Art Fairs

In Hong Kong, Team Gallery’s Jose Freire Says Goodbye to Art Fairs—and Reveals What He’s Going to Do Instead

The New York dealer will invest in a bigger space in Los Angeles, the gallery's exhibition program, and publications post fairs.

The New York dealer will invest in a bigger space in Los Angeles, the gallery's exhibition program, and publications post fairs.

Andrew Goldstein

Bounding around his booth on the second day of Art Basel Hong Kong, the last art fair he says he’ll ever do, the veteran New York gallerist Jose Freire had the lighthearted, unburdened air of a college senior at graduation week. He’s become a big man on campus, too: ever since he gave an unusually candid interview to artnet News, explaining in great detail why the math behind participating in art fairs had become unsustainable for his Team Gallery, he’s been inundated by Instagram direct messages and emails from fellow dealers grateful that he broke the ice on the subject. “Gallerists complementing gallerists is really kind of touching,” he said.

“I’ve gotten notes, some as many as four pages long, from many people expressing a similar dissatisfaction with the way the system works,” Freire continued. “I’ve done 13 Art Basels, 13 Art Basel Miamis, and three of the Hong Kong fairs. I recently added it up and realized it all had cost me twice the budget of Moonlight.” He paused to let that sink in. (The film cost $1.5 million.) “I have faith in my program, and I can’t allow this mechanism to erode that faith.”

At the same time, Freire made it clear there was no bad blood between him and the fair. “Marc Spiegler came into my booth immediately during the install and we had a perfectly lovely interaction,” he said of the Art Basel director. “They didn’t do it. If we could find the culprit it would be great, because then we could say, ‘Aha, we’ve found the culprit!’ But no one’s the culprit.”

Instead, the source of the crisis many dealers feel themselves caught up in remains frustratingly amorphous. “Since I’ve started working in the art world there have been many crashes, and we used to always call them what they were, which was crashes,” Freire said. “Here, no one wants to say it’s a crash because the poles weren’t affected. A lot of it is just tied up with shrinking attention spans in the digital age.”

Since his interview made him a sort of accidental spokesman for the middle-market gallery crunch, Freire has tried to think of some possible measures that could help the situation. Should a fair like Art Basel could create a special section for mid-career galleries, where booths fees would only cost half-price? No, he realized, because then the galleries would come off as charity cases. “There’s no solution,” he concluded. “I think there just have to be a lot of individualized approaches to the problem.”

Online doesn’t offer any immediate hope, either. “You cannot take an Amazon approach to contemporary art, because it doesn’t protect the artist or the value—and you need to protect the artist, and a dealer needs to protect the value of the art they’re selling to to their collectors,” he said. That said, he noted, the VIP Art Fair model held some promise when it debuted in 2011 as a virtual souk with far lower costs to dealers—but that venture went down in flames because insufficient server capacity caused the site to crash both times it was attempted. “That idea happened too early,” Freire said. “I’d like to see someone take another crack at it.”

