Art & Exhibitions

Italian Pop Art Legend Mimmo Rotella Delights at London’s Robilant+Voena

It's the first retrospective in the UK of the Italian artist who died in 2006.

Photo: Courtesy Robilant+Voena

It's the first retrospective in the UK of the Italian artist who died in 2006.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

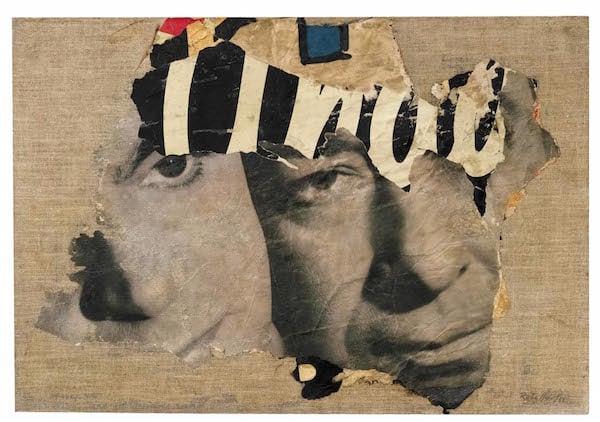

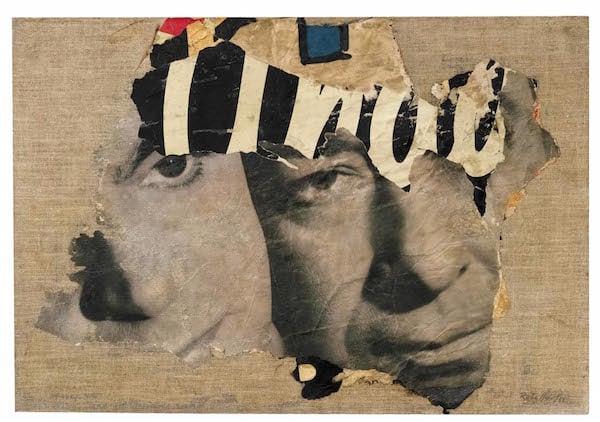

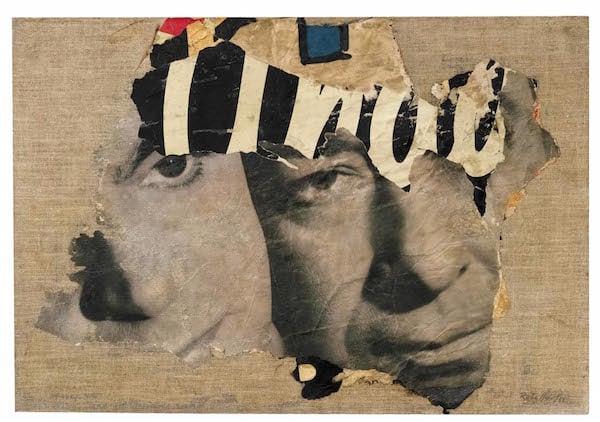

Mimmo Rotella, Collage 12 (1954)

Photo: Courtesy Robilant+Voena

It’s easy to dub the artist Mimmo Rotella (1918-2006) as the Italian answer to Andy Warhol. And, indeed, Rotella was a Pop artist. His obsession with advertising and film, and the manner in which he turned elements from mass media into iconic works of art, makes the comparison with his American contemporary a logical one.

But, as this retrospective exhibition at the London gallery Robilant+Voena attests to, Rotella was much more than that, creating a polymorphic oeuvre where techniques and styles were fluid, and constantly evolving.

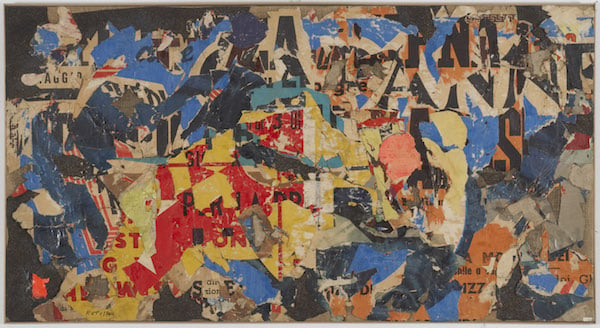

Upon entering the gallery’s Mayfair space, the first works that steal one’s attention are a group of décollages that Rotella made in the second half of the 1950s by appropriating and intervening street posters.

Sixty years after their completion, these works read as a transatlantic crossover between the European school of Dada collage—of which Kurt Schwitters was the master—and the then-emerging American trend that mixed collage with pictorial elements. Pioneered by Robert Rauschenberg, this style would come to epitomize the transition from Abstract Expressionism to Pop.

The décollages, Collage 12 (1954), Legr (1958), and [Senza titolo] (c. 1960), display legible traces (shapes, letters) of what the posters used to depict, but Rotella’s painstaking labor of peeling creates mazes of colorful abstractions that are as beguiling as they are complex.

In the following room, which contains works made in the first half of the 1960s, Rotella has evolved into a more representational and Pop-infused style. His décollages Birra! (1962), Arachidina, and Il cantante (both 1963) also employ advertising posters as raw material, but the original imagery is more ostensible, and the technique of tearing away has only been applied to specific parts of the composition.

The result is a Mediterranean version of then-dominant Anglo-Saxon Pop Art style. Less Andy Warhol and Richard Hamilton and more Federico Fellini, it’s a veritable tribute to the Italian vernacular.

Mimmo Rotella, I due visi (1962)

Photo: Courtesy Robilant+Voena

Subsequent works from the mid to late 60s, however, evidence a change of method. The newly available mass printing techniques proved to be a fertile ground for Rotella’s formal experimentations.

To create works like Uno sguardo dal bicchiere, Cavalcata Selvaggia (both 1966), and Grande source (1966-71), all showing Artypo on canvas—a printing method using graphic typography techniques—Rotella approached billboard printers. He convinced them to give him the large sheets of paper that were employed to warm up the printing machines, which were used and re-used over and over again.

Their repeated use created multilayered images where elements from disparate ads were randomly juxtaposed, and which Rotella then selected, cropped, and framed. These works, which indicate the artist’s sharp eye for composition, predate the work of subsequent appropriationists such as Richard Prince.

In the late 80s, Rotella’s work turned towards social affairs, employing photographic reproductions of iconic covers of magazines such as Time and L’Espresso to comment on the fraught relationship between the media and politics.

But, for all the Pop and riotous energy that this exhibition suffused, what struck me most about Rotella’s prolific and uncompromising oeuvre were his most muted works.

In the late 1950s, before his first colorful décollages, Rotella created a series of works including Levigo con macchie, Materia 5 (both 1956), and A forma isolate (1960), that also used street posters as a point of departure. But what he did then was to display the back of posters, torn from the urban walls of Rome.

The exquisite play of textures that resulted, complete with pieces of lime mortar and all, can be read as flat sculptures in beige and brown colors; a celebration of materiality and nuance that wouldn’t look amiss as part of an exhibition of young contemporary artists.

Upstairs, Rotella veers even more into sculptural territory. His work Blank Metal (1992) is deceptively simple: a sheet of zinc metal applied to a wooden board, and partially covered with white paper. But the result is oddly engrossing, and one could easily get lost in the ochre oxidation stains of the metal, or in the small air pockets and folds created by the glued paper.

The breadth of this exhibition reveals an artist as able to think big and brash as he is to craft delicate understated pieces. A tireless experimenter who is always a joy to rediscover.