I feel like a cockroach. Not exactly the bug (though that too), but rather like Kafka’s metamorphosed version. After a grueling (for the audiences mainly) 9 ½ lectures in 5 ½ weeks, I am ready to take on a one-person show on Broadway. In between all that talking was my third appearance at an Art Basel with Berlin’s Nagel Draxler gallery. Since I transformed into a full-time artist and teacher (as well as co-author of a book with art historian Noah Charney on NFTs, to be published next year by Rowman & Littlefield), I can barely bring myself to attend art fairs, which I once did to chase art-world intel as much as to see stuff, stealing information from the rich for the benefit of the aspiring rich. Though one of my key sources, Inigo Philbrick, remains incarcerated and will continue to be locked up for some years to come—he was the Deep in Deep Pockets, my amalgam of informants—but fear not, there’s plenty more to fill his bespoke suede shoes.

On the lecture circuit. If it’s Tuesday I must be at the University of Zurich Blockchain conference delivering a keynote. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I may be bit rusty, but I’m rarely, if ever, wrong. To kick things off, a source, let’s call them Cheap Pockets in line with a worldwide economic hiccup on the horizon, revealed a few tidbits from the last spate of spring auctions in New York—namely that Damien Hirst himself engineered the purchase of Happy Life Blossom at Sotheby’s, from his endless series (they always are) of cherry-blossom paintings, which sold for a whopping $5,609,900 against a $2 million to $3 million estimate. If Hirst didn’t buy back his own painting outright, I hear that he and his team most assuredly participated in the bidding. (Am I the only artist without a team?) Which makes all the more sense considering the works are fabricated by the stacks, and that many remain tucked away in his (vast) storage racks. A handful of Hirst’s significant older works passed at last week’s London sales, confirming a truer sense of his—at best—patchy market. (A request for comment on the Sotheby’s sale sent to Hirst’s company, Science, was not returned by press time.)

Although it’s a myth that fossil fuel derives from dinosaur remains, I can confirm that the seller of the Deinonychus antirrhopus of Jurassic Park fame at Christie’s May contemporary evening sale for $12,412,500 was former oil trader (and current art trader) Andy Hall in partnership with private dealer Nicolai Frahm. The skeleton, nicknamed Hector for some odd reason, had previously graced the home of Hall after having been bought by the pair for $1 million; not a bad return for an old set of bones. Which corroborates the notion that auction houses will sell a dirty pair of underwear in an art sale if the price warrants it. The problem with privatizing the sale of dinosaur remains is that it removes them from the labs of scientific researchers. The issue with selling them in art auctions is that it’s stupid.

Deinonychus Antirrhopus, Montana, USA. Photo: Christie’s Images Ltd.

Besides controlling access—who gets to show and who gets to buy—galleries have historically kept prices under control with slow, organic rises regardless of auction activity. That’s no longer the case, with recently acquired work wending its way into auctions in ever-shorter periods of time. As a result, the gulf between primary and secondary markets in some instances has become a schism. “Spec-u-lectors” (a term I coined in 2014) connotes that particular breed of art investors with an attention span that rivals fleas in relation to holding periods, and they are continuing to find ways to flout “non-resale” and “right of first refusal” agreements that are baked into most invoices.

An art collector who has never resold a work belongs in a vitrine in a natural history museum. It’s not uncommon for galleries to lie to their artists, something certain dealers of Harold Ancart and Dana Schutz have done in the past, saying that works were sold to fictitious buyers only to buy the pieces themselves and then resell at prices significantly higher than primary. A new twist on this model has been launched by a dealer who left a high-profile gallery (not willingly) and is now joining forces with galleries and artists to hold back pieces from exhibitions and immediately re-offer them at significantly escalated prices, divvying up the proceeds among them.

Oh, and Laurene Powell Jobs, Steve’s widow, has switched allegiance from Pace Gallery to Hauser & Wirth, which could only be the result of how much money she was previously charged—no small thing, considering her art budget of over a billion. (A request for comment sent to Jobs was not answered at press time.)

NFTism was over before it started, so I have to get a new tattoo. Community and empowerment was replaced by scams and cash-grabs. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Abracadabra, did you catch the great crypto currency disappearing act? The market didn’t contract, it all but evaporated, down 80 percent in less than eight months. Bitcoin may become as extinct as Hector the Deinonychus. Could the heated art market be next? Probably, as witnessed by the recent tepid, sputtering, thin-on-the-floor bidding in the London salesrooms of the major auction houses. Art, surely, is not impervious to a global economy characterized by inflation rising as quickly as the stock market is declining—with both currently at the worst levels in 50 years. A perfect portent of this was the Koons gazing ball that burst when a visitor smashed into it in at Pace’s booth shortly after the opening of Art Basel last month. Against this backdrop, art’s seemingly invincible bull run—especially for the historic prices fetched for young artists with no history—can’t persist detached from a dollop of macroeconomic reality-testing.

