The Art Detective

Undervalued Pop Legend James Rosenquist Is Having a Moment

MoMA and a Michelin-starred restaurant are spotlighting the artist, as Phillips readies a special sale of his prints.

MoMA and a Michelin-starred restaurant are spotlighting the artist, as Phillips readies a special sale of his prints.

Katya Kazakina

James Rosenquist is having a moment in New York, and not a moment too soon.

You can enjoy the late Pop artist’s dynamic, collage-like paintings while savoring black caviar and foie gras underneath the soaring coffered ceiling at Daniel, chef Daniel Boulud’s two-star Michelin restaurant on the Upper East Side.

Or you can walk a few blocks south on Park Avenue to see Rosenquist’s masterful prints at Phillips auction house, ahead of a live sale on February 15, with estimates as low as—gasp!—$400.

The Museum of Modern Art installed Rosenquist’s monumental 2011 painting The Geometry of Fire in its lobby this week—a big deal, as we all know. An even bigger deal: Upstairs, his 86-foot-wide tour de force, F-111 (1964–65), takes over an entire gallery, at once a painting, environment, and commentary on consumer culture and the Vietnam War. (The painting’s dimensions match the length of the F-111, a fighter-bomber then in development.)

But that’s not all. Down by the New York Public Library, Castelli Gallery has mounted another epic Rosenquist, the 40-foot-wide The Holy Roman Empire through Checkpoint Charlie (1994), which was inspired by the fall of the Berlin Wall.

James Rosenquist, The Holy Roman Empire through Checkpoint Charlie (1994). Photo courtesy of Castelli Gallery.

“It’s just kind of a great coincidence that all these wonderful events are happening at once,” said Mimi Thompson Rosenquist, the artist’s widow. “We were working on different things and they all ended up happening at once.”

More is in the pipeline. There will be a doubleheader of Rosenquist and French Pop artist Alain Jacquet (1939–2008) at Perrotin’s New York gallery in November and a solo exhibition in Seoul at Thaddaeus Ropac in late in the year, according to Mariska Nietzman, the executive director of the Kasmin gallery, which began representing the Rosenquist estate in 2021.

The flurry of activity could not be better timed. Rosenquist’s champions worry that a new generation of art buyers barely knows his name or understands the significance of his work.

“Young collectors don’t know Jim at all,” said John Corbett, who is involved with the Rosenquist estate. “He’s not hot at the moment. So, we wanted to get his name out there and celebrate him.”

The artist, who died in 2017, remains shockingly undervalued next to peers like Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein. It’s almost incomprehensible, given the acclaim Rosenquist got early in his career, his solid place in the canon of postwar American art (he is in at least 69 public collections), his prominent dealers, and the countless museum exhibitions that have featured his work.

I asked a friend who is steeped in the art world to guess Rosenquist’s auction record. After a brief reflection, my friend said: $50 million?

It would make sense, considering the auction records of his contemporaries: Warhol ($195 million), Lichtenstein ($95.4 million), Johns ($55.4 million).

But Rosenquist’s record is $3.3 million.

That’s right. (Trust me, I triple checked.)

Probably like you at this very moment, I was shocked to see this number next to his name. We are not alone.

“I felt the same way,” said Bill Acquavella, the patriarch of the Acquavella family of dealers and the head of Acquavella Galleries, which showed Rosenquist for more than a decade until his estate moved to Kasmin.

“I thought his pictures were really undervalued,” Acquavella said by phone from Palm Beach, Fla. “I don’t have an answer for that. He was a colleague of all these Pop artists. He knew them all. When they started, he started.”

Art adviser Janis Gardner Cecil and chef Daniel Boulud at Daniel in New York, with James Rosenquist’s Females and Flowers (1984) behind them.

Rosenquist’s market faced idiosyncratic challenges for years. His most significant Pop art paintings, from the 1960s, should be selling at a huge premium to his current prices, but they are mainly in museum collections and are unlikely to come to market. Their massive scale may be another complication; after all, billboards can be tricky to fit in most apartments.

Recently, demand in the art world has shifted towards figurative work by Black and female artists, and away from already acclaimed white male postwar masters. That makes it more difficult to revive the secondary prices of someone like Rosenquist, experts say. Primary-market prices for his paintings start at $500,000, Nietzman said.

