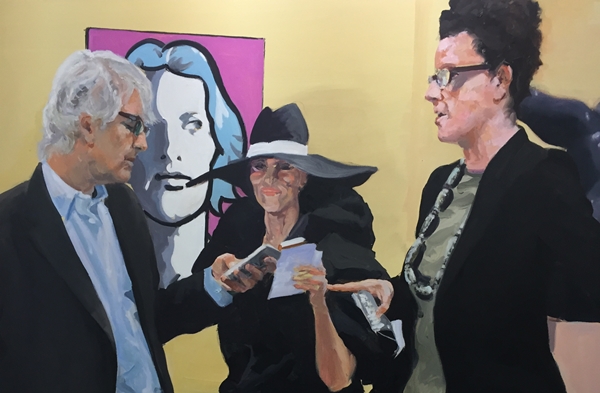

Eric Fischl.

Photo: Kenny Schachter.

Art Basel 2015 was a story both thrilling and catastrophic, ending with a real bang. Literally.

But before I get to that, and the fair, I made a quick stop in Zurich prior to going up to Basel to see some art and art people. Permit me a short digression to add context.

Visiting Zurich galleries with an up and coming young auction specialist, I heard tales about Twombly visiting the Vatican and comparing his own paintings to “chicken scratches in dust”—a fairly apt description.

At Ugo Rondinone’s show of large-scale painted faux brick walls the specialist was writing real-time auction catalogue notes aloud before the work was even launched in the primary market—seems like this guy was a good hire for the firm. Today art is readymade to be resold.

Still in Zurich, a London-based collector related a conversation at a dinner the preceding night. A seasoned collector and former bookmaker offered up some convincing advice to play the art market: “The way to win? Don’t make mistakes.”

The Basel frenzy and fair floor plan change was also a popular topic of discussion. Doris Ammann was up in arms due to a massive reconfiguration of the first floor galleries layout, and her displeasure of where she was “displaced” was demonstrable. The positioning of fair plots is as prized as billion-dollar chunks of Manhattan real estate.

A certain BIG gallery was not buying into the rejig, however. Gagosian was said to have thrown a strop, threatening to pull from the fair at the last minute rather than capitulate to the revised plan. It reminded me of a venerable New York collector that stayed with me in London and then refused to switch guest rooms when my parents showed up. Or the reaction of one of my kids when asked to do practically anything they don’t want to do: “No, no, no!”

Art Basel, what gives? When I queried Marc Spiegler, director of the fair, about the seismic geography shift he said: “Yes it’s more than a tweak,” and proceeded to show me a map with fully 61% of the galleries on the first floor, alone, relocated to new locations downstairs marked in red. Larry managed to stay put and hold his ground as did a few other powerful galleries whose proposed moves were reversed after Art Basel realized they were too big to put off.

You don’t f*ck with Gagosian, he’s bigger than Basel.

Sarah Lucas, The Last Crusade III (1993).

Photo: Kenny Schachter.

Checking out of my Zurich hotel, an old school European landmark and far better than the dumps that pass as hotels in Basel, I recognized a young European foundation owner (another cloak for art speculators to shield themselves in on the way to a profitable flip) accompanied by a tall sultry Russian speaking beauty fighting with hotel reception over a bottle of vodka someone had signed for at 4am.

The noticeably sweaty and anxious collector argued he was asleep in spite of his autograph on the receipt. Another player passed me exiting the lobby and said he was off to jail to return for the day. The art world wasn’t always so sleazy, mind you.

After a freeport visit where I literally had to hide from a friend viewing something of mine in another room with his client, I made my way to Basel where the bespoke Marxism of Okwui Enwezor’s Venice rallying cry was replaced by the strident call to spend. I checked into the Ramada, a stone’s throw from the entrance to the fair, a cross between a clinic and a dorm, for the price of the Plaza Hotel.

The tiny rooms fit like gloves and with no opening windows I nearly suffered an anxiety attack, but the lobby is crammed with bigwigs of all stripes, as there’s practically nowhere else to stay. When I spotted the Rubells and asked if they too were guests, Mera retorted they’d never pay the extortionate rates; they would prefer to stay in a hostel for 98.00 CHF and use the savings to buy more art.