After the precipitous drop of Takashi Murakami’s NFTs, he publicly apologized. Then he proceeded to sell nearly 150 paintings based on those very NFT works at Gagosian. If he was really contrite, he should have considered air-dropping some ETH back into the wallets of his disconsolate holders. About that plummeting NFT market (which is putting it mildly), I could care less. I’ve been making videos and digital art for over 30 years and that won’t change no matter the extent or duration of the crash—I’ll just continue to do what I’ve always done. In a perverted way, I prefer this crackup, since it reveals who’s for real and who’s merely panning for nuggets. What would be ideal is an NFT market pegged to a stable, dollar-denominated crypto coin to avoid the violent currency fluctuations. How do you consistently price your art in the face of 80 percent market corrections? You just can’t.

So much lip service has been paid to art scams while there is considerably more crime during any given lunchtime at Goldman Sachs than the entire art world in a year. Crypto is another story, although it’s the people who are greedy and corrupt, not the decentralized networks of computers. Additionally, I have had my bank account hacked and been on the receiving end of a counterfeit €20 note dispensed from an ATM machine this summer. Last week saw an unusual smash-and-grab heist staged by four goofy-looking, comically flat-capped robbers at the Maastricht fair. Though it looked more like a farce than an actual crime, I was informed by an interested party at London’s Symbolic & Chase, the gallery hit by the theft, that it was indeed real—with a considerable amount of jewels snatched, and only partially recovered. Skullduggery in the art world usually occurs behind the curtains or in front of the auction podium—by way of manipulated bidding—so seeing it happen out in the wild was a change of pace.

But let’s go back to Basel, where a famous Russian TV presenter tried to pay for art at a friend of mine’s gallery in rubles— the only currency worth less than crypto at the moment. Which reminds me of something the 1950s-era NASCAR racer Junior Johnson said: “The best way to make a small fortune in racing is to start with a big one.” The same could be said today buying and selling art and NFTs. A dealer at PPOW, which was new to Basel’s ground floor, the fair’s premier selling real estate, mournfully related that: “Some things never change—everyone wants the same thing, no one take risks or chances. Our works are too good to sell.” This sentiment was further affirmed by London dealer Richard Nagy, purveyor of the world’s most extraordinary modernist works on paper: “You can count connoisseurs on two hands.” Maybe he’s being generous.

Racer Junior Johnson could have been an art market correspondent too! Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Speaking of strategic positioning and territorialism, my art was on the back outside wall of my gallery at the fair—and, like size, these things matter, as many outright missed my installation altogether. Don’t get me wrong, I am as grateful and appreciative as hell to Nagel Draxler for having the courage to continue to exhibit my work (considering… umm, who I am) in such a highfalutin context, but I feel like the namesake character in Thomas Mann’s short story Tonio Kröger, peering through the window of party he’d never be invited to—I was born on the outside where I shall remain. Kidding aside, please don’t be angry, Christian (Nagel). Exhibitor Andrew Kreps, not exactly known for his sensitiveness, described my placement as “deep coach behind the wing.” Most reassuring.

Deep coach, behind the wing, aka the back outside wall at Art Basel with Nagel Draxler, though I’m still thanking my lucky stars for the opportunity. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

A few more tidbits: more than 90 percent of the people at the fair exercised their volition to go maskless, spreading the gift of COVID to dealer Christophe van de Weghe, Regan Projects’ Sean Regan, Gagosian’s Andrew Fabricant, and collector Richard Chang, among many others. Gagosian, who’s booth was manned by a pair of guards (the new status symbols?) but not the dealer himself, who fled shortly after the opening, sold his Mark Grotjahn for $5 million despite gallery reports it went for $7.5 million. Also, Marc Glimcher of Pace spoke of robust sales, which may have been true for their primary works on offer—though I hear secondary sales, which included a $22 million Picasso and $14 million Joan Mitchell, did not fare as well. The art world has its own relationship to the truth, and it is not a particularly strong bond.

