The Art Detective

The Macklowe Collection Is Back for an Encore at Sotheby’s in May. Can the $200 Million Trove Ignite the Same Fireworks?

The first sale of the epic collection assembled by Linda and Harry Macklowe delivered more than $675 million.

The first sale of the epic collection assembled by Linda and Harry Macklowe delivered more than $675 million.

Katya Kazakina

The Art Detective is a weekly column by Katya Kazakina for Artnet News Pro that lifts the curtain on what’s really going on in the art market.

Get ready for Act II of the Macklowe auction drama. Following the white-glove sale in November, Sotheby’s just unveiled the next batch from the collection of octogenarian divorcees Linda and Harry Macklowe.

The coming 30 lots are estimated to reap another $200 million in May, a sum that seems almost modest compared with the $676.1 million bonanza in Act I. Among the new offerings are a darkly sublime Rothko, Warhol’s camouflage self-portrait, a couple of De Koonings, and a monumental Richter seascape.

“The entire group is such a statement on classic modernism, on the history of the abstraction, the dialogue between abstraction and figuration,” said Brooke Lampley, Sotheby’s chairman and worldwide head of sales for Global Fine Art. “There are great, great opportunities for connoisseurs at every price level here.”

The second part has one obvious challenge—it comes second. Much of the Macklowe excitement is built into the market at this point, the story feels familiar, the auction’s success almost preordained.

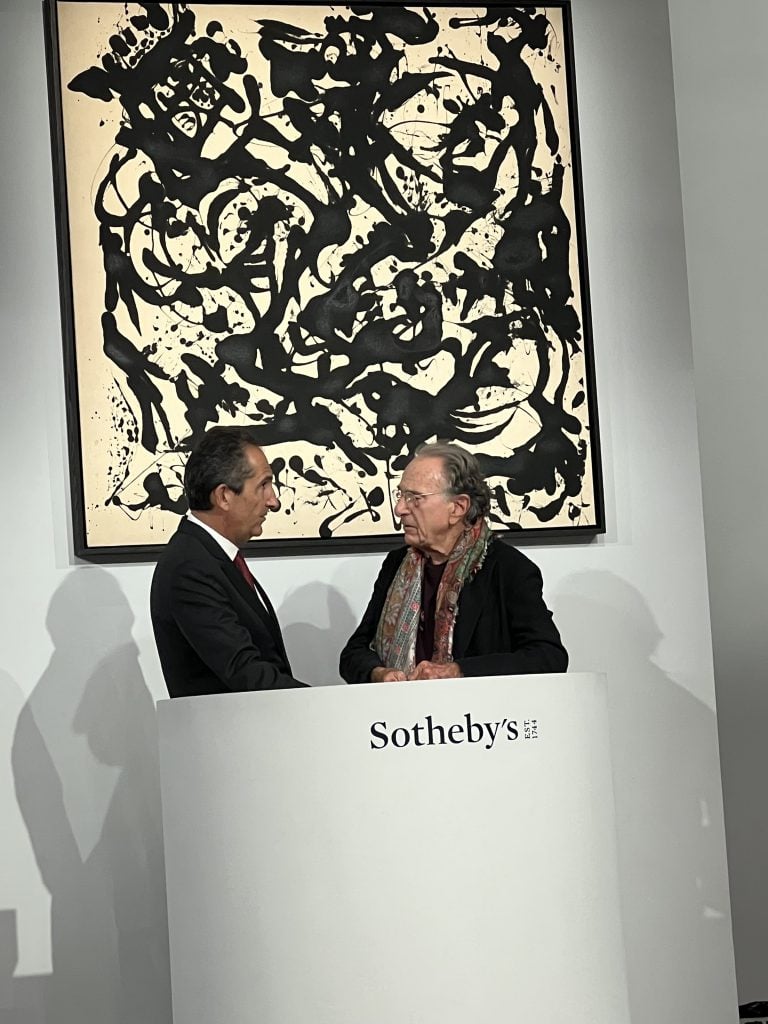

Sotheby’s billionaire owner Patrick Drahi and Harry Macklowe at the first sale, standing in front of Jackson Pollock’s Number 17, 1951. Photo: Katya Kazakina

To keep things fresh, Sotheby’s is leaning into marketing. Unlike the last time, it’s unveiling the lots in London, not New York. It also tapped Barbican Center’s artistic director Will Gompertz and curator Eleanor Nairne—not Sotheby’s specialists and executives—to present the works before they head to Asia, with stopovers in Hong Kong and Taipei. Nairne has curated exhibitions on Basquiat, Dubuffet and Krasner. Gompertz is an experienced TV presenter and the first arts editor at BBC News. Their lively, passionate 22-minute conversation amounted to a blitz art history lesson on postwar art.

Sotheby’s Macklowe 2.0 launch is timed to coincide with the previews of its mid-season auctions in London. Meanwhile, the stateside art world may be distracted with all eyes on Los Angeles this week, where Frieze L.A. opened for the first time since the pandemic.

“This is a collection of international importance, so getting it to Europe and Asia was a priority regardless of the art world calendar, fairs and such,” Lampley said. “We find it most effective to have works for a discreet viewing time and a particular place, often with an event or a cocktail to invite people. And then keep moving.”

Mark Rothko, Untitled (1960). Photo: Sotheby’s.

The Macklowe collection had been hotly anticipated by the market for years while the former spouses duked it out in court and the global pandemic further delayed the auction. The sale was ordered by a judge because the pair was unable to agree on how else to split their assets.