If you set off a neutron bomb at the Ramada and the nearby Swiss Hotel during the fair, the art world would have an entirely different face.

Basel wouldn’t be the same without being snubbed for the umpteenth time by Klaus Biesenbach as he tunnel-visioned his attention to my friend of higher social standing as we passed each other in the street. Oh well, I am not Bjork.

The only necessary accessory for a fair besides a fully charged camera phone (they need a booth selling electricity) is plenty of mints. These are manic social gatherings with plenty of chitchat, so no use stinking as many do.

Getting into the door on the first of two VIP openings is like the jostling at a ’70s Who concert. Once in, hitting the floor running, it doesn’t take long before I have a series of sharp physical reactions in experiencing certain works of art, replete with erect hairs and goose bumps. The effect is often instantaneous, too.

This reminds me of the US Supreme Court definition of hardcore porn in the landmark 1964 case where Justice Potter Stewart said he couldn’t describe it in words, “but I know it when I see it.”

I saw plenty.

Christopher Wool, Untitled (2009).

Photo: Kenny Schachter.

Lets start with Christopher Wool. In a 2006 article I wrote entitled “Pulling the Wool,” I expressed uncertainty as to the longevity of Wool’s market and suggested following the advice he painted on a work sold for a then-record $1 million: “RUN”.

My wife still refuses let me forget my mistake on that front; $29 million later (the record his work “RIOT” recently fetched at auction), I’ve come around to my senses.

The new twisted steel sculptures of Wool are like spray paint frozen in air, they are sensational, and even at $2 million a pop, they are still utterly impossible to get a hold of according to Luhring Augustine, the primary dealer. Wool paintings were aplenty here, spotted at Van de Weghe Fine Art (two sold for $5.5 million and $1.75 million), Gagosian, Simon Lee, Richard Gray, and Dominique Lévy, among others. When an artist is hot, their works flock to market.

Art could be the only business where you can wander the aisles at a fair or in galleries and a few nods and handshakes later easily rack up a bill of $187,000,000 without ever exchanging a signature or even having the intent to pay up! Not that I’ve ever reneged on anything after a seemingly unavoidable impulse. Wink.

There is so much to like, it’s an easy way to end up in debtors’ prison, but then again there’s never really an actionable contract in the course of doing billions of dollars of sales.

Roth Bar & Studio. Dieter Roth, Björn Roth and Oddur Roth.

Photo: Kenny Schachter.

The painted bricks of Kelley Walker, for $400,000, and a $2.2 million self-portrait by Rudolf Stingel, both at Paula Cooper, sold swiftly.

At Jablonka Gallery there was a $1 million Warhol black-and-white penis portrait along with a $4 million Warhol shadow painting, a $3.7 million monochromatic grey Richter painting, and a $500,000 Eric Fischl painting of yet another art fair featuring art adviser Josh Baer. As much as I like Josh and value his post-auction reportage, I think I’d rather live with Warhol’s dick.

The news was not always great. There was a Sigmar Polke painting I only recently sold, on sale again for 50% more at Anthony Meier, the go-to gallery for all things Richter and Polke. When I asked the dealer for an opinion on a painted photograph by Richter at another booth the reply was that the work failed the primary rule for a work of art: it wasn’t beautiful. Hmm…

You can smell the speculation in the tremendous leap in the prices of Franz West where David Zwirner and others are charging upwards of $1 million for works that might have been half that only a short matter of months ago. But the price move is well deserved and probably overdue in my estimation. I’ve been a fan for decades.

Galerie Bärbel Grässlin had a baby blue West beauty on double hold (there should be a no hold mandate for fairs, it’s a pain and inappropriate) for €380,000 and within eyeshot at Gagosian another papier-mâché work for $650,000; an instance of a classic art arbitrage, and a reason so many are attracted to the wild ways of the market today.

When I had a booth in the Art Basel design fair some years ago, Brad Pitt rolled in, sprawled himself over a futuristic Zaha Hadid lounger and drawled: “What’s the ticket?” I find that a great way to extract pricing information, which in some instances is more difficult to ascertain than state secrets.