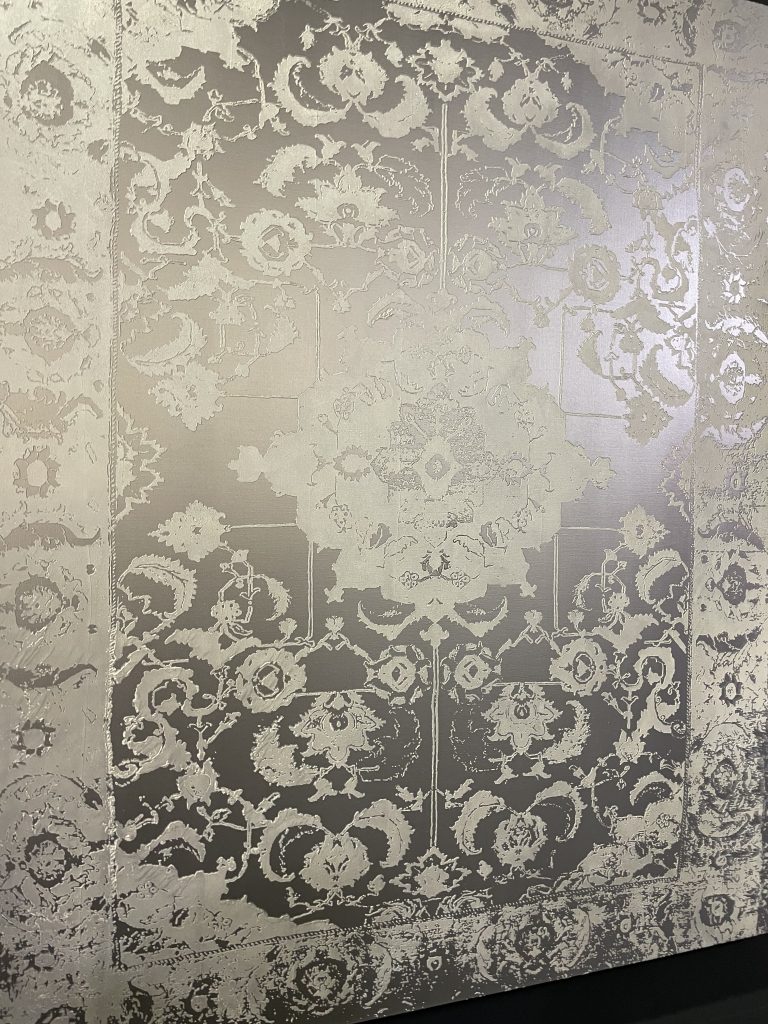

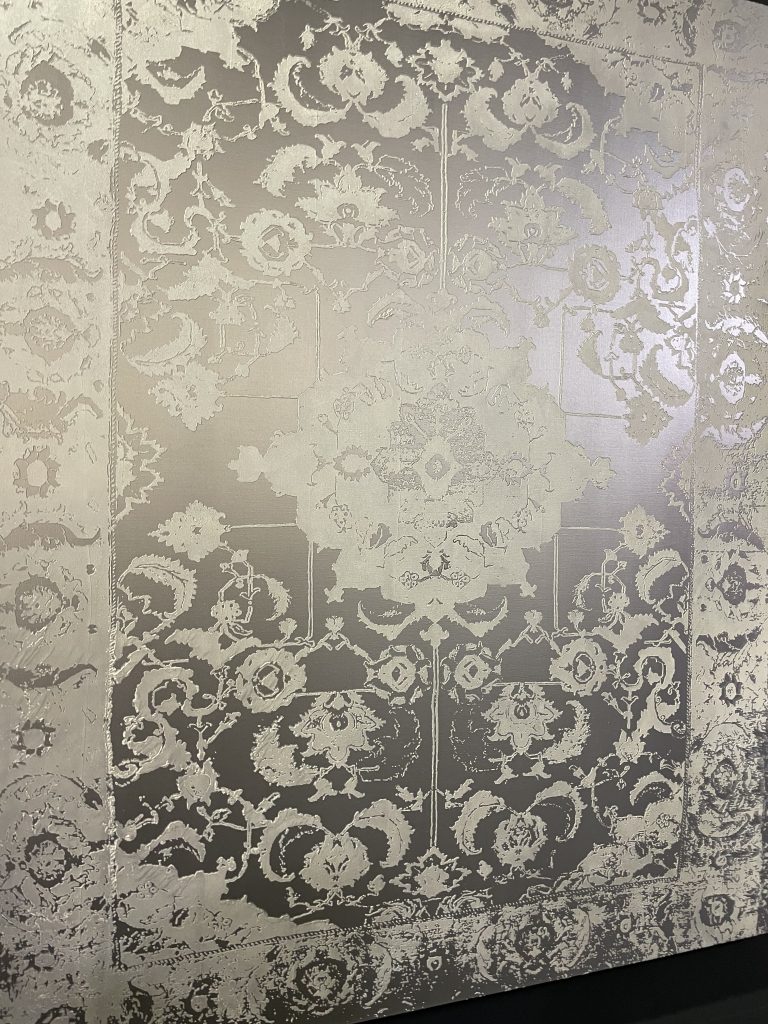

Going, going… not going anywhere. One of the many dead-on-arrival Rudolf Stingels, this one on hand at Luxembourg + Co., awaiting a certain Mr. Philbrick’s return from prison to relaunch the market. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The Rudolf Stingels, including the painting on view for $1.5 million at Luxembourg + Co (among other galleries), were dead on arrival—it very well could take the release of my ex-friend Inigo to resuscitate a market he once all but dominated (and manipulated). The Rudolf Stingels, including the painting on view for $1.5 million at Luxembourg + Co (among other galleries), were dead on arrival—it very well could take the release of my ex-friend Inigo to resuscitate a market he once all but dominated (and manipulated). (Paula Cooper Gallery senior partner Steve Henry begs to differ, saying they sold theirs on the fair’s opening day: “The Rudolf Stingel painting that we brought to Art Basel was a work that we could have sold multiple times.”) Throughout my days in Basel, I was forced to master the Muhammad Ali rope-a-dope to dodge enemies like the endlessly bitter, perennially ascot-clad, big-fish-in-a-small-pond Belgian Alain Servais, who infamously celebrated the lack of Americans at last year’s fair. Then there was the Berlin dealer who I overheard exclaiming to a well-known, private-museum-owning German collector: “No one will be at your funeral!” I never lose the joy of seeing how many ways Matthew Marks can divert his eyes in an effort to avoid saying hello to me after 35 years of knowing each other, or the latest sculptural iterations of Jordan Wolfson’s tormented relationship with his own Jewishness on view at multiple galleries. How could you not love the art world?

After graduating high school early, I worked on a farm in the chicken coop. When the birds reached a certain size, they were moved to the larger premises where I was stationed. Shifted via a small forklift, they would arrive, one load after the other, in modified milk crates that I was tasked with receiving and then shaking out the chickens into their new digs. The thing is that the chickens were so scared by the unfamiliar setting that they would huddle together so closely many of them would suffocate—or peck one another’s eyes out from fear—rather than spreading out into their new ample accommodations. It now seems to me not so different from the art and NFT worlds.