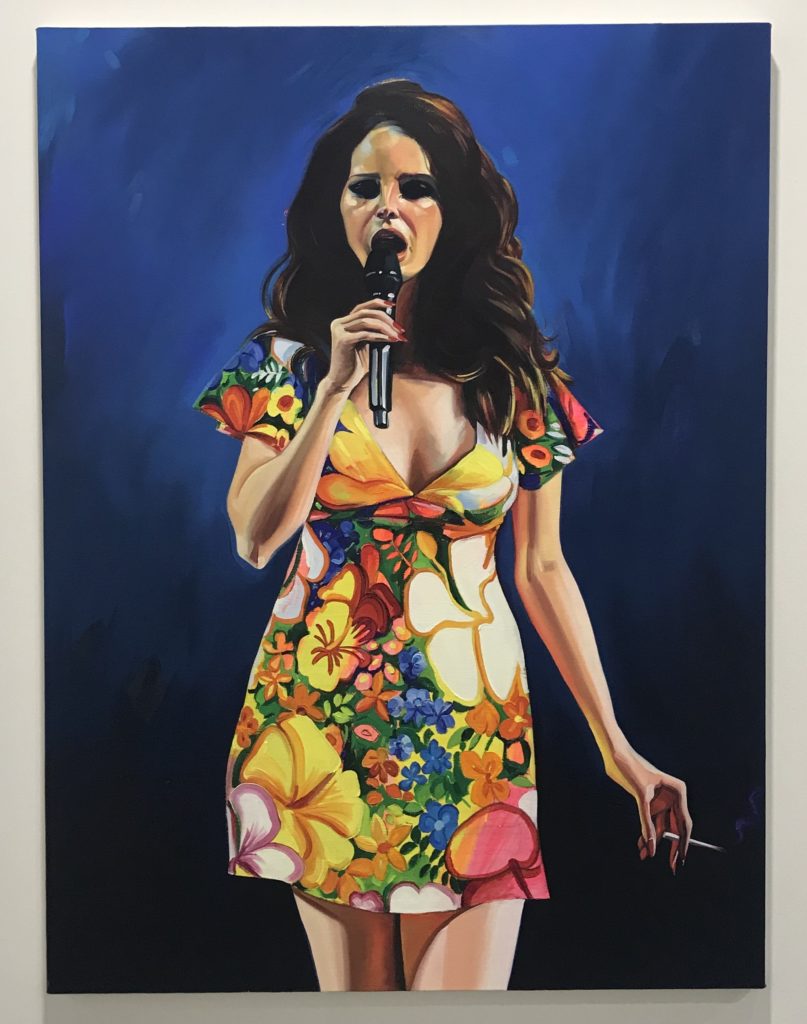

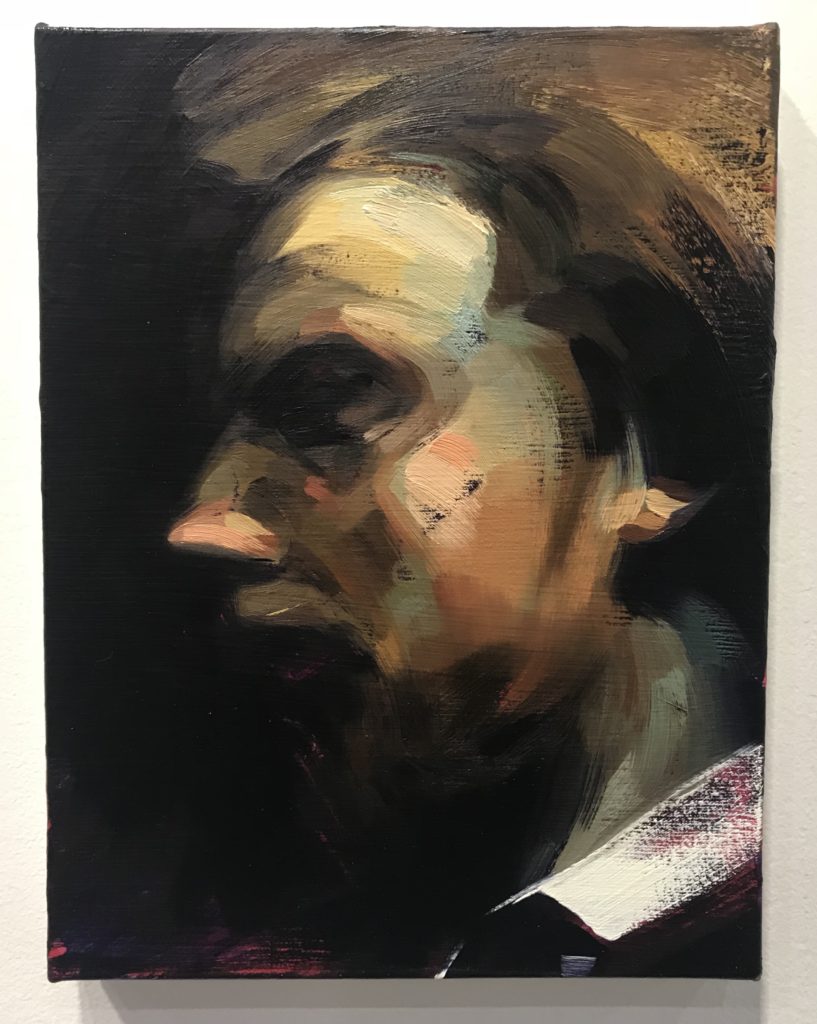

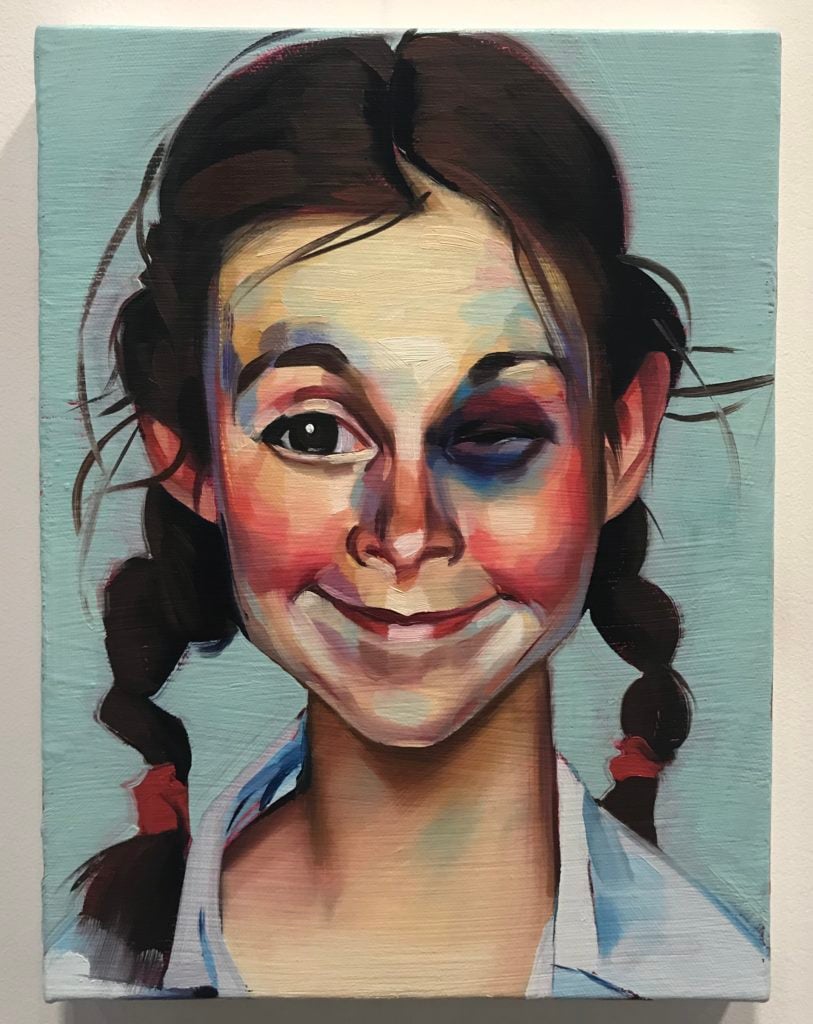

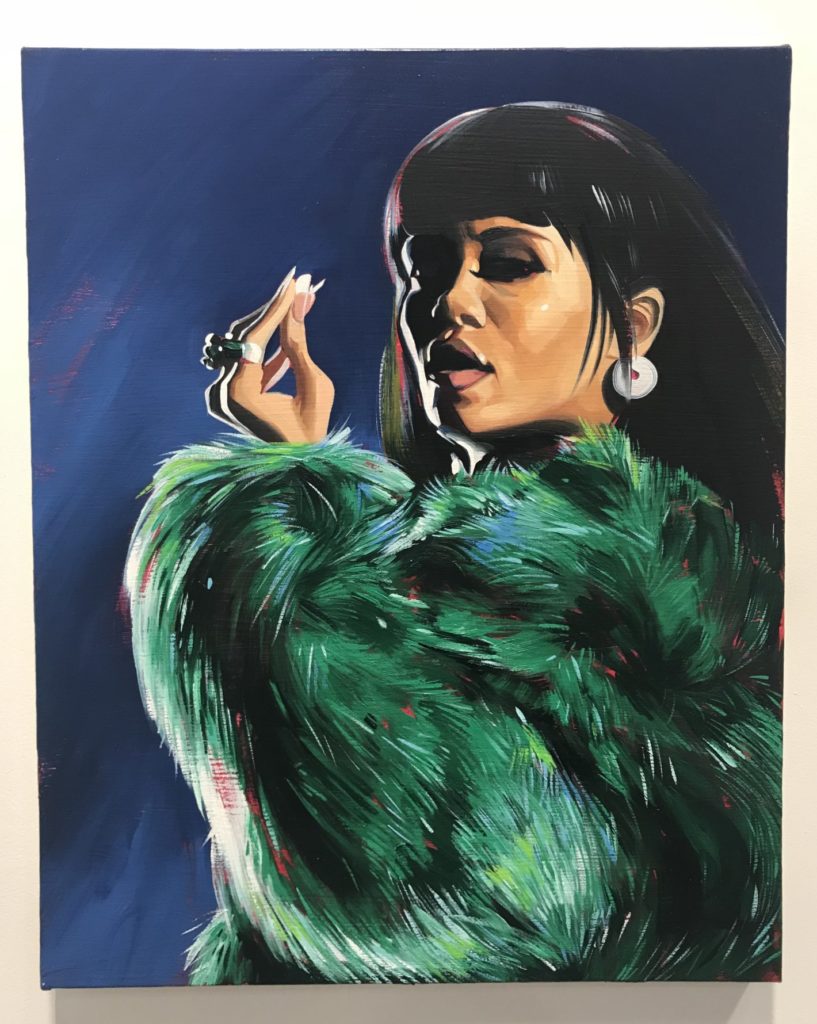

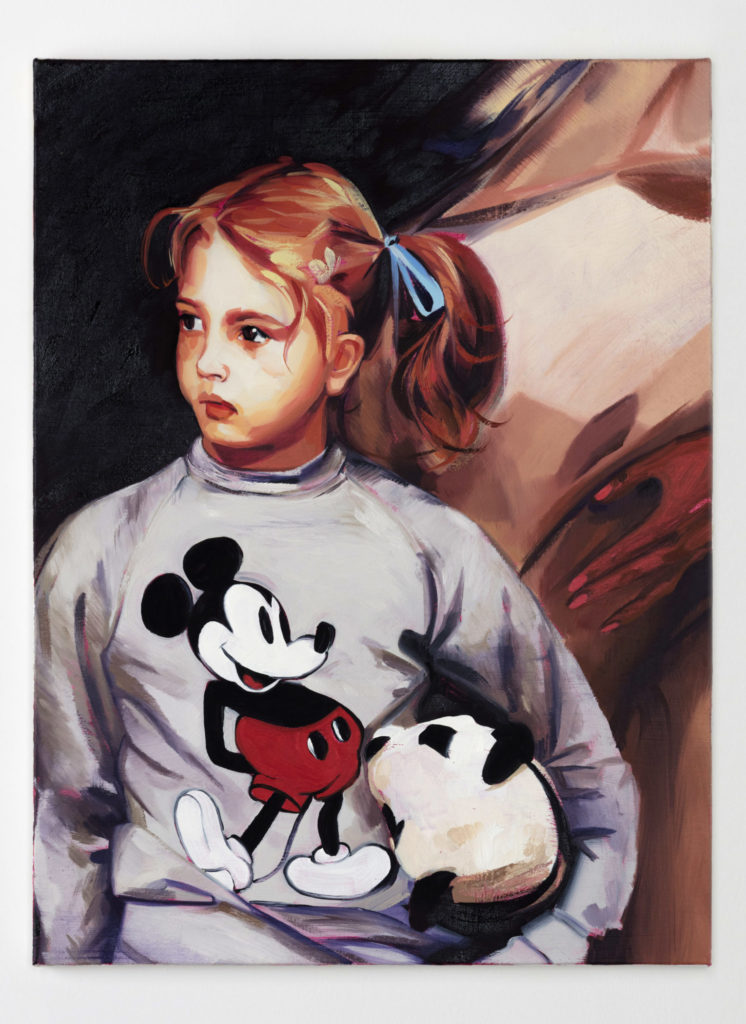

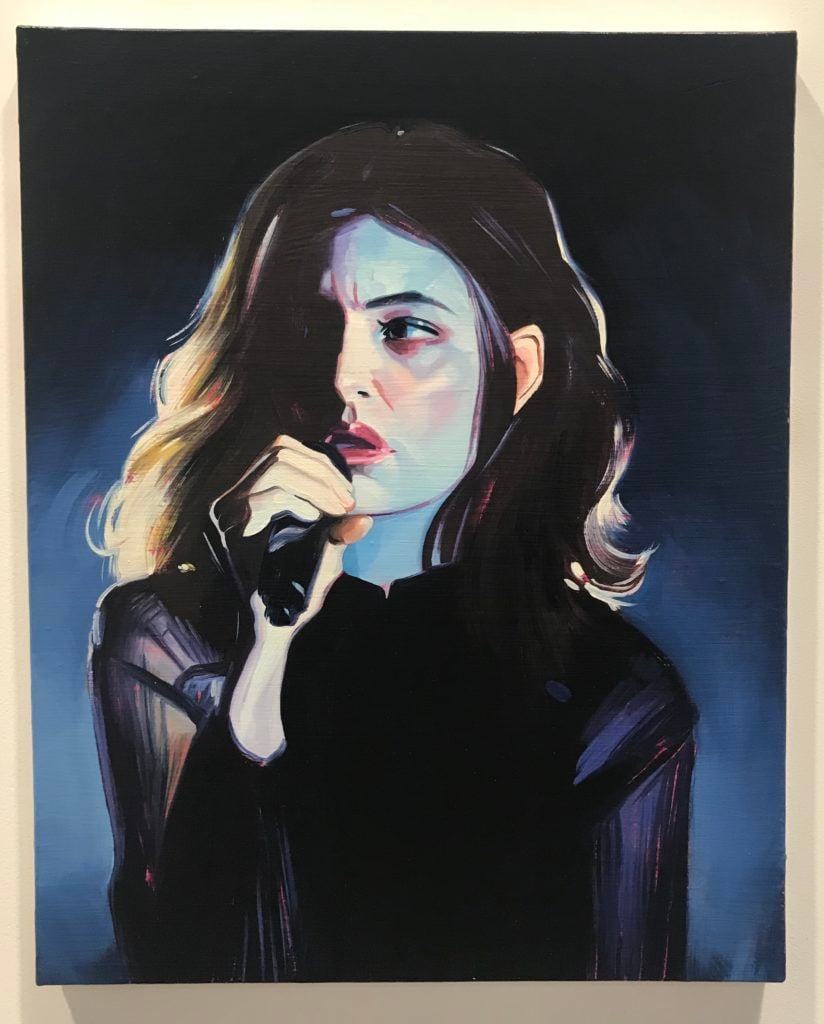

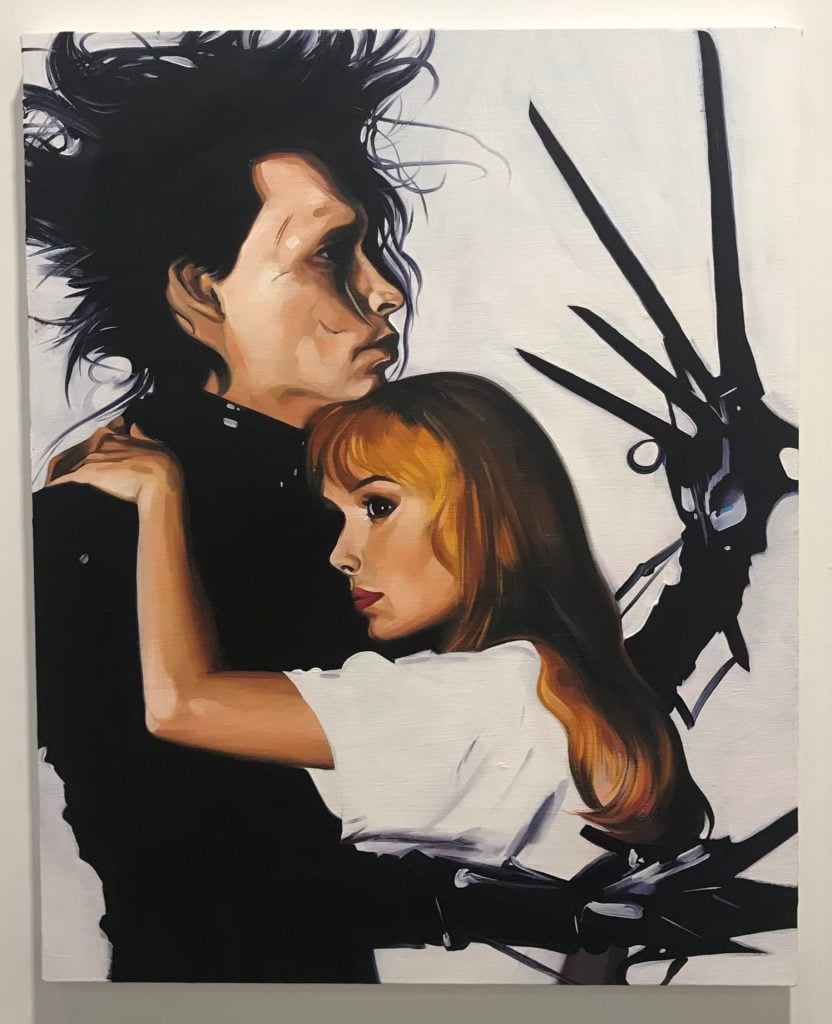

If the dealer had any gloomy thoughts about the market, none of it could was evidenced in his booth itself. A 1,000-square-foot stand that he had laid out to resemble a three-room brick-and-mortar gallery space, it was elegantly arrayed with a few dozen small to midsize paintings and drawings by the 31-year-old artist Sam McKinniss, all of them infectiously vivacious, brimming with pop-culture savvy, and with élan to spare. Intermixing portraits of celebrities with recreations of historic portraits and flower still-lifes by the 19th-century Parisian bon vivant Henri Fantin-Latour (who