Market

Latin American Art: Breaking Boundaries for artnet

Roberto Matta was a great Chilean painter among Latin American modern artists.

Roberto Matta was a great Chilean painter among Latin American modern artists.

Christina Warner

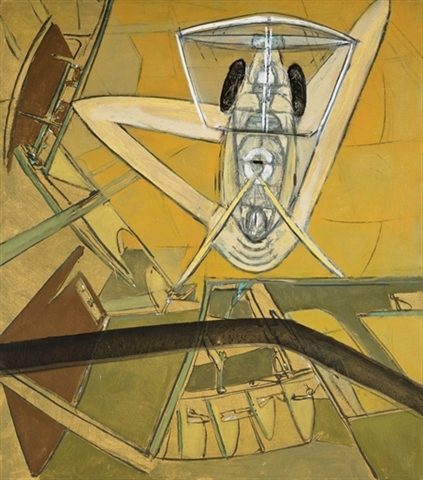

Roberto Matta, Le pendu (The hanged man), 1942

In today’s culture, the phrase “Modern Art” has been so misconstrued in its meaning, with such varying definitions that its original significance has been lost. At the core, Modern Art can be defined as a period from 1872 to approximately 1970, when artists were entrepreneurs of sorts, exploring with new styles, themes, and perspectives. This period gave birth to some of the greatest masters of Modern Art, such as Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973), Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), Wassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866–1944), Fernand Léger (French, 1881–1955), and Paul Gauguin (French, 1848–1903). Concurrently, this scope of experimentation in art expanded far beyond Europe to Latin America, where many countries and artists were strongly influenced by their European ancestry and culture.

One of the most internationally renowned artists of the 20th century was Roberto Matta (Chilean, 1911–2002), from Santiago, Chile. Matta was a recognized member of the Surrealist group, and one of the first Latin American artists to be part of the vanguard of the 1940s. He was one of the key figures of the art world who was completely immersed in all of the social and political issues of the time. Having lived in Paris and New York during the 1930s and 1940s, his Abstract compositions and naturalistic language clearly reflected the social tone and impact of the Second World War. It awakened a new awareness that broke away from abstraction and figuration, creating a nightmare scenario to his paintings. Matta landed in New York City in October of 1939, leaving France soon after it entered into World War II earlier that August. In Paris, his work was championed by André Breton (French, 1896–1966), who, by praising it publically in the May 1939 issue of the Surrealist journal Minotaure, solidified Matta’s reputation as an important member of a younger generation of Surrealist artists. Thus, soon after his arrival in New York, the Julien Levy Gallery, known for Surrealist exhibitions, invited Matta to show his paintings in 1940. The artist quickly gained a reputation and had a one-man show in 1942 at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, which received critical acclaim in the press. La révolte des contraires (1944) reveals a number of influences on the artist at that time. In 1941, he traveled to Mexico, where he became interested in pre-Columbian calendar systems. From 1942 to 1944, he met up frequently with Marcel Duchamp (French, 1887–1968) and the two extensively discussed their interests in mathematics and science. Matta was inspired by mathematical models he saw at Columbia University. The artist also studied magic, astrology, the tarot, and the occult writings of Eliphas Lévi. In La révolte des contraires, Matta created a cataclysmic space in a perpetual state of flux. Black curvilinear lines on a white ground suggest limitless space, as concentric circles spin, creating vortexes of energy. Flashes of exuberant yellow-green evoke an astral, otherworldly light illuminating the void. Illusionistic space is juxtaposed against opaque planes of black that emphasize the surface, and this vacillation (as the title indicates) creates a tension suggestive of processes of transformation. Simultaneously hermetic and accessible, La révolte des contraires depicts a metaphysical realm, where scientific notions of the cosmos meld with the interior, psychological space of the mind.

Roberto Matta, La révolte des contraires, 1944

Energetic and charismatic, Matta was able to translate European Surrealism to a generation of young American artists in a way that would galvanize them to experiment with its techniques. This ultimately encouraged a new phase of American Art: Abstract Expressionism. La révolte des contraires is a masterful example of Matta’s use of thin washes of pigment, undulating lines, and flame-like breakouts of prismatic color to portray a non-Euclidean space he dubbed “inscapes.”

Also during this period, the artist’s work took on a more socially conscious edge. Exploring the horrors of World War II, Matta began incorporating menacing, machine-like contraptions, with highly charged and strong color palettes offset by bold contrasting lines. A visual language, which the artist referred to as “psychological morphology,” aimed to convey the tension between figuration and abstraction. The artist’s works full of anguish and violence made use of the aesthetics of primitive art, placing humanoids on a surreal atmosphere derived from the subconscious. In the 1960s, Matta was elected by Chilean president Salvador Allende to be Chile’s cultural attaché, due to his continuous dedication to the political and social causes of Latin America. Throughout his life, Matta truly believed that art was a powerful agent for social and political change. Therefore, his revolutionary nature and style of painting with emotionally charged colors not only documented historical events, but altered the way Latin Americans viewed the world and themselves at the time.

Roberto Matta, Sans titre, 1947