On the other hand, the most generous act on record throughout the fair proceedings was courtesy of Dusseldorf’s Sies + Höke Gallery, which complied with my request to put a Sigmar Polke from his masterful 1970s photo series shot in Pakistan and Afghanistan on hold for a whopping six months—probably wishful thinking on my part after I spent my mortgage money (and then some) on another Polke work on paper from 1978 from San Francisco’s Anthony Meier, a Cosima von Bonin sculpture from Berlin’s Galerie Neu, a Lynn Hershman Leeson self-portrait from New York’s Bridget Donahue Gallery, a Paul Thek pencil drawing from London’s Mayor Gallery, and a Zandile Tshabalala from my own dealer, Nagel Draxler.

A detail from Anthony Meier’s 1978 Sigmar Polke painting on paper from Basel that cost me my mortgage payment. Oops. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

You could literally walk through the fair without so much as shaking a hand, signing a contract, or bothering to take the escalator to the second floor and still manage to spend a billion dollars. Collecting art is not just a sickness but—especially in my case—nothing short of an incurable disease. Speaking of which, stay tuned for my Hoarder IV sale at Sotheby’s New York in December of this year, the latest installment in my series of no-reserve auctions.

A photo of Greek collector Dakis Joannou with his best, straight-grain Dunhill pipe, after he stuck it on a Coke bottle, sprayed it white, and continued smoking it—soon to be turned it into an NFT with me. Photo courtesy of Dakis Joannou.

What’s next? I have collaborated on a series of NFTs, to be released on NiftyGateway on July 7 with Dakis Joannou, the legendary Greek collector and art activist who established the DESTE Foundation in 1983. He’s a wildly adventurous octogenarian with a mind as open as the sea on which his Jeff Koons painted yacht floats. In September, I will participate in a group exhibit Kunsthalle Zürich curated by Daniel Baumann and Georg Bak, entitled “Snowcash,” a play on Neal Stephenson’s 1992 science fiction novel Snow Crash. In light of the topsy-turvy crypto market, the name might be better served as “Snowcashcrash.”

Taking in some real art by Donatello at the Palazzo Strozzi before my talk with Arturo Galinsino at the museum on the occasion of the book Let’s Get Digital, for which I was interviewed. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

An interview I did with the director of Florence’s Palazzo Strozzi, Arturo Galansino, has just been published on the occasion of the exhibition “Let’s Get Digital,” notable for the fact it’s directly beneath a once-in-a-lifetime Donatello show. Lastly, a new Taschen book is in final production, edited by digital art pioneer Robert Alice, featuring 100 OG (Original Gangster) NFT artists. Yes, it’s not lost on me how ridiculous that sounds, but it’s the accepted nomenclature of the crypto world; and, at my age, I am not about to start complaining about any opportunity that comes my way.