was known for painting the glittering figures of his own day), it amounted to a convincing act of aesthetic leveling, while at the same time showcasing some truly bravura painting. The colors glow; the impressionistically loose brushstrokes are lovely to look at one by one, while cohering into images of dorm-room-poster-worthy pop. It’s pure pleasure.

Freire first met McKinniss a few years ago after the artist Borna Sammak suggested he do a studio visit. Recognizing nascent talent, Freire told McKinniss, “Unfortunately, you have to keep painting every day for 14 hours a day if you want to be great.” He put the artist on a stipend so he wouldn’t be distracted by working odd jobs, and allowed McKinniss to “really push himself as a painter,” giving him his first solo show with the gallery at Team (bungalow) in Los Angeles in 2015.

The Lorde portrait at the fair.

These days, McKinniss is widely seen as an up-and-coming phenom, and collectors have been swarming the booth. By the second day of the fair, all but one painting had been sold (at $12,000 to $55,000 apiece), and both “diaristic” drawing grids had been snapped up for $45,000 each. His portraits—of such starry subjects as Rihanna, Anna Wintour, Lana Del Ray, and Rose McGowan (in her threesome scene from The Doom Generation)—had also won the notice of at least one of its celebs. Lorde, who previously commissioned McKinniss to paint an album cover after seeing a massive portrait he painted of Prince in Purple Rain, saw an image of the new painting he made of her Twitter profile photo and wrote the artist a note relaying how much she loved it. Too bad Freire had already sold it to a “very powerful collector,” the dealer said. The waiting list is about 100 people long, including museum