The Art Detective

On Edge Before Miami Basel, the Art World Is Bracing for ‘the Question’

Could a heightened scrutiny of artists' personal beliefs impact the contemporary art market?

Could a heightened scrutiny of artists' personal beliefs impact the contemporary art market?

Katya Kazakina

When the art world descends on Art Basel Miami Beach next week, an unexpected question may preempt the usual chatter at the fair about the artists’ practice and prices, museum acquisitions and future exhibitions.

“For the first time you are starting to hear: What’s your position on the Israel-Palestine situation?” said Ralph DeLuca, a collector and advisor. “People want to know where the artists stand on this issue.”

The war in the Middle East has become a lightning rod in the art world since the barbaric attack on Israeli civilians by Hamas and the human toll after Israel’s fierce retaliation in Gaza. It exposed ethnic and generational rifts and unleashed existential anxieties.

When prominent artists such as Nan Goldin and Barbara Kruger signed a letter in Artforum in support of Palestinians without mentioning Jewish suffering, Jewish art dealers protested, and Jewish collectors removed the artists’ works from their walls. When Artforum’s editor-in-chief was fired, several staffers resigned in dissent. When social media accounts of artists lit up with proclamations of “genocide in Gaza,” they were met with accusations of anti-Semitism.

“In my 15-plus years of collecting art I’ve never seen the art world so divided,” said DeLuca, who is not Jewish. “It’s disheartening. We usually band together as a family in support of an issue like this. There were no people arguing about support of Ukraine and BLM, rallying against the ultra-right, marching for women’s rights. Usually there was a common thread most people agreed on—until October 7.”

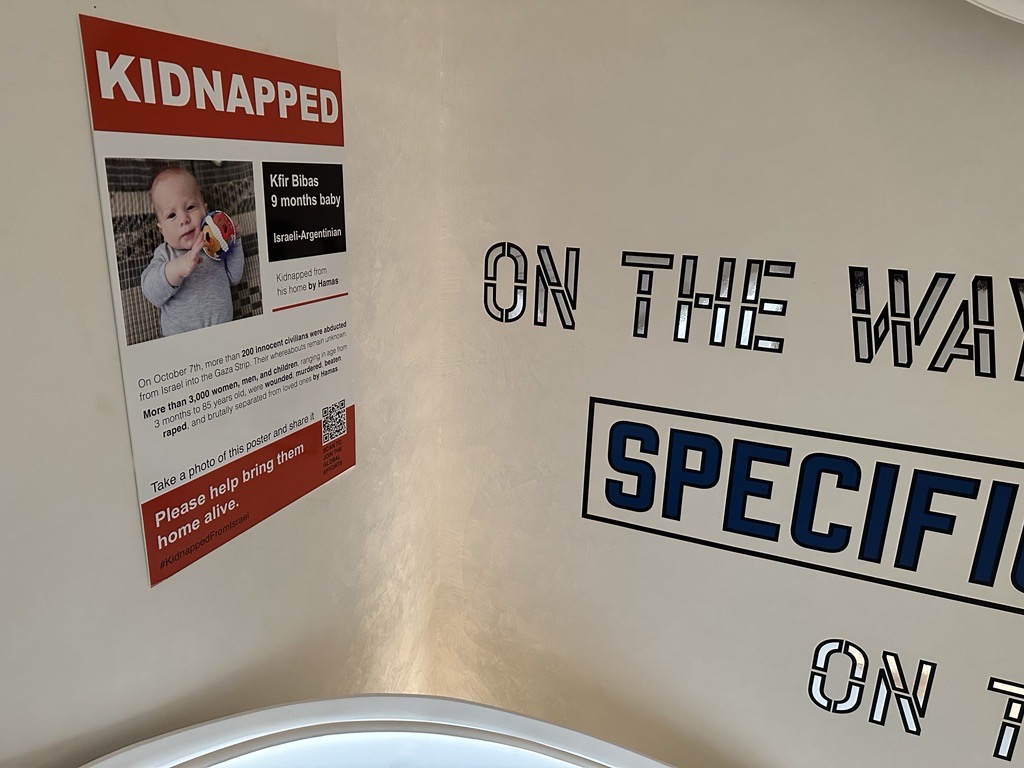

A “Kidnapped” poster next to an installation by Lawrence Weiner. Courtesy: Candace Worth.

How did we get here? How did the art world end up in a place where buyers are making decisions about aesthetic matters based on political points of view? There was a time when collectors bought art without ever meeting an artist, let alone inquiring about his or her beliefs.

The change has been a long time coming—a combination of the rise of identity politics, art as a lifestyle, rapid-fire acquisitions, and, of course, social media where artists, curators and collectors telegraph their beliefs for all to see.

The market for living artists has increased dramatically in part because it’s a community, one that the rich from around the world want to buy into. Collectors hang out with artists at art fairs, after-parties, and benefit galas. There’s a feeling of connection and belonging to an art world. The artworks on the walls have come to signal not just wealth and access, but also values. In recent years, the focus has been on inclusion and diversity, with particular emphasis on Black and female artists.

“Historically, Jews have bought very difficult work, dealing with race, gender, and religion,” DeLuca said. “There’s no contemporary art market without the Jewish support.”

But what happens when the artists and their patrons suddenly find themselves on opposite sides of the barricade? What happens when you can’t break bread with those you used to consider your tribe?

