Market

Scientist Albert-László Barabási on What the Data Says About the Changing Laws of Artistic Success

The famed network scientist has spent years studying what factors determine success in different creative realms.

The famed network scientist has spent years studying what factors determine success in different creative realms.

Artnet News

Some 20 years ago, Albert-László Barabási, alongside Réka Albert, coined the term “scale-free network,” showing how despite the belief that the internet put everyone on the same level, new forms of hierarchy were emerging within it.

More recently, the Romania-born scientist has turned his eye to the art world, making waves in 2018 as one of the authors of a study titled “Quantifying Reputation and Success in Art,” published in Science. Looking at the exhibition history of a half-million artists, Barabási and his co-authors argued that career prospects for artists were predicted by their connections to invisible networks of prestige.

Now, Barabási has put his mind to a realm that exists at the crossover between these two earlier interests, the web and art: the NFT scene. Last May, he published a piece in the New York Times looking at data from OpenSea to assess what determines success in the crypto-art space. The analysis showed, once again, that influence was extremely concentrated, with a few highly active NFT collectors dominating.

His paper “Quantifying NFT-Driven Networks in Crypto-Art,” published in February with Kishore Vasan and Milán Janosov, offers a wealth of insights into the dynamics of the NFT scene beneath the hype. This time, the data came from Foundation, an NFT platform notable for focusing on sales of original digital art, and for being an “open platform,” where artists invite new artists. This feature gave the authors the chance to study how networks of social influence function, and how, specifically, the profile of the person who invited you affects visibility and success within the space.

Albert-Laszlo Barabasi. Photo: Hamu és Gyémánt / Lábady István.

Recently, Barabási spoke to Artnet News’s Tim Schneider for the Art Angle podcast about the results. (Schneider also breaks down his insights in more detail in a piece for Artnet News Pro.) Below, we pull out some of the key highlights from the interview.