The works will be offered on May 16 in New York. Sotheby’s decided to split up the collection to avoid flooding the market with too many major works by the same artists all at once. And while the company promotes the idea that both parts are equal, offerings by the top artists have significantly lower values in the second group.

Sotheby’s won the trove, in large part, by offering a higher guarantee than Christie’s and so it sold off the most expensive works before the first auction through irrevocable bids to minimize its risk. It’s now accepting offers from investors again, Lampley said.

Declining to say which lots, if any, have been already backed by third parties, she added: “Some works are known and people might have reached out to us proactively about them.”

Most works were for years displayed in the couple’s apartment, which stretched almost the entire length of the seventh floor at Plaza Hotel.

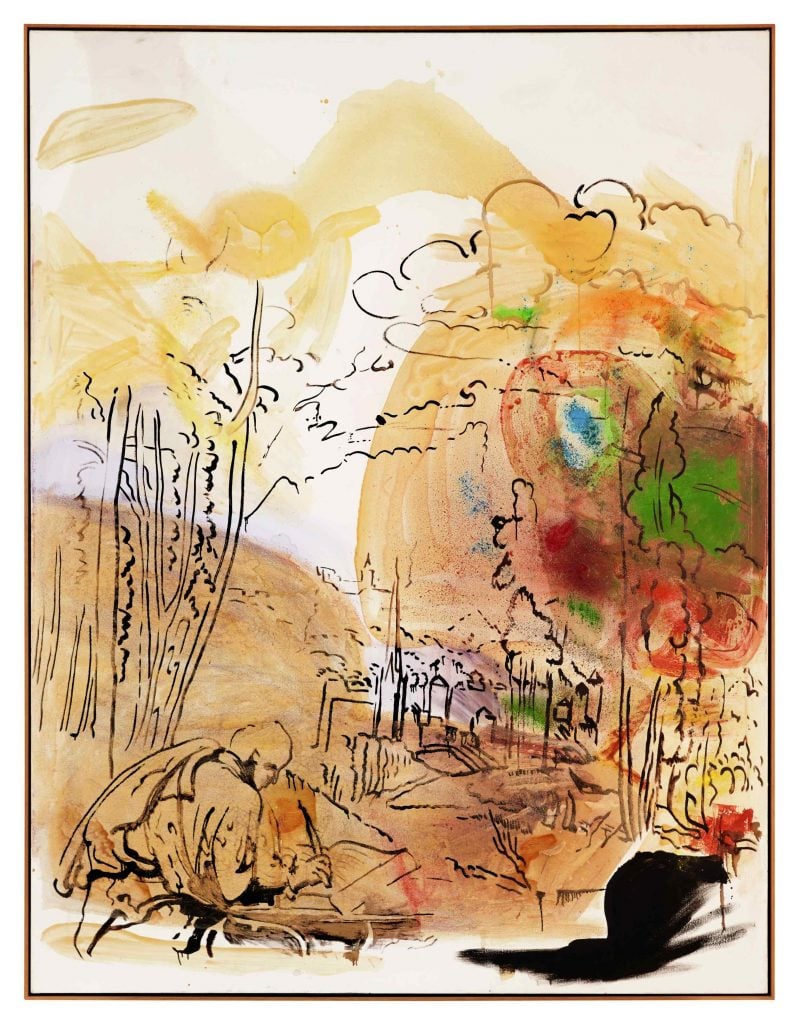

“The dialogue between the works themselves is rich, whether it’s two different statements on abstraction with the Rothko from 1960 and the De Kooning from 1961,” Lampley said. “Then not that long afterwards, you have a Polke from 1964, perfectly showcasing that really quick shift in the art world from abstraction to Pop.”

Sigmar Polke, The Copyist (1982). Photo: Sotheby’s.

The top lot of the group is Mark Rothko’s Untitled (1960), estimated at $35 million to $50 million. Like Rothko’s No. 7 (1951) that fetched $82.5 million in November, it was acquired by the Macklowes from Arne Glimcher, the founder of Pace gallery and the couple’s friend for 40 years. Pace also sold them Picasso’s bronze Jeune Homme, estimated at $1 million to $1.5 million; Untitled #11 by Agnes Martin, estimated at $4 million to $6 million; and Robert Ryman’s canvas, Swift, estimated at $8 million to $12 million.

Richter’s monumental seascape, almost 10 feet wide and 6.5 feet tall, is estimated at $25 million to $35 million. The 1975 photo-based canvas depicts billowy clouds and misty waters melt into each other, a dreamy marriage of elements. The work came up at Christie’s in London in 1992, failing to sell at $309,000. The Macklowes bought it six years later from Anthony Meier Fine Arts in San Francisco.

Now, the painting has the potential to become the most expensive figurative work by the artist ever sold at auction, surpassing Cathedral Square, Milan (1968), which fetched $37 million in 2013.

Gerhard Richter Seascape (1975). Photo: Sotheby’s.

Another highlight is Grand Nu Charbonneux (1944) the first large-scale nude by Jean Dubuffet. Estimated at $4 million to $6 million, the Art Brut-style painting was the only Dubuffet in the Macklowe collection.

Warhol’s Self-Portrait (1986) was part of his final “Fright Wig” series, painted months before his death in February 1987. Estimated at $15 million to $20 million, the 80-by-80-inch work was acquired from London’s Anthony D’Offay gallery in 1995. It has never been displayed in public since then. The most expensive 80-inch self-portrait from the series fetched $24.4 million at Sotheby’s in 2016.