Art Fairs

Market for Virtual Reality Art Gets Tested at Moving Image Fair

The new medium opens new frontiers for art, as well as a few new obstacles.

The new medium opens new frontiers for art, as well as a few new obstacles.

Brian Boucher

“I can count on two hands the collectors who are buying immersive media works,” said Moving Image fair co-founder Edward Winkleman at a preview on Monday, kicking off Armory Arts Week in New York. “But I’m encouraged for the future by the number of lawyers and doctors who are buying virtual reality headsets for their kids, and might want to use them for something more than gaming!”

Winkleman started the Moving Image fair seven editions ago with his partner, Murat Orozobekov, to give video works a commercial platform and a place where they could have the concentrated viewing an art fair offers. Launched in New York, the fair has since gone global, adding an Instanbul edition. Over the last two years, the founders have turned their focus strongly to virtual reality and augmented reality, which make a strong showing at this small fair, with about a third of the 28 offerings engaging these technologies.

Winkleman and new-media curator Barbara London (a longtime Museum of Modern Art staffer, whose swan song there was a 2013 sound-art exhibition) chatted before the preview about the demands of presenting, selling, and conserving art in newer mediