Kenny Schachter

Are the Basel Fairs Eating Each Other? Kenny Schachter Has a Theory—and News of a Big Bezos Art Deal

Fresh from Switzerland, our columnist also reports on the Digital Art Mile, which ran alongside the main event.

Fresh from Switzerland, our columnist also reports on the Digital Art Mile, which ran alongside the main event.

Kenny Schachter

Forget the pretense, let’s cut right to it. In a page from the Arnold Schwarzenegger handbook, a notable older art dealer was caught by his younger girlfriend with his housekeeper in flagrante delicto (Latin for “in blazing offense”), shining more than the silverware, I am told. And that was that.

Jeff Bezos, who could buy the entire art market in any given year and have enough spare change left over to erect a few more monuments to his manhood in the form of his reusable rockets, bought one of the approximately 22 extant Modigliani reclining nudes for $180 million from Christie’s, private treaty. The Modigliani was sold by off-the-radar (until now) New York-based Greek nonagenarian Sophie Coumantaros, who is perhaps tidying affairs for her four children.

The nudes formed the basis of Modigliani’s only solo show in his lifetime, in 1917, which was unceremoniously shut down by the police for indecency. To rub it in the face of the Parisian prudes at the time, one example had been hung in dealer Berthe Weill’s storefront window. Some things stubbornly never change: suffocating censorship and a little-known female dealer being much less known than her male counterparts.

Weill (1865–1951), by the way, was the first to sell paintings by Picasso and Matisse, and exhibit the works of André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Diego Rivera, Georges Braque, Kees van Dongen, Maurice Utrillo, Jean Metzinger, and many others. (Read more in Weill’s memoir, Pow! Right in the Eye! Thirty Years Behind the Scenes of Modern French Painting, which was published in 1933 and released in English by the University of Chicago Press in 2022.)

Idiots at Art Fairs Wearing Sunglasses, the title of my upcoming monograph. When will they ever learn? Art and the naked eye don’t need intermediaries! Photo by Kenny Schachter.

I know an elderly couple who have another one of the coveted Modigliani nudes hanging prominently and proudly in their living room. They are being assiduously courted by a few high-profile galleries, or rather, gluttonous predators with split personalities—close friends to many, until a potential deal brings out the devil.

There is a long history of artists fudging the dates of their works, saying they were made in years that fetch higher prices, from Picasso to an unnamed friend of mine (it might have been Donald Baechler) who sold me such a work. That was fine, until the actual year bled through the paint with the fictional date. Oops. On an altogether different level (as with everything he does) is Damien Hirst, who has been playing fast and loose on the dating of thousands of his artworks, according to my sources, from vitrines to spots, replicating with a velocity faster than Covid. (Hirst has defended his approach, saying that he dates works based on when he conceived them, not when they are executed.)

I can further reveal that a graphic designer who worked on Hirst’s catalogue raisonné was asked to Photoshop a dozen “1990s pieces” using parts of previous paintings, which were subsequently produced, signed with earlier dates, and included into the ‘90s section of the book. An inquiry to Joe Hage, Damien’s business manager and the most powerful unknown person in the art market, has gone unanswered.

Oh, right, and then there was Art Basel-Basel. As at most art fairs, you would have thought we had been teleported back to the 1950s, or hundreds of years before, given what was on offer—i.e. a lot of canvas. The art market remains as conservative as Lloyd’s of London, which was launched in 1652 along the banks of the Thames to insure British shipping routes.

John Armleder, 75, closed his gallery/performance space/bookstore in Geneva long ago—it lasted from the late 1960s to the mid-’70s—but his suitcase-sized booth in a corner of Art Basel lives on, an Art Basel stalwart. This year’s works were by Chuck Nanney, like Richard Tuttle on meth. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

While day one was relatively jammed during the much-hankered-after early entry period, the second VIP day was practically desolate. (In actuality, the “very important” part of that equation has been extinct for ages.) I was half-expecting tumbleweeds to roll down the desolate aisles. A large contingent of those missing in action were Americans.

What accounted for the dearth of people? A frequent refrain I heard from more than a few disgruntled dealers was that the Basels are beginning to feed off of themselves. That could get worse: In October, Art Basel Paris (goodbye, Paris+) will be staged at the Grand Palais for the first time, after the completion of renovations there.

