Galleries

Minimalist Master of Light Dan Flavin

He tried the priesthood and the army before he decided on fine art.

Photo: courtesy Vince Fine Arts

He tried the priesthood and the army before he decided on fine art.

Amah-Rose Abrams

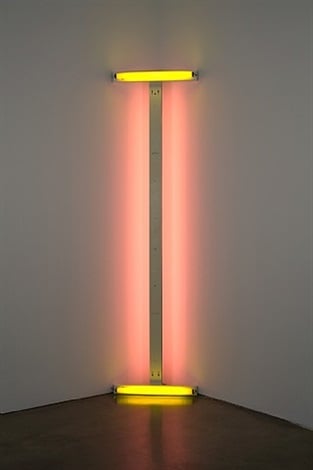

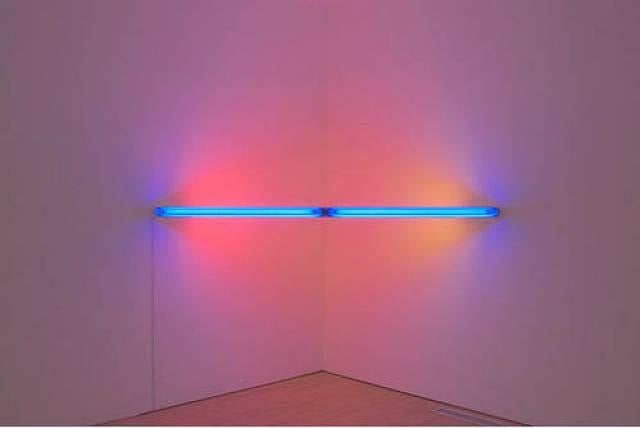

Dan Flavin untitled (to Barry, Mike, Chuck and Leonard), (1972–1975)

Photo: courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery

Dan Flavin’s work consists of few materials—color, light, and space. What he managed to do with these seemingly simple elements has amounted to an important and lasting legacy that changed the course of 20th century art.

A native New Yorker, he initially intended to become a priest until he left his religious studies and joined the US Air force. While serving in Korea between 1954 and 1955, Flavin began to study art as part of an extended course run by the University of Maryland.

On returning to New York in 1956, Flavin enrolled at the Hans Hoffman School of Fine Arts under German Expressionist painter Albert Urban, before studying art history at the New School for Social Research and drawing and painting at Columbia University.

Flavin’s first works were paintings inspired by the Abstract Expressionist movement. There was a spirit of fun and experimentation at the start of the 60s, and artists were keen to push the boundaries of painting as far as they could go. By 1959, Flavin was making works out of found objects, mostly used drink cans.

Dan Flavin Untitled, (1969)

Photo: courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery

In 1961, the young artist was working as a mail room clerk in the Guggenheim Museum, where he met and befriended fellow artist Sol LeWitt, critic and curator Lucy Lippard, and minimalist painter Robert Ryman. It was also in this year that he began experimenting with fluorescent lighting.

Flavin’s Icons series, created in 1961, consisted of shallow boxes with fluorescent bulbs that were attached to their sides or along their edge.

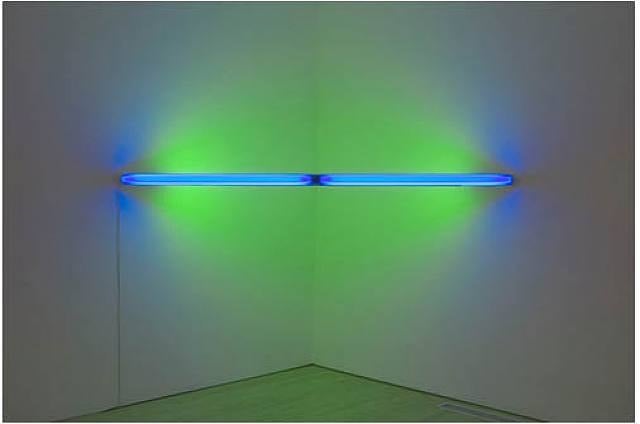

These light works came out of a Minimalist ideology. Flavin used factory-made colored, fluorescent light fittings, and gradually developed his work into full-scale, site-specific installations—creating a completely new artistic language in the process. All the while Frank Stella literally pushed the boundaries of painting through shaped canvases, Flavin was taking color out of the confines of the canvas and into our corporeal space.

