Art & Exhibitions

Moby Talks About His Masked Innocents, Hiding from Shame

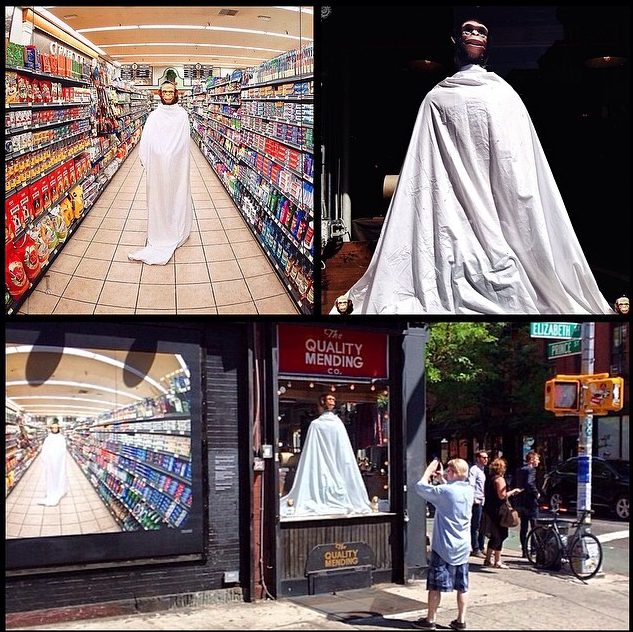

The artist's new solo show, "Innocents," puts post-apocalyptic guilt on display.

The artist's new solo show, "Innocents," puts post-apocalyptic guilt on display.

Alessandro Berni

Singer-songwriter and photographer Moby believes that the apocalypse has already happened: This is the premise of his series of photographs “Innocents.” The visual companion to the artist’s Innocents album released in October 2013, “Innocents” is currently on view at the Emmanuel Fremin Gallery in Chelsea.

Fans of the artists already know that some of these images have already made appearances elsewhere—first, in May, at the Art for Tibet auction, and over the summer, outside Quality Mending at the corner of Elizabeth and Prince Streets in Manhattan.

Photo: @robertstevens on Instagram.

Who are these innocents? Unlike pre-apocalyptic cult members attempting to protect themselves against coming trouble, these folks are walking the earth in a state of post-apocalyptic shame and guilt. They are collectively burdened by the self-knowledge that they themselves helped to bring about the destruction of the world as they once knew it. As the gallery explains, Moby’s many masked innocents are “are doing everything in their power to conceal themselves.”

Seeking a way to vibe to a post-apocalyptic consciousness, artnet News caught up with Moby at Emmanuel Fremin to discuss his solo show.

Was “Moby” born with your passion for photography or for music?

Both came into my life very early. I started playing the guitar at the age of 10, and at that age my uncle Joseph Kuglelsky, who at the time was a photographer for the New York Times, gave me my first camera, a Nikon F.

So, how did you come to be a professional in both the arts?

Compared to learning photographic techniques on a manual camera, the guitar was easier to make quicker progress with. As a result, the musical success came much earlier. In college I took two degrees, one in philosophy and one in photography.

About photographic techniques: How did you manage the change from film to digital?

I remember that I began to talk of digital cameras with my uncle in 1989. Conscientiously, I started using them beginning in 1993.

How has the way you take pictures changed thanks to this technology?

Not a lot. As a boy I didn’t have a lot of money, and for me film and printing was expensive, so we put in a lot of thought before actually taking a picture. Today, however, with digital you can take millions of shots of a single pose. I prefer the preparation of each shot, which takes more time, like when I was a boy with empty pockets.

What do you miss most as a result of the transition between film and digital?

Well, like everyone, I miss the atmosphere of the dark room.

The photos of this show seem to come from distant planets. Were they taken during your travels around the world?

Quite the contrary. They were taken in my backyard in Los Angeles, except for one, which I took in my local supermarket.

How did you end up collaborating with the Emmanuel Fremin Gallery?

Through a mutual friend, Lee Milazzo. Lee has a gallery in Connecticut and knew both me and Emmanuel.

Your show is presented as a rendering of life in a post-apocalypse world, represented by anonymous empty spaces filled with masked faces—why?

Because that’s what I see around me. Urban alienation is alienating.

Why are all the innocents wearing plastic masks?

They are ashamed because of their role in a society and in a culture incredibly and unnecessarily destructive.

Your show evokes a fierce desolation, a total absence of consolation. From your photos, it appears that not only is there is nothing to hope for, neither is there anything to despair about. But is this really the world as you see it?

What I see is that every individual is innocent; it is the community that is guilty.

Talk about a post-apocalyptic consciousness in preparation for the real apocalypse. None of us is dead, none of us is alive. Are we only masks?

We are something. There is a widespread awareness of what I have chosen to represent, but the common people, the innocent people, instead of looking for some secret formula to save themselves from this apocalypse that’s coming, they continue to live their lives, the apocalypse, as it were—to recite a script predetermined by someone else.

Let’s switch gears. You were born in Harlem and spent your childhood in Connecticut. Then you lived in New York until a few years ago, when you decided to move to Los Angeles. What were the reasons for this?

Well, I got sober. New York City is an amazing place to be a drunk. Los Angeles is much better for living a healthy lifestyle. I also wanted to be warm in the winter.

I believe you, even if there is something else behind your decision to move out of New York.

I hate to say it, but I’ve lived in a New York that simply no longer exists. Everything is gone, say, in the last 15 years. The artists that live in this city, they live worried. The costs are too high. Manhattan has been emptied of its soul and its artists in less than a generation. Today it is more of a place where people buy art, rather than a place where people make art. In Los Angeles, on the other hand, there is a community of artists which I joined willingly, and we and they can afford to live there cheaply.

Can you say something about your next tour?

On my next tour I am supporting an ambient album I recorded a year ago, an accompanying album to Hotel, called Hotel Ambient. I will only do two dates, both in California.

By the way, few people know that your first band was Vatican Commandos, a hardcore punk band. Are you still inspired by hardcore punk music?

Yes, I am currently playing with Travis Barker [the drummer of Blink-182] and Toby Morse [the H2O singer].

Do you all have a name?

Sure. We are called Friends of Animals, a group of militant vegans.

Is there a CD coming with them?

Maybe.

Moby’s series of photographs “Innocents” is on view at the Emmanuel Fremin Gallery, 547 West 27th Street, through December 31.