The little city of Basel in the best of times has a chronic shortage of decent hotels and restaurants. During the fair, you get crummy, pornographically priced rooms and a lack of ancillary events (namely parties, which many pathetically prefer to partake in than the art). It looks like Paris will be the new Miami, and that it will probably devour that Basel as well, which is not exactly a bad thing.

In the new social, political, and economic world order we live in, art-fair congestion is no longer measured by the number of private planes (PJs, colloquially) that are massed at the local airport. There were probably no more than a handful this year. I have devised a new index to measure a given event’s success: the Uber Metric. On the way out of town—always my favorite time of Basel—my driver informed me that his business contracted by a third from last year, and his workaday was reduced by half.

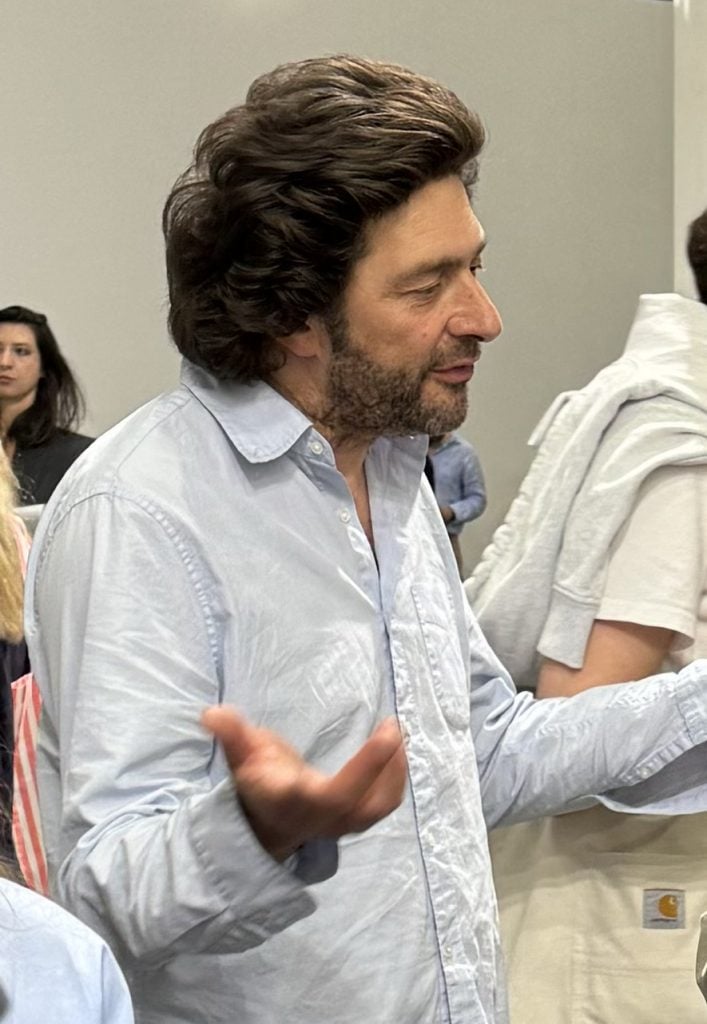

Philippe Ségalot, as famed for his art-advisory prowess as for the architectural marvel that is his hair, as seen at Basel. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

A New York dealer who recently celebrated decades in business told me, “We loved Art Unlimited and Art Parcours’ energy (large scale and site-specific sections, respectively), but we found the fair really boring and the list is too long to mention all the people who didn’t come, we sold, but just not a lot of energy!!”

Not to question the veracity of my friend, but precisely how much was transacted—despite various reports of robust sales on opening day—is among the greatest lies told after an individual’s earnings, drinks consumed per week, and age. The only people who love lies (and hyperbole) more than politicians are art dealers.

NFTs are like Brexit, I’ve decided. Like the ill-advised, self-sabotaging actions of the U.K., NFTs were nearly extinguished by the bald-faced crime and greed of the very “community” that created them. The malfeasance surpassed even that of the art market that the NFTers strove to emulate. Imagine that!