Rosenquist’s annual auction sales have been erratic, spiking to almost $8 million in 2014 and 2019 and retreating to $3.6 million in 2023. In May, his 1962–63 painting Fast Pain Relief, from the collection of real-estate developer Gerald Fineberg, failed to sell with an estimate of $1.5 million to $2 million. Arguably, that was not a great painting. In November, a better example, Dog Descending a Staircase, a witty 1979 nod to Marcel Duchamp, fetched $736,600, surpassing its estimated range of $500,000 to $700,000.

Born in Grand Forks, N.D., in 1933 to a father who was an amateur pilot and a mother who was an artist, Rosenquist moved to New York at the age of 21 on a scholarship to the Art Students League.

Like many of his peers, Rosenquist had a background in commercial art, painting signs and billboards around Times Square. That experience would shape his visual language in terms of process and scale. He used images from advertisements and magazines to create dynamic compositions on a massive scale that would overwhelm the viewer and disrupt the traditional picture plane. Romance, economics, environment, politics, philosophy, the cosmos—he seemed to leave no theme unexplored.

“He is very much a visual poet,” wrote curator Walter Hopps, who organized Rosenquist’s 2003–04 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum. “Sometimes his poems are epic; sometimes they are vast in subject or in scale—but they are still poems… He orchestrates combinations that seem absurd—a French horn and a black hole—but those combinations also make a curious sense, both formally and psychologically.”

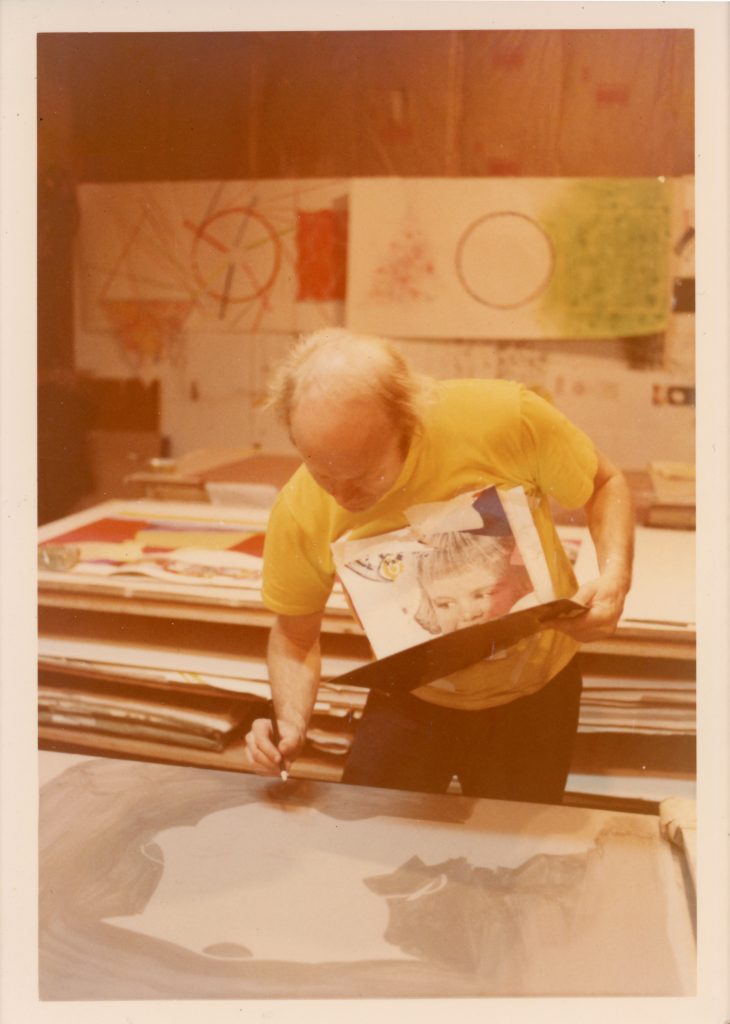

James Rosenquist working on the print F-111 (1974) in his East Hampton, New York, studio, 1974. Courtesy of the estate of James Rosenquist.