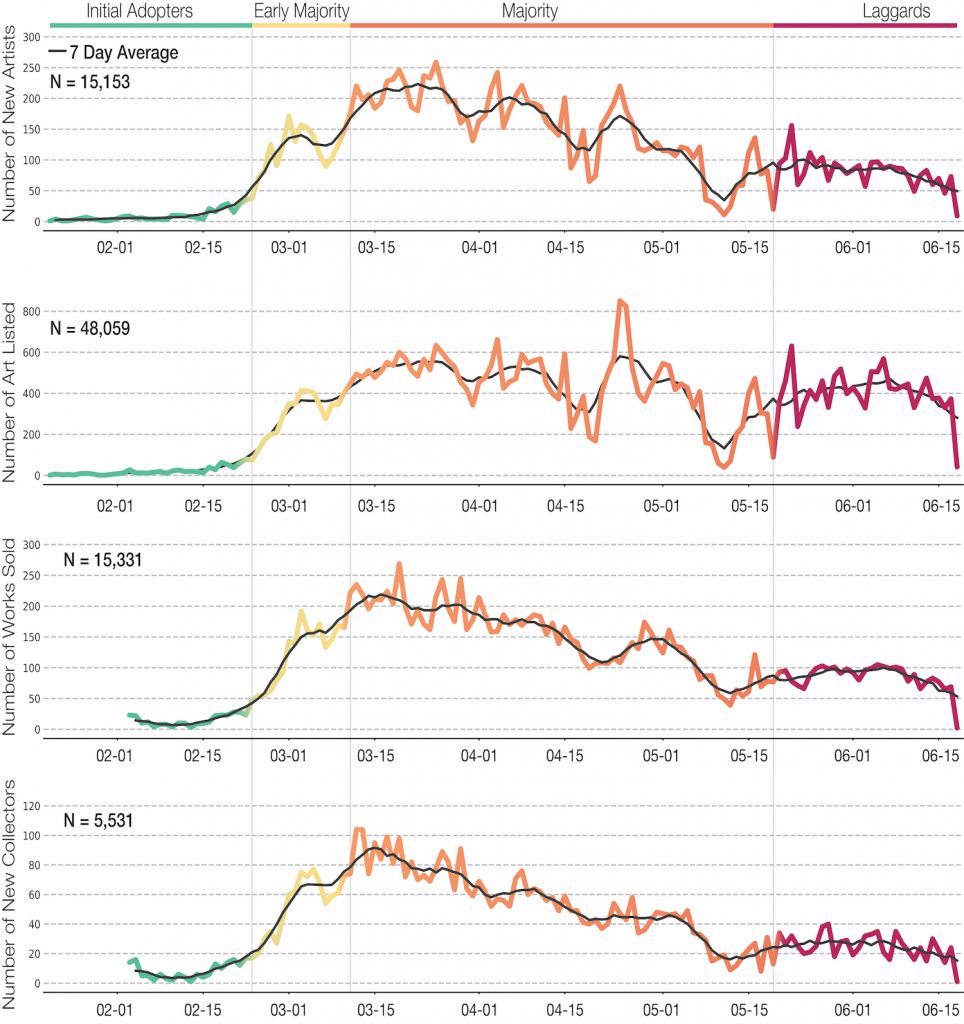

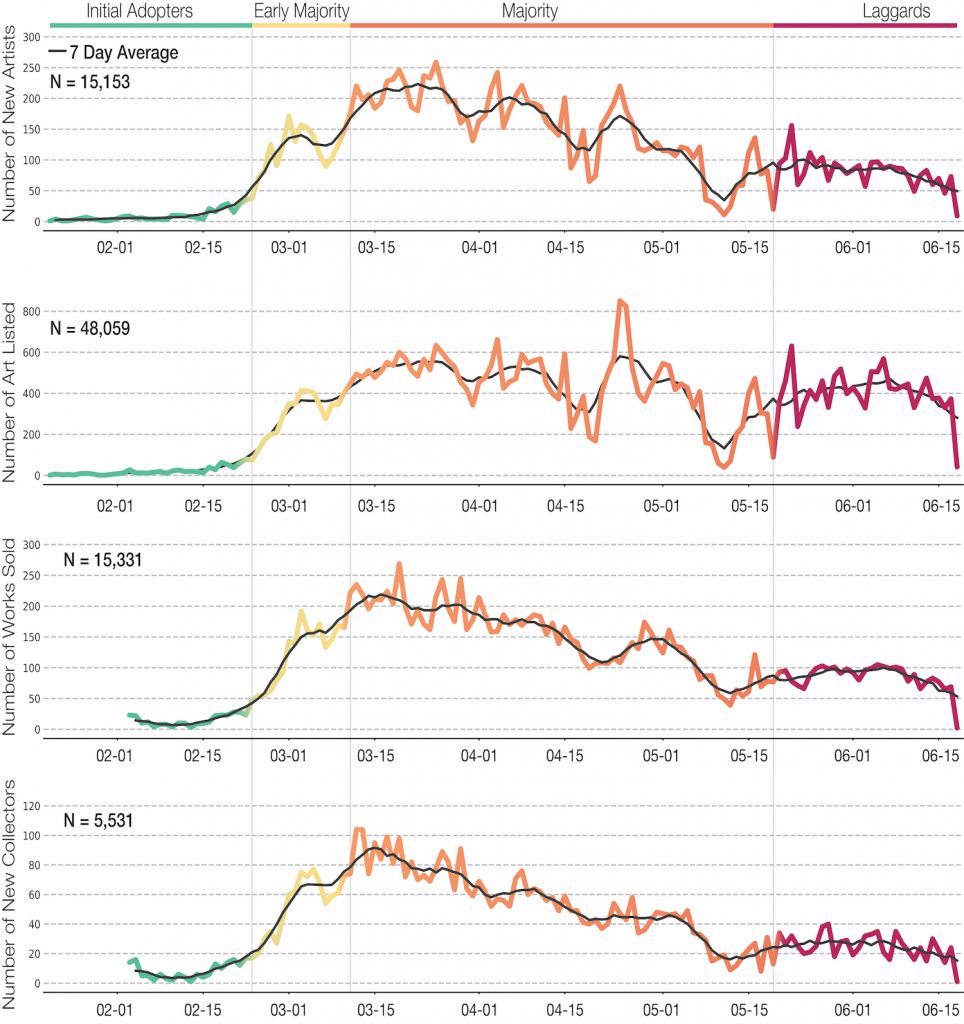

“At the end of March and early April [2021], there was an explosion. About 200 to 250 artists per day were joining the platform. That lasted most of April and then started to decay, and around May it reach what I would call a new ‘steady state.’ Foundation continues to attract new artists, new artworks, and sales, but no longer at the rate that was happening in March, partly because most artists who have interest in the NFT space successfully joined the platform in that early moment. When you look at the number of artists, or at how many works were put up for sale, or how many works were sold, you see a hat-like [graph]: you start out with the low numbers; it explodes in March and April; and then it goes back to a steady state that characterizes the platform even today.”

“Today’s well-known artists on the platform are typically those who joined early. There are exceptions—but the ‘first-mover advantage’ is hugely there, in terms of how much they can ask for their work, how much money they have accumulated, and the likelihood for their work to sell.

If you were among the early adopters of the platform, in the first few months virtually all of your work sold out. That has changed now. So what the new ‘steady state’ means is that, while at the early stages, maybe 20 percent of the work stayed unsold at any moment, now, 70 to 80 percent of the work is not finding any buyer. What happened is that the NFT art market became very, very similar to the classical art market, where we have a large number of artists who continue to produce work, but they have difficulty finding a collector to collect their work.

That doesn’t mean that works are not sold [on Foundation]. They sell quite a number of them and for quite a high prices—but there is this hierarchy of artists. Particularly for some of the early starters, they continue to put new work out and their work sells very fast. But the later arrivers have difficulty attracting bids and attracting collectors…. This doesn’t mean that you cannot get high values for your art now, if you are a later joiner. But now you have to distinguish yourself with the narrative or with some innovation that really gets you out of the pack—just like in the classical art market.”