trustees, so he’s only allowing each collector to have one painting—and Lorde already has one, since McKinniss gifted her the one gracing her album.

A number of other dealers came sniffing around as well, offering to give McKinniss shows, too. “What you do when that happens is you put them all in a bucket and sit down with the artist and talk them through on their individual merits,” Freire said. Does he worry about poaching? “The whole engulf-and-devour thing has never bothered me,” he said. “You have to say, ‘Here is my artist—come and take them.’ And if the artist leaves, they usually come to regret it, because the bigger galleries provide a different kind of services.”

As to the gallery’s own next steps, Freire is eager to embark on the new post-fair phase of his career. “The math is like this: a little less money will come in, but a lot less money will go out,” he said. “For us, we’re going to invest that money in publications and travel. And what we’re doing with the program is adding new energy to the gallery. No one knows what’s going to happen when people come in to see the Parker Ito show in May and find out that it’s a one-work show.”

Meanwhile, Freire is turning his attention to LA, where he had always intended his bungalow space to be a five-year project. Now that those five years are almost up and his program has expanded from one LA artist to five, he’s planning to open a bigger gallery in the city. “It’s not going to be a 20,000-square-foot space in a warehouse that looks like Mad Max lives there,” he said. “It’s going to be a 5,000-square-foot space. But I’ve wanted to have a real gallery in Los Angeles for 25 years, ever since I started Team. I think it’s a great city.”

See more artworks by Sam McKinniss from the fair below.