Galleries

Sorry, We’re Closed: Dealers Explain the Painful Process of Shutting Down an Art Gallery

So you want to shut down your gallery. What happens next?

So you want to shut down your gallery. What happens next?

Eileen Kinsella &

Caroline Goldstein

First come the long, uncomfortable phone calls with artists. Then comes the packing of the inventory. Finally, you have to figure out what to do with all those boxes of archival material in your basement.

The process of closing an art gallery is as unique as the business of art dealing itself. In recent years, dozens of mid-size dealers have closed up shop amid rising rents, punishing art-fair schedules, and increased competition from mega-galleries. But when your business is all-consuming, what happens when you decide to shut it down?

artnet News surveyed a number of New York dealers who have changed course in recent years. Some of them have joined larger galleries, opened non-profit spaces, or begun to deal privately; others have left the art business altogether. What’s clear is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

The decision to close is “never taken easily, because when you are a gallery that sells emerging artists, that means you’re at least half an idealist,” says Jimi Dams, the founder of the Lower East Side gallery envoy enterprises, which announced plans to close last month. “In my case, I was 100 percent.”

For every dealer, however, one thing is clear: Closing a gallery is a much more significant life change than moving from one 9-to-5 job to another.

One reason shutting down can be difficult, gallerists note, is that the dealer is not the only one affected. The decision also disrupts the lives of artists, employees, and other associates.

“It is a full-on transition, and I find myself very fortunate to be able to afford and to choose to make the transition,” says Andrea Rosen, the longtime gallerist who announced that she would stop representing living artists in February to focus on managing the estate of Felix Gonzales-Torres. “While it goes through emotional stages for everybody involved, we all did our very best to try and wrap up projects with artists, and make sure everyone had time to plan.”

Andrea Rosen in 2010.

Photo ©Patrick McMullan.

After making the decision and notifying his artists, Dams entered into what he describes as the “third chapter”: “Where they all are asking to please not close because they have no other place to go.” Then, he began to send back inventory to the artists. “That also takes a very long time because of course some of the artists will stretch the process as long as possible in the hopes that maybe you will change your mind,” he says.

Dams understands this ordeal better than most. He got a crash course in unwinding a longstanding gallery in 2014, when his close friend Hudson, the founder of legendary New York space Feature Gallery, died. As his acting power of attorney, Dams helped shut down Feature before beginning the process himself. “Just to give you an idea, I have 275 boxes in my basement with archives and material that I need to go through now” left over from Feature Gallery, he says.

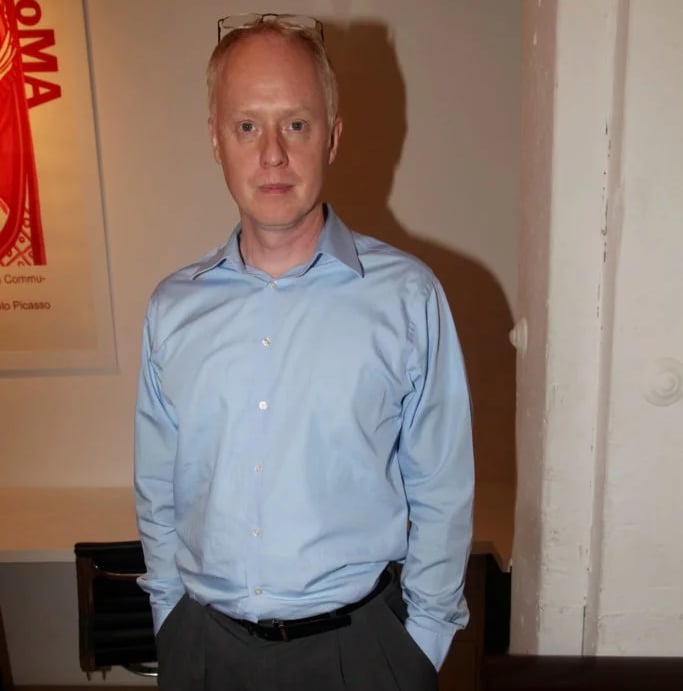

Mike Weiss, who closed his 13-year-old Chelsea gallery late last year due in part to the nightmare construction of a ten-story luxury condo next door, says an important part of the process is speaking to both artists and collectors about where they might go next. “We’re willing to get together, talk about the future, make recommendations,” he says. “I’ll help you with shows and if you need all the names of people who bought your work, we’re happy to provide.”

Mike Weiss. Courtesy Mike Weiss.

Melissa Bent closed Rivington Arms—considered among the first darlings of the Lower East Side scene—in 2009. She says that although most of her artists had European galleries at the time, she and her co-founder Mirabelle Marden worked with them to find the best fit for new representation in New York and Los Angeles. (Marden declined to comment except to say that the decision to close in 2009 was “personal.”)