“I really thought when interest is high, prices explode; when the interest is low, prices plummet. We know that in the classical art market prices are kept constant artificially by the galleries. But there are no galleries here, so it’s totally market driven. To our surprise, we found that despite these giant changes in number of sales and the number of new artists joining Foundation, there was virtually no change in the average price of the works sold or listed. The average price is somewhere between $1,000 and $10,000. There are minor fluctuations throughout these many months that we looked at, but there is no trend, no increasing or decreasing trend. It does not correlate at all with activity. So it seems like the way the market has naturally regulated itself is not by adjusting prices, but just by creating lots of unsold inventory.”

“When we started to look at the differences between these clusters [of artists connected on Foundation]… we saw that there are what we call ‘rich clusters’ and ‘poor clusters,’ which means that some clusters collect artists who consistently sell more for a very high prices and others collect artists who consistently sell for a low price. Which is kind of a reflection of real-word homophily, right? If you are a successful artist in New York with gallery representation and museum exhibits, you tend to hang around with other successful artists. So when it comes to inviting somebody to the platform, you will probably invite friends who are in the same category as you are.

However, if you are a struggling artist who has very few connections or connections to other artists who are trying to make it into the art world, most likely you will be invited or you will be inviting other artists who are in the same category you are.”

“To what degree does how many followers an artist has on Twitter really determine the prices of the work that he or she is selling? The answer is that there is a correlation—but it’s a weak one. There is a much, much stronger correlation between the number of Foundation followers—that is, to how many people follow you on Foundation—versus earnings. The difference is really huge. The Foundation followers are strongly predictive of how much you will earn; Twitter is just weakly predictive…

As a take-home message, what is important is that a new community has emerged within the platform itself, on Foundation, and that it is more important than the larger community that exists on Twitter.”

“The same narrative was there for the worldwide web early on as for the NFT space today—and it failed in the same way… When the worldwide web emerged 20 some years ago, everybody thought, ‘Finally, we have a medium where everybody’s voice could be heard.’ In principle, you can put your content out in the worldwide web and it will be immediately accessible to everyone.

But then, when you look at how many links are pointing to your content, suddenly the same ‘scale-free distribution’ emerged that we see in Twitter or on Foundation: The vast majority of webpages has one or two links to them, while a few, like Google and Facebook and so on, had billions of links pointing to them. So while the information that you put out is accessible to everyone, and very few people can find it because there are so few links pointing to you.

That’s what’s happening in the NFT space as well. While everybody’s work is being shown on the Foundation platform, and you have the right to put your stuff out if you are part of the community, for most artists, visibility is very limited. They have one, two, or maybe no followers. And so when they put out new work, no one notices.”

“It looks like there is no stability here when it comes to prices—the day’s flavor determines how much you will get for your work. But when we look deeper, we realize that this is not the case. For each artist, there is actually a window or a band of prices in which they move. And that band is very, very stable. It’s typically of the order-of-magnitude kind, and it’s very difficult for [an artist] to move out of that [range]. In other words, a notion of prestige has emerged in the NFT space, within the Foundation platform, and that determines the range of fluctuations you see. If you are in the low range of sales, selling for a few hundred, you will not see $100,000 for your work. You will typically stay in the few hundred [dollar] range…

What happens in the NFT space is very similar to the classical arts space, that there is artistic reputation that emerges through previous sales and through association with the community… Typically you can measure this in the classical arts space based on where you exhibit. Are you in MoMA or are you in an unknown museum? Or, what gallery represents you? In the NFT space, the only thing that we can use to measure reputation is price, as well as your likelihood of selling work. That’s what we do [in this study]: We’re using price as well as likelihood to sell work to establish whether you are a high-reputation artist or low-reputation artist. And what we are finding is that these types of reputation measures are very stable over time. That is, they really don’t fluctuate too much. Once you establish a reputation or a price range for your work, the community will continue to respect that.”

“With the [2018] study of classical artwork… we asked, ‘Are there examples of artists who really start low and make it high?’ And there are. We found about 250 artists who had that characteristic: They started in the bottom 10 or 20 percent and moved up in prestige to the top 10 or 20 percent…

We learned that what was characterizing them was early on a constant search—instead of staying with one gallery to represent them and show their work over and over, they really explored very widely, very early on exhibiting in different markets, in different types of venues, and so on. In this very feverish search, they hit across one or two spaces that had high enough reputation—typically unknown to them—to propel them into some degree of artistic stardom.

But for most of the artists, wherever they started, they actually kind of stayed there. Most high-profile artists that we have today on the market in the U.S. typically came up from Chicago or Yale, and they start high and they stay high. And that is why it’s so difficult to move up to the top, because the top is already busy managing these artists who started their career very high. Somebody who is starting from the bottom has to compete with them to find air, so that his or her work can be shown.”

“If you understand these mechanics, which is what we’re unveiling in the previous study and here, I really believe that you are in a much better position as an artist to really take advantage of these platforms—the NFT platform or the gallery system—and to succeed. In the same way that you cannot build a rocket without knowing Newton’s laws and taking advantage of them, you will not easily succeed unless you have either a natural sense or a detailed understanding of these forces that determine who is successful in this art space, be that the NFT or classical art world.”