NFTs may still be dead (I haven’t given up, I’m afraid to say), but I will never tire of lecturing about them and now, add AI into the mix. For that matter, the Digital Art Mile was the highlight of Art Basel, so stuff that in your lap(top)! Photo by Kenny Schachter.

The bad news—for my predominantly art world audience—is that the widely held belief that NFTs are dead is at best premature, as evidenced by the Digital Art Mile, established by Georg Bak and Roger Haas, an alternative event held nearby Art Basel with a spirit all but lost to today’s ho-hum, cash-centric market mindset.

Basel should abandon the archly staid Murdoch method of focusing on money, money, money, and get with the program. (Scion James Murdoch is a major holder in Art Basel’s parent company, MCH Group.) We live in an era utterly obsessed with technology. Will the art world ever catch up? Does it even want to? If so, MCH should buy the Digital Art Mile, posthaste, and install it across the Basel board.

This is a fellowship you can be a part of without having to give up any of life’s forbidden pleasures, unless you are prone to buying too much AI or NFT art: Fellowship.xyz the standout booth at the first iteration of the Digital Art Mile. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

The standouts at the Digital Art Mile were Fellowship, an internet platform and roving gallery project specializing in AI-derived photography and accompanying NFTs, Robert Murphy’s RCM gallery from Paris, which focuses on digital art pioneers (the sector dates back to the 1950s, for those who bother to look), and the OG NFT market, MakersPlace, launched in 2016.

The equivalent of your grandparents remembering when hamburgers were 5 cents, I am old enough to recall a time when the only way to communicate artworks was by snail-mailing a plastic sleeve containing 20 tiny photographic slides that could be viewed by holding them up to a light. We couldn’t afford larger transparencies, which were considered extravagant at the time.

MakerPlace has been making markets in NFTs since 2016—about as OG as you get in the space. Here is Jessica Marinaro, its senior director and curator at the Digital Art Mile with a sold-out installation by artistic duo Operator. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

The paradigm shift of social media has utterly transformed the art world—and, unfortunately, our collective posture—like nothing I have seen in three-and-a-half decades in the biz. Only the blockchain compares, despite the dubious doubters. To paraphrase Artnet’s acting editor-in-chief, Naomi Rea, on the subject: People receive information about art today in a very different way than they used to, when independent magazines and newspapers were dominant. Without them, all that is left are influencers and a reductive popularity contest where value is conflated into the accumulation of likes and views.

The preceding sets the stage for me to announce my upcoming solo show at Galerie Nagel Draxler in Cologne, entitled “Phone Face.” It opens August 30 to coincide with DC Open, the Rhineland’s first gallery weekend, which is being jointly organized by galleries from Düsseldorf and Cologne. The title is based on the term “photo-face,” a term used to describe someone putting on a smile, etc. while posing in front of a camera. The concept is the effects that smartphones have had on artists, curators, museums, galleries, and critics alike; more so, the Insta-impact on the fundamental way in which art is experienced, communicated, and consumed—and how success in art (and, sadly, in life) has come to be measured.

We are increasingly defined by our phone-facing personas; in addition, Instagram has been nothing short of a historical shift in how art is seen, experienced and consumed. My upcoming solo at Nagel Draxler, opening August 30, will be a meditation on this phenomenon in all its glory (and horror). Photo by Kenny Schachter.

Putting aside algorithms and expurgation, the democratizing impact that social media has had by blurring geographic boundaries for participants while shifting hegemonies is mind-boggling. Granted, legacy hierarchies and barriers to entry remain, but others have been smashed. I can’t wait for what is to come, once we get past the stranglehold of existing platforms controlled by Zuckerfuck and erratic ol’ Musk-y. The trillion-dollar question is: What’s next? (We’re in a time where mere millions, not to mention billions, seem quaint.)

The current art climate is: What sells, sells (demure, aesthetically attractive or politically correct art), and what doesn’t, doesn’t (challenging, cerebral stuff), but more so. Setting aside Ezra Pound’s politics, he wrote: “Nothing written for pay is worth printing. Only what has been written against the market.” I would add that nothing made for money is worth making. As Duchamp said, “To live is to believe.” I will never stop believing in the omnipotent, ameliorative potency of art, despite the charades and shenanigans.