism” in the Donald Trump era.

Some of Chicago’s works feel positively clairvoyant now. Her series “PowerPlay,” which depicts distorted male bodies and faces as an exploration of power and privilege, was greeted with crickets when it first debuted in the ’80s. But when she recently posted photos on Instagram from the series alongside the twisted faces of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and Senator Lindsey Graham, she noted: “It is really sad to watch my paintings come true decades after they were created.”

Chicago continues to revisit the forms she developed early on. In February 2019, ICA Miami will present a newly commissioned site specific “Smoke” piece titled Purple Poem (for Miami) that draws on the artist’s iconic performance works from the ’60s in which she used smoke machines to create ghostly environments. Another commission is a rainbow block sculpture titled Rearrangeable Rainbow Blocks (1965) which consists 12 rearrangeable blocks (automotive lacquer on aluminum) that will be shown in ICA Miami’s sculpture garden.

“The principles of allegory, her treatment of the figure, and use of color, which seemed either provocative or out of date for decades, now feel really fresh,” Gartenfeld notes.

Judy Chicago, Birth Hood (1965/2011); © Judy Chicago/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo ©Donald Woodman/ARS NY Courtesy Salon 94, New York, and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco

With the benefit of hindsight, Chicago’s admirers also hope collectors and the public will come to recognize her technical prowess. “When people think of The Dinner Party, they think of it as an incredible theatrical set,” Gartenfeld says. “But they don’t think about the formal properties of the work itself.”

The ICA show will include several ceramic test plates, which Gartenfeld hopes will provide “an opportunity to see Judy’s hand and her approach to the medium in a way they haven’t seen before.” And her underrated skill as a draftsperson will be evident in Autobiography of a Year, a suite of more than 150 drawings Chicago created in response to a particularly harsh critical reception of the Holocaust Project, an exploration of Jewish history that involved eight years of research.

Market Moves

Dealers say that some might be surprised at how accessible some of these works remain considering the recent flurry of attention surrounding Chicago. “People don’t imagine they can buy anything from the Dinner Party,” Greenberg says. Ceramic test plates, which are unique, range in price from $175,000 to $200,000.

Salon 94 is bringing several of Chicago’s works, including an early minimalist painting and Mother India (1985), pictured above, to Art Basel Miami Beach. Prices range from $100,000 to $650,000 for the works at the fair.

Silverman is also presenting a Dinner Party plate in Miami, titled Hypatia, named for a Hellenistic philosopher and mathematician who advocated for women during her lifetime, as well as the artist’s expertly executed small drawings from the late 1970s, which range from $28,000 to $45,000.

Chicago, who designed the Dinner Party with populism in mind, has also embraced bringing her images to a broader audience by wading into the retail sector. This week, Max Mara is unveiling a limited edition t-shirt based on Chicago’s Bigamy car hood and designed in its institutional colors of camel, navy and red ($245).

The t-shirt officially launches December 3 during the opening of the ICA show, for which Max Mara is the presenting sponsor. Earlier this year, Chicago also launched a line of limited edition plates, inspired by The Dinner Party, in connection with the Prospect NY ($135–155).

It seems the exposure is starting to make an impact. “Now when I talk to people about Judy, they’re much more specific,” Silverman says. “They want a painting from the ’60s, for instance, or an atmosphere work.”

A Ways to Go

While dealers say Chicago’s prices are trending upward on the primary market, the auction market remains thin, and skewed toward the lower end.

Of just 61 works offered at auction, according to the artnet Price Database, some 16—or 26 percent—went unsold. The lowest price on record is just $275 for a 1965 silkscreen, while the highest is $288,000 for a 1964 car hood that sold at Los Angeles Modern Auctions over a decade ago, in May 2007. The second-highest price is a fraction of that—$60,000 for an early minimalist painting. Several sources told artnet News those paintings are now averaging $500,000 and up on the private market.

“If there were 10 more car hoods on the marketplace right now, I think we would see those shooting into the millions,” says Peter Loughrey, the director of modern design and fine art at Los Angeles Modern Auctions.

Until recently, Loughrey says, there was very little interest in Chicago’s work, “other than a few dedicated private collectors and institutions.” In the end, he thinks the lack of supply for Chicago’s most significant work, much of which is already in museum collections, may hold back pricing momentum. “The market value is never going to be tested and retested because they just won’t show up for sale,” he says.

Judy Chicago Car Hood (1964). Courtesy of Los Angeles Modern Auctions.

But he still thinks there is room for Chicago’s market to grow on a smaller scale. Given the “interest in reassessing artists that have been overlooked because of race or gender or any other status that precluded them from major attention, the marketplace will catch up very quickly,” Loughrey says. “It has been rewarding a younger generation of artists almost faster than the original generation of artists like Judy who spearheaded this movement.”

Arnold Lehman, the former director of the Brooklyn Museum and current advisor to Phillips auction house, notes that a number of institutions have now made major acquisitions of Chicago’s work, including the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. And in June 2019, her latest series, “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction,” will be the subject of an exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.

Now that museums are “taking a look at the amazing and enormous contributions of women artists who were entirely overlooked,” Lehman says: “It’s Judy time.”

“Judy Chicago: A Reckoning” is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, from December 4 through April 21, 2019.