Some Jewish patrons feel so betrayed, they are walking away from the artists they’ve long supported. Others are skipping Miami this year.

“How do we approach Art Basel? Who do we buy from? Do we ask ‘the question’?” a Jewish art advisor and collector said this week, asking not to use her name.

She was one of more than a dozen art market participants I interviewed, including dealers, consultants, and collectors, who all acknowledged the rift over the war as a new factor for the trade.

“It’s making me question my work,” the art advisor said. “I thought this was my world.”

A demonstrator holding a Palestinian flag during a recent Strike MoMA protest. Courtesy of Strike MoMA via Twitter.

George Lindemann, president of the Bass museum’s board of trustees, said he’s going to start each conversation at the fair next week with a simple question: Is the artist a hater?

“Does the artist espouse hate or violence against anyone or any group?” Lindemann said. “If so, I don’t want anything to do with it.”

“The bottom line is,” said art advisor Candace Worth, “Jewish collectors do not want to look at art on their walls by artists who signed the offensive Artforum letter or who are using their social media platforms to voice anti-Israel and anti-Semitic viewpoints.”

The reason why anti-Israel views are offensive to many Jews (including those who disagree with its government) is because they see them as a proxy for anti-Semitism. Critics often don’t make a distinction between the State of Israel and the Jewish people, who frequently become targets of violence whenever emotions run high.

Private art dealer Mireille Mosler, the child of Holocaust survivors, moved to New York from Amsterdam in 1992, in part to not have to be always identified as a Jew.

But recently, an art world colleague made a comment about her “Jewfro” hair and introduced her husband as “a Jew from Frankfurt,” Mosler said. “There’s now a free-for-all where people single us out: That’s a Jew,” she said. “We are ‘the other’ again suddenly.”

The change has felt so profoundly disturbing, it’s propelling people into action. In early November, one of Worth’s clients put in storage several works by the artists who had signed the Artforum letter and replaced the empty spaces with large “Kidnapped” posters of the hostages taken by Hamas.

Another advisor is using the prism of the war to finalize the list of emerging artists showcased in a major corporate installation.

Advisors and collectors are eyeing works by artists who signed the Artforum letter for resale through galleries and auction houses.

“I don’t care if I leave money on the table,” said a New York-based collector of emerging art. “A lot of collectors are reevaluating their collections in the light of what’s happening. We’ll see a lot of work sold. Artists are very defensive about it. They go and trash Jews, in general, and Jewish collectors, in particular. It’s not fair. It’s my money.”

The collector draws the line at the artists’ “support for Hamas,” she said. She is planning to go over her inventory methodically early next year and select the works for sale.

Both positions should be respected, according to DeLuca. “Artists should have freedom to post and say whatever they want,” he said. “We are in America.” By the same token, he added, collectors should be free to not buy (and to sell) art if they disagree with the artist’s views.

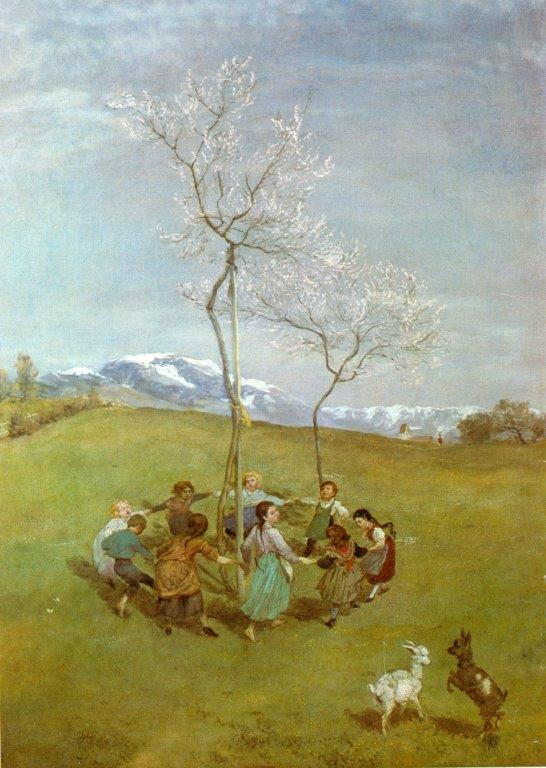

Frühling im Gebirge/Kinderreigen by Hans Thoma, one of the official painters of the Third Reich. Courtesy: Dr. Oetker.

Not everyone is eager to edit their collections.

“I am not boycotting artists,” Mosler said. “I am not looking for friends when I buy art. I am interested in their art, not their political views.”

Mosler’s stance extends beyond today’s political divisions. Just this week, a client asked her to bid on a painting by early 20th century German artist Hans Thoma (1839-1924), one of the official painters of the Third Reich, whose artworks were acquired for Hitler’s personal collection.

“I am not telling my client he can’t buy that,” said Mosler. “It’s not my role to talk collectors out of the art they enjoy.”

Thoma was the subject of a 2013 retrospective at the Städel Museum in Germany, which was organized by Max Hollein. One of the themes it addressed was: “If the artist was on the wrong side of history, can we still appreciate the art?” Mosler said.

A similar question looms for many today. The impact of these sensitivities on the art market remains to be seen, but the timing isn’t great. The art market contracted this year. Will the selectivity by Jewish collectors further reduce the velocity of transactions at the biggest contemporary art fair in the U.S.? What about individual artist markets? Will the art community be able to come back together? Next week may provide some answers.