Speaking of star power, Leonardo DiCaprio travels with a posse of “advisors” like pilot fish feasting on the bacteria in sharks’ mouths.

Sadie Coles had new garishly painted stone sculptures by Ugo Rondinone snapped up in mere seconds for prices of just above $50,000 to under $150,000; a Rudolf Stingel painting subtle in silver and salmon for $1 million (immediately worth nearly twice that on the secondary market) and three extraordinary early 1993 self-portraits on tabloid newsprint by Sarah Lucas—the only works from the series that survived a storage fire in London a number of years ago—that sold for £175,000 to £200,000 each.

I had consigned a handful of pieces to a handful of booths during the fair—common practice that galleries frequently engage in with dealers and collectors to secure works to fill booths in an environment where it is increasingly harder to get first-rate material. As a freelance curator and dealer, it’s like entering Art Basel in an art-filled Trojan horse, the best of all worlds without having to fork over funds to participate in the fair.

Without fail, there are paintings you see reappearing at fair after fair, like a certain green Picasso (that might have been at Landau Fine Art) that has more frequent flier miles than Bill Clinton.

By the end of every day the excruciating foot pain is comparable to wading through broken glass; we fairgoers are like pilgrims who visit the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City walking on hands and knees as an act of faith. Buying at Art Basel, trekking the globe to see art, is the art world equivalent. I’m just reporting.

At night(s) there is the bar at the premier Three Kings hotel (or the Four Queens, as a friend calls it), the only game in town other than the bistro at the Kunsthalle. This year the Kings had a Dieter Roth bar installed (by Hauser and Wirth), which only served to create more of a desperate, chaotic fire hazard.

The deep discussions ranged from a dealer claiming to have been “cock-blocked” by an advisor on a painting transaction—bad luck but nice nomenclature—to a collector that pondered entering the fair in a burka to avoid unnecessary human interactions. And best of all was the dealer who goes to Basel without even entering the hall to see the fair. He just comes to buy (through proxies) and sell at dinners. WTF?

I wrapped up my Art Basel trip with visit to the Beyeler Museum to see what $300 million looks like nailed to a wall. Oh, sorry, I meant the stupendous Gauguin show encompassing a ridiculously broad array of works, including a self-portrait as a beer mug, a particular favorite. The paintings manage to be riotously colorful, muted and faint at the same time; the effects are otherworldly and unto themselves.

Back on the road, the taxi driver to the hotel immediately launched into a frantic rant that he was an artist (a pissed off one at that) and all Basel fair attendees were cynical blah-blahs and worse, none of which I could make out. What I could understand was that he was demented and I was scared.

With all the pharmaceutical companies in town, you’d think he’d grab some cheap medication. It was an encounter that foreshadowed another more frightening taxi occurrence to come, and I don’t mean the five dealers cutting ahead of me in a race to get to the airport.

Photo: Kenny Schachter.

In the taxi home from Heathrow, Thursday evening, I was in a near life altering accident: when I bent to put something into my suitcase on the floor the car came to a screeching halt from about 40 m.p.h. and I torpedoed into the metal frame of the folding chair opposite me.

The violence of the blunt force cut through to the bone ripping a two-inch mouth across my cheek, causing a hairline fracture in my face, and nearly severing a group of nerves.

While I was admittedly in a little bit of an hysterical state of panic afterwards, the driver proceeded to scream for the duration of the way through traffic en route to hospital reminding me that I wasn’t wearing my seat belt. I didn’t need to be reminded, looking at a piece of flesh in the blood soaked t-shirt I used to staunch more flowing blood. Maybe he should be an art dealer.

I never understood the notion of someone having a good eye, as I always felt two were necessitated in forming a proper judgment. But that day I came perilously close to losing one. Even worse, in my case, the emergency room doctor said half my mouth would be partially paralyzed on one side and I’d lose the ability to smile.

Taking into account looks and age, that is kind of my signature feature anyway. Ensuing three-hour surgery revealed my nerves still intact, and though half my face is still numb as I type, I am hopeful to crack (not the best word) another Cheshire grin—albeit in the guise of the art world’s very own Tony Montana.

Photo: Kenny Schachter.