Such tensions are palpable in The Holy Roman Empire through Checkpoint Charlie, created in the wake of the artist’s visit to Berlin in 1992. He was surprised to discover that “West Berlin was full of life and color, and the East was all gray,” said Barbara Bertozzi Castelli.

She first saw the work at her late husband Leo Castelli’s gallery in 1994 (the legendary dealer represented Rosenquist from 1965 until his death in 1999). She was blown away by its poetic title and cataclysmic imagery: flaming wings of Nike, the Greek goddess of victory, a giant red eye at center, the sculptural and architectural elements evoking German history, from its heyday under Frederick the Great to its World War II defeat through the Soviet occupation.

“You see these images and you realize they cannot be expressed in any other way,” Bertozzi Castelli said. “The work is so powerful.”

The painting’s European owner recently offered it to Bertozzi Castelli for resale. The work’s historical focus resonated with her amid the world’s current political turmoil, the wars in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, and the looming Trump-Biden presidential rematch in the U.S. So she brought it to New York, where it’s on view through April 16. The asking price is $2.9 million, she said.

The exhibition at Daniel restaurant is part of its biennial art program, curated by art adviser Janis Gardner Cecil. Boulud and Rosenquist were “good friends,” the artist told me when I interviewed him for Bloomberg News in 2010.

“It’s amazing how you meet people through other people,” Rosenquist said. “I knew a racecar driver, Stefan Johansson, who was very hot. He introduced me to Jean Todt. He introduced me to a French doctor. He introduced me to a French architect who redid the Louvre with I.M. Pei. He introduced me to Daniel Boulud.”

In 2010, Rosenquist created Team USA’s poster for the prestigious international culinary competition the Bocuse d’Or, at Boulud’s request. The chef supplied gourmet lunches and suppers to Rosenquist while the artist was in a hospital after knee-replacement surgery.

“The chocolate desserts I gave to the nurses,” Rosenquist told me. “They all loved me.”

Now the tables have turned, and love is being gushed on the paintings. “The response at Daniel has been nothing short of remarkable,” said Gardner Cecil.

Rosenquist’s thematic richness is on full display at Phillips, which collaborated with his estate to present a chronological evolution of the artist’s printmaking from 1965 to 2012.

“Rosenquist was quite a prolific printmaker,” said artist Cary Leibowitz, whose day job is being worldwide co-head of editions at Phillips. “He worked very fast. He learned how to improvise, sometimes inventing new techniques because he just wanted to get the piece done the way he wanted it done, and broke whatever rules needed to be broken.”

James Rosenquist, F-111 (G. 73) (1974), which is being offered by Phillips later this month. Image courtesy of Phillips.

For example, his Small Doorstop (1963–67)—a red and white floorplan of a typical three-bedroom house in postwar America—is displayed up on the ceiling, facing down, with three light bulbs attached. The work comes from an edition of ten. It’s estimated at $80,000 to $120,000, the most expensive lot in the sale. (Another work from the edition went for $137,000 at Christie’s in 2017.)

On the opposite end of the price spectrum is Whipped Butter for Eugene Ruchin, from 11 Pop Artists, Volume II (G. 11), a 1965 work inspired by a visit Rosenquist made to Leningrad to meet Soviet nonconformist artist Eugene Ruchin, who was his penpal. The work, with its flat masses of red, blue, and yellow, evokes Soviet propaganda posters from the 1930s. From an edition of 200 plus 50 artist’s proofs, it’s estimated at $400 to $600. (That’s not a typo!)

Also on offer is a complete set of four monumental lithographs, F-111 (south) (west) (north) (east) (G. 73). Created in 1974, they explore the same imagery as Rosenquist’s iconic painting, including the bombardier, a girl underneath a hair dryer, swirls of spaghetti, and lightbulbs. It’s estimated at $30,000 to $50,000.

These estimates are modest, to say the least. In recent years, a work by an untested emerging artist right out of art school would cost as much.

“I don’t think anyone really put their finger on why different generations wax and wane on different artists,” Leibowitz said. “Rosenquist, Rauschenberg, Oldenburg are priced to sell these days. Even if people pay three times the estimate, they are still getting a bargain.”