Artnet News Pro

What Can a Major Museum Show of Lucian Freud Tell Us About His Market? As It Turns Out, Quite a Lot

We took the National Gallery’s centenary tribute to Freud as a prompt for a market deep dive.

We took the National Gallery’s centenary tribute to Freud as a prompt for a market deep dive.

Colin Gleadell

London’s National Gallery recently opened “New Perspectives,” its centenary tribute to Lucian Freud, who was described by Robert Hughes in 1987 as “the world’s greatest living realist painter”—and was, for a while, the world’s most expensive living painter, too. Christie’s sold his fleshy portrait of Sue Tilly, Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995), for $33.6 million to Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich in 2008.

That work, however, is not included in the exhibition (was its Russian ownership an issue?). Nor, more significantly for the current market, is Large Interior W11 (after Watteau) (1981–83), no. 31 in the museum’s pre-printed catalogue. This rare early group portrait, considered a masterpiece, set a record $5.8 million when it sold at Sotheby’s New York in 1998 to Microsoft co-founder, and Imp-Mod trophy hunter Paul G. Allen.

Instead of hanging in the National Gallery, as the catalogue suggests it was intended to, the work will be previewed at Christie’s London during Frieze Week with a record-busting estimate of $75 million, which the house hopes to achieve when the Allen collection is sold in New York this fall.

Lucian Freud, Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau) (1981-1983). Courtesy Christie’s Images Ltd. 2022.

The piece set to break the record is quite unlike the discontented intimate work that was Freud’s most expensive while alive. “Allen didn’t really like nudes,” said dealer Pilar Ordovas, who took the Benefits Supervisor consignment for Christie’s before setting up on her own in 2015.

The sale of Large Interior is a significant moment—because Freud painted so slowly, his best works appear infrequently at auction. Over the past decade, total annual auction sales for the artist have been as low as $1.6 million (in 2020) to as high as $101.8 million (in 2015, the year of the Benefits Supervisor sale); most years have been in the $20 million-to-$30 million range.

The last significant painting to hit the block was the 2003 Portrait of David Hockney that is in the National Gallery show, which sold for £16 million ($20.6 million) at Sotheby’s London in June 2021—a record for a small portrait—to the U.K.-based Reuben family.

Whether or not Allen’s work will make its high price remains to be seen. “Nothing has sold privately for that much,” said Ordovas—an observation backed up by William Acquavella, the dealer who discovered Freud in 1992 and is one of the leading voices in his market to date. The top price for Freud privately is currently about $40 million, Acquavella noted, so if the work meets its estimate, as he suspects it will, it will present a whole new frontier for Freud’s market ahead.

But the potentially record-setting sale this season will inevitably prompt renewed interest in a range of works by Freud, including those that are included in the landmark exhibition at the National Gallery. The show’s catalogue provides vital intel on where these works have been and who owns them today, serving as a guide to Freud’s top collectors.

Below, we zero in on the most notable works included in the show, and the story they tell about Freud’s evolving market.

Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon (Unfinished) (1956-7). Lent by Ananda Foundation N.V. ©The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images.

All these eight-figure prices are a long way off Freud’s experiences as a young, unfashionable painter of Old Masterly, linear, graphic figuration. Although he liked to mix with the aristocracy and counted figures like Lady Jane Willoughby (a maid of honor at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953), the Duke of Devonshire, Lord Lampton, and Baron Thyssen among his clients, he made his own way, and didn’t really have a dealer until he signed up with Marlborough Fine Art (which represented him between 1958 and 1972), where he was handled by James Kirkman, who continued to manage his sales until William Acquavella discovered him in 1992.

Going back, he made some early sales to Tate and MoMA, but “In those days he was a pauper,” his biographer William Feaver said.

Freud’s early works (up to the late ‘50s when he switched from drawings and watercolors to oils with a new sable brush) are still considered more appropriate for local Modern British art sales at the auctions than postwar and contemporary.

But the market for early works has changed, reflected in the exhibition by an unfinished painting of Francis Bacon from the 1950s, which sold at Christie’s in 2008 for a low estimate £5.4 million. The lender to the exhibition is named as the Ananda Foundation, which, appropriately, because of the focus on Bacon’s forehead, specializes in neurological research.

