Only the bold believe themselves free from the old gambling adage ‘the house always wins’ and Marcel Duchamp was one such individual: never short of self-confidence and always eager to subvert the system.

While idling among the gaming halls of the French Riviera in 1924, Duchamp was unmoved by the spirit of zealous gambling that surrounded him and struck instead by a conviction that he could beat the casinos with logic. The idea was in keeping with Duchamp’s drift in the 1910s away from the art world and towards chess, a sport he covered in weekly newspaper columns and played competitively.

Soon, Duchamp had concocted a scheme to crack roulette, one of seemingly endless dice rolls that produced exceedingly attritional gains. He was winning, only extremely slowly. What he needed was hefty financial backing.

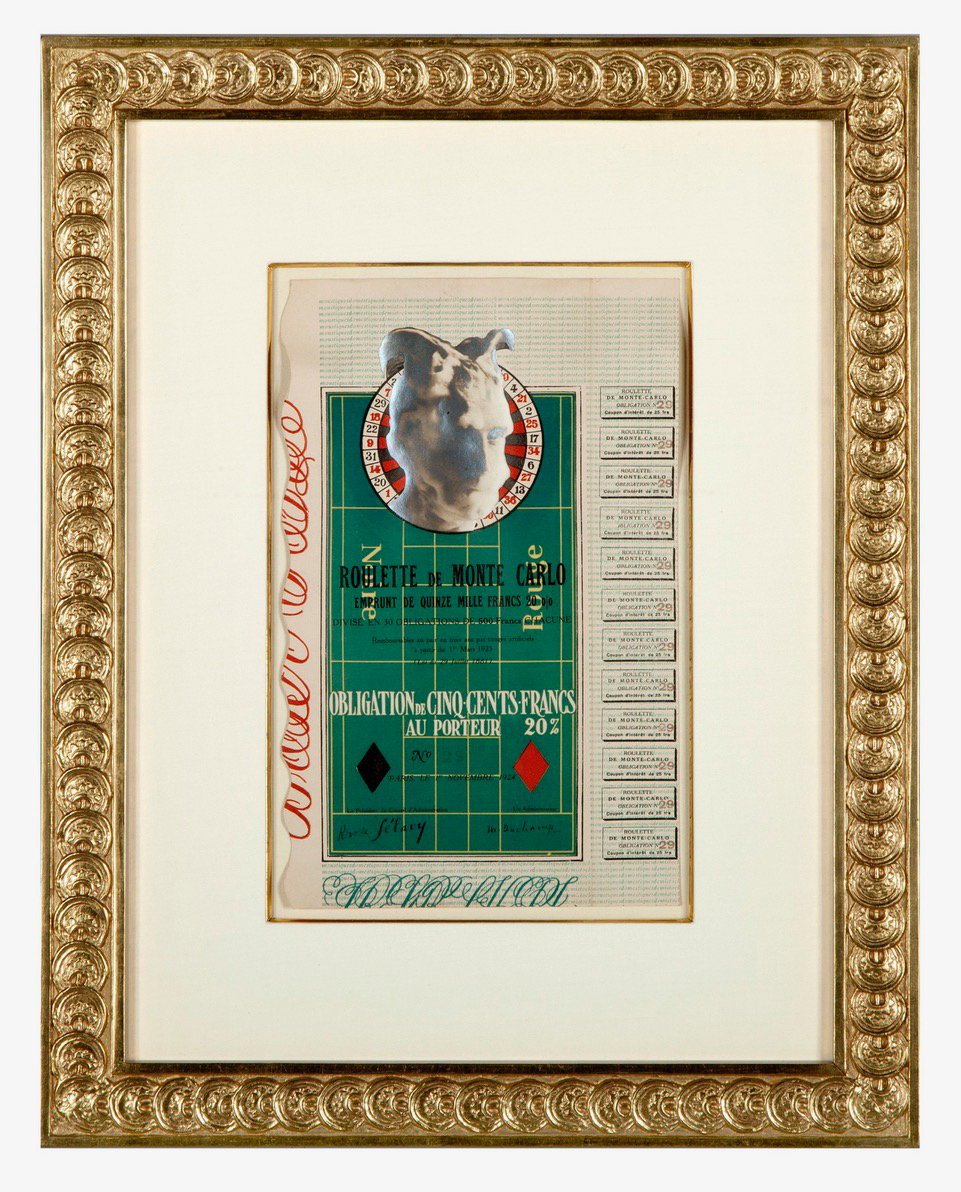

So began Duchamp’s Monte Carlo Bond, a work that is at once a continuation of his readymade practice, an irreverent critique of finance and gambling, and a bona fide legal document. Publicly at least, Duchamp may have quit painting, but he’d certainly retained an eye for art.

Duchamp planned to issue 30 bonds for his venture at 500 francs each (roughly $10,000 today) with shares repayable over three years at 20 percent interest, well above French bond rates at the time. It was, in essence, a crowdfunding endeavor aimed at art-minded members of the bourgeoisie and number 29 is now up for sale at the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair, courtesy of London’s Sims Reed Gallery.

“The whole is a beautiful conception. The format of the bond itself, the color elements,” Rupert Halliwell, Senior Bibliographer and Cataloguer at Sims Reed, told Artnet News. “As with so much of Duchamp’s work, it is prophetic and totemic, not to mention anticipating and subverting any interpretation.”

Sturtevant, Duchamp after Man Ray Portrait (1967). Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

The bond’s design is dominated by a portrait of Duchamp, taken by friend and fellow provocateur Man Ray, which looms over the green felt of a roulette table. His face is plastered in shaving foam with his hair raised and parted dramatically, is he posing as the devil or Mercury the god of money? You decide.

Further interpretation is demanded by the bond’s recurring background text, which reads “moustiques domestiques demi-stock,” a seemingly nonsensical pun that means “domestic mosquitoes half-stock.” In place of the standard articles of association listing the signee and location, Duchamp inserted “The French Law of July 29 1881,” which was the foundation of France’s freedom of speech laws.

Despite this playfulness, Duchamp intended for the bond to be legitimate. His father was a notary and he knew well how to validate a document; the bond is signed by himself and Chairperson of the Board of Directors Rrose Sélavy, his female alter ego. Additional validation came in the form of a 50-cent stamp, which he affixed to the bonds he issued—eight, possibly fewer.

The Sims Reed Gallery’s version is missing this stamp. Does this dampen the legitimacy of the bond? Halliwell doesn’t think so. “Does the stamp authenticate an inauthentic pastiche that is also a work of art? There is a danger of some Duchampian circularity of thought here.”

Such circularity applies to Monte Carlo Bond on the whole, a work that despite failing to defeat the house, succeeded over the long term in holding its value. Sims Reed Gallery will be asking $575,000 for it at the book fair.