In terms of logistics, Rosen is in a unique and remarkable position: Her entire gallery archive will be donated to and preserved by a major United States museum (the details of the gift are still in the works). Over the past five and a half months, a staff of archivists and freelancers have taken on the responsibility of helping to facilitate the move.

“The emotional pressure is eliminated—it takes the pressure of ‘what do I keep, or not keep’ off, but it’s an entirely new undertaking that entails a lot of work,” she says.

Many of the dealers we interviewed remain involved with art in their lives post-gallery, but are pleased to be spending time away from New York’s frenetic scene. The distance, some say, has allowed them to remember which parts of the art world they actually enjoy.

Joel Mesler, who transferred ownership of Feuer/Mesler to the gallery’s director last year, relaunched a previous independent venture, Rental Gallery, in East Hampton this summer.

Though he acknowledges that the space will be highly seasonal, he has been impressed with attendance in the first few months, telling artnet News he had better foot traffic on a recent Monday than on a typical Saturday on the Lower East Side. He also describes reconnecting with a nearby collecting couple who had bought a David Adamo work from him years ago before they stopped frequenting the Lower East Side.

Joel Mesler (center) with the artist Rashid Johnson and Gagosian’s Adam Cohen, courtesy of Joel Mesler.

Meanwhile, Zach Feuer, the other half of Feuer/Mesler, is out of the art dealing game altogether. He teaches students with special needs in an intentional community near Hudson. “There was no way I could continue to run a gallery with the enthusiasm and energy required for success,” he says. “I’m able to dedicate more time to political activities. I’m also more of a full-time dad, I bike a lot and I’m a volunteer fireman.”

Rosen, on the other hand, has not left New York City. Her new space—in the former home of Gallery 2, her second Chelsea location—will be focused on non-object-based art. It will have normal gallery hours open to the public, and some events are already in the works.

“Now more than ever, I’m committed to my inherent sense of responsibility. I’ve long lamented the notion of constantly shipping artworks, traveling for fairs—for environmental reasons,” she says, noting that her vision for the space reflects Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s ideas about the importance of non-object-based art. “For me, this is not an endpoint. The world is changing, and we have to respond and evolve…. I always have been and remain completely committed to the art world.”

David Shaw, Put Out (2016) at envoy enterprises. Courtesy David Shaw

Weiss, for his part, continues to sell art privately and launched an online gallery with his wife, artist Virginia Martinsen, called Gates of the West (after one of her favorite Clash songs).

“It was our way to get more involved with the artists… we felt like we couldn’t put this energy in before. I felt like collectors stopped wanting to go to studio visits, go out to dinner with the artists.” The new site has allowed the couple to “get back our sense of excitement.”

None of the individuals we spoke to expressed regret over their chosen career path. But several said they might have closed earlier if given the chance. “In retrospect, I stayed too long,” Mesler says. “When I decided to merge [with Feuer] and expand, the market was shifting at that exact moment.”

Asked what she would do differently, Bent—who was only 23 when she co-founded Rivington Arms and is now running a project space in Marfa, Texas—says: “I would have bought more art.” (Her former roster included the current art stars Jordan Wolfson and Dan Colen, who she showed just out of art school.)

Melissa Bent left the NYC art world for (literally) greener pastures, photographed here at Cibolo Creek outside of Marfa, TX by her husband, the artist, Michael Phelan.

Ed Winkleman, who closed his storefront in Chelsea three years ago but continues to sell art privately and co-produce the Moving Image art fairs, says he would have spent money differently. He advises young dealers to resist the pressure to invest in expensive installation build-outs and elaborate afterparties in favor of catalogs that will serve as a lasting document of what artists are really doing.

He also advises young dealers to be flexible. “Finding a niche is great when it plays to your strengths, but artificially sticking to a particular vision—out of stubbornness or some sense that that’s what you’re supposed to do—is a luxury given how quickly things evolve.”

Edward Winkleman. ©Patrick McMullan.

Photo: Dustin Wayne Harris, Patrick

Feuer has developed his own list of dos and don’ts: “Artforum ads are a waste of money. Call people back. Respond to emails. Keep your overhead as low as humanly possible and don’t spend money to try and impress anyone. Try not to be an asshole if you get a tiny bit of success (I found that difficult).”

Adam Sheffer, a partner at Cheim & Read Gallery and president of the Art Dealers Association of America, notes that “each gallery is a unique business with its own set of strengths and challenges and people make very personal decisions why they want to close. This is not an epidemic—it’s growing pains.”

For some, however, the only way to grow is to break away from the traditional gallery business. Jimi Dams, who plans to convert his gallery space into a foundation dedicated to the late dealer Hudson, says: “It’s a privilege to be able to say, ‘When it stops being fun, I’ll stop going to that job.’ You only live once. You don’t like your job, change it. And so that’s what I did.”