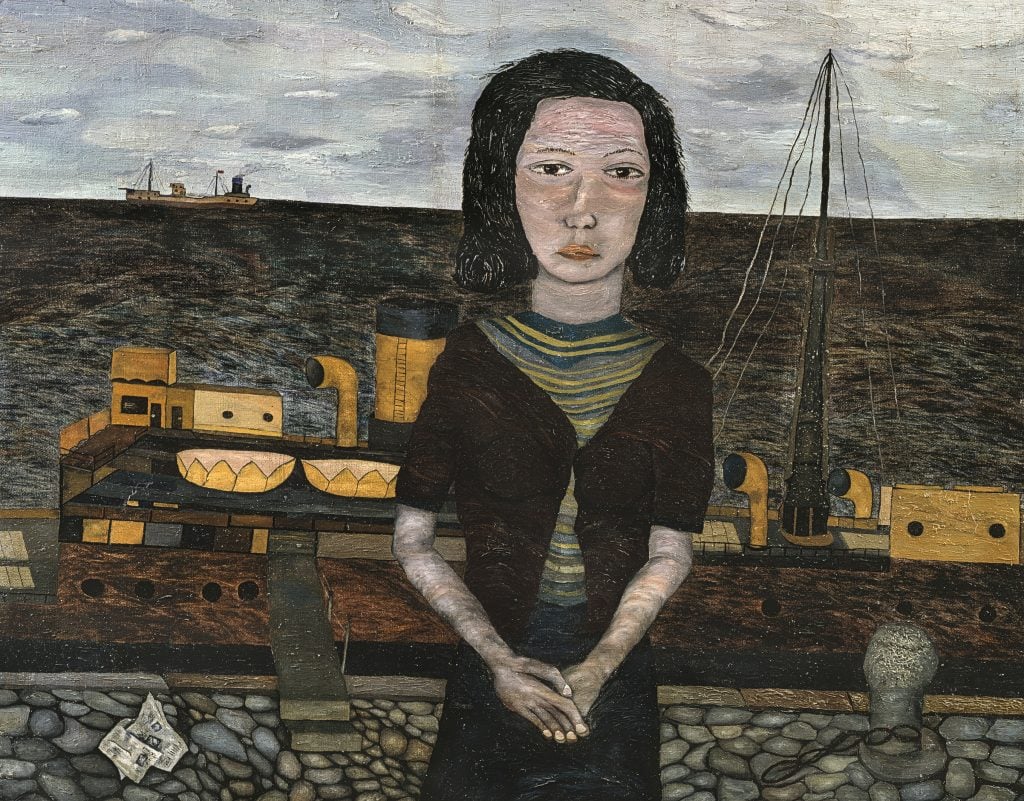

Lucian Freud, Girl on a Quay (1941). Rosemaur Collection, Melbourne, Australia, Courtesy Richard Nagy Ltd., London. ©The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images.

While the artist was represented by James Kirkman, his market had been primarily British. The London branch of Marlborough run by partners Gilbert Lloyd and David Somerset had a strong suit of British artists including Barbara Hepworth, Frank Auerbach and Lynn Chadwick, as well as Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, whose markets they were trying to internationalize.

The show includes Man with Feather (Self-Portrait), an oil of 1943, sold by James Kirkman at Sotheby’s in 2005 for £3.7 million—a record for an early work at the time. Further down the price scale is The Painter’s Room (1944), which sold in 1994 at Sotheby’s for £507,500, and Girl on Quay (1941) which sold at Christie’s in 2006 to dealer Richard Nagy bidding for Australian, Lindsey Hogg (the Rosemaur Collection), in 2006 for a low estimate of £400,000.

Not in the exhibition is Boats, Connemara (1948), a watercolor which sold for a double estimate £657,250 at Sotheby’s in 2012 to dealer Stephen Ongpin, bidding, it was believed but not confirmed for Met trustee, Leon Black, who was a client. Nor are there any works on paper that were owned by Kay Saatchi (ex wife of Charles) who sold them in 2011.

While Tate was a collector in the early days, the institution cooled off when prices began to rise after Freud’s arrangement with Marlborough and Kirkman (often in partnership then with Antony d’Offay). The museum is still represented as a lender of several works, which it acquired from the supermarket heir, Simon Sainsbury, after his death in 2006.

Lucian Freud, Painter Working, Reflection (1993). The Newhouse Collection. ©The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images.

Pilar Ordovas, who was assigned the role of personal contact with the artist at Christie’s before she acted as a consultant to Gagosian and then opened her own gallery in 2015, said the move to Acquavella in 1992, after Freud fell out with Kirkman and transferred his allegiance, marked a “big shift” in Freud’s market.

Acquavella swiftly broke into the U.S .market with an exhibition and sale to the Hirshhorn Museum, the first U.S. museum to show Freud in 1987, followed by the Met. Paintings in the National Gallery show which he sold to the U.S. include the standing self-portrait nude, Painter Working Reflection (1993), which he sold to Si Newhouse, and Nude with Leg up (1992), a portrait of Leigh Bowery, which went to the Hirshhorn.

Acquavella told Artnet News that he also broke into the Asian and Middle Eastern market, and recalled taking Freud’s primary market prices up a notch, selling large paintings of Leigh Bowery in the low millions of dollars.

Several works in this show are lent by Joseph Lewis, the Bahamas-based British businessman who must be counted as another important Freud collector buying in the 1990s.

In 1999 Lewis bought a large 1993 painting of Sue Tilley, Evening in the Studio at auction for $2.4 million, which looked cheap after Benefits Supervisor was sold. Acquavella also sold Lewis another portrait of Tilley, which is in the show Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, in 1996. Acquavella has also been active in the secondary market selling Lewis Naked Child Laughing (1963) in the NG show, privately in 1996.

Lucian Freud, The Brigadier (2003-4). Private collection. ©The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022/ Bridgeman Images.

As evidence of the long-term growth and shifts in his market is the painting Pregnant Girl, (1960/61), the mother of Freud’s first child, Bella. The painting first sold at auction in 1983, while his market was in the doldrums, for £44,000 to Kirkman, who then sold it privately to the British collectors, Ian and Mercedes Soutzker who put it into Sotheby’s in 2016 where it received competition from Russia and Asia before selling for £16 million, the fifth highest price for the artist.

But the highest public price paid for a work in the show is the $34.5 million paid at Christie’s in 2015 for the seven-foot portrait The Brigadier (2003), who is Andrew Parker Bowles (father of Camilla, the Queen Consort) in full military regalia. Parker Bowles never owned it, stating: “I couldn’t afford the millions it would cost,” and it was sold to the U.S. investment banker, Damon Mezzacapa. It was sent to auction after Mezzacapa died, where the buyer was not identified.

The centenary celebrations of the painter’s legacy are likely to prompt renewed market interest in the artist’s work. However, nothing quite moves a market like a flashy new auction record so if, as Freud’s dealers past and present suspect it will, the Allen painting meets its $75 million estimate, blowing past the $40 million high ever achieved privately, it will move the benchmark for Freud and open up new portals for his market in the next 100 years.