“Though the installation must look very stable, it’s easily understood with a slight confounding paradox, as the lamps operate out of the corners and with the corners,” said Flavin when talking about his work in the documentary American Art in the 1960s.

As the same work could be installed differently according to its location, the inherently site-specific nature of Flavin’s works became apparent as a key element to this new approach to art-making.

Dan Flavin, Untitled (1969)

Photo: courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery

Diagonal of Personal Ecstasy (the Diagonal of May 25, 1963) is considered to be Flavin’s earliest “mature” work. Dedicated to Constantin Brâncuși, the piece consisted of a single diagonal yellow fluorescent bulb.

Flavin used a deliberately limited color palette—red, blue, green, pink, yellow, ultraviolet, and four different whites. The colors weren’t custom-made, but rather factory defaults. Each color in an individual installation is interchangeable, meaning that works can be installed in various ways depending on the space, over time.

“I think that I’m one of those people who, for better or for worse, really believes in some of the simplest materials being the best to think through,” he told Tiffany Bell in 1982. “It’s probably an old view and it may go […]. One sees the ups and downs of contemporary painting, where old anxieties come through the brush again. You say to yourself, well, who gives a damn.”

Dan Flavin Untitled (1969)

Photo: courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery

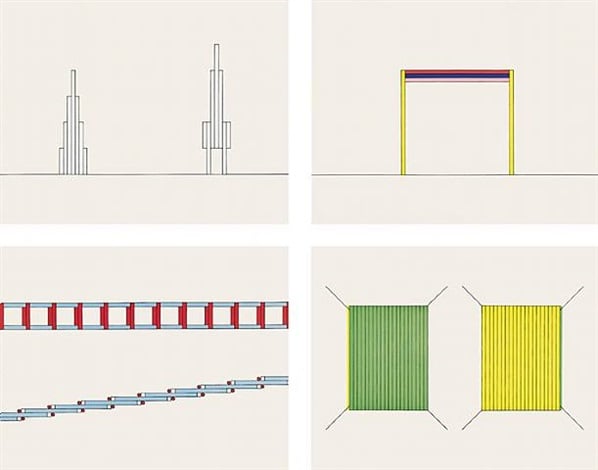

Experimenting with light, color, and space throughout the 1960s, Flavin began to reject working in the studio altogether, preferring to install in the actual gallery space where the work would be seen—a logical and practical move. He would initially produce drawings, using them for reference to make finished work once they had been purchased, and would supply the buyer with a certificate which could be used to redeem any future repairs.

Flavin’s career began to explode. He completed his first installation, Greens Crossing Greens (to Piet Mondrian who lacked green) in the Netherlands in 1966, then in 1968 he outlined an entire space in ultra violet light for Documenta 4 in Kassel. Just three years later in 1971, he bathed the circular, open interior of the Guggenheim Museum in light.

Dan Flavin Projects (1963-1996, 1996)

Photo: courtesy Schellmann Art + Furniture

Throughout the 1970s, Flavin completed many installations for the Dia Art Foundation—a relationship which not only spawned the Dan Flavin Institute in Bridgehampton, NY, but also the “Dan Flavin: A Retrospective” exhibit which toured the world and was shown in spaces such as the Hayward Gallery in London, the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville in Paris, and LACMA in Los Angeles.

Falvin’s lasting influence can be seen in the work of contemporaries such as Robert Irwin and James Turrell, who went on to outlive him. Flavin died of complications due to diabetes in 1996, at the age of 63.

Today, visitors to Dia:Beacon in upstate New York can contemplate a permanent installation of Flavin’s work, installed along the building’s long hallway. Through his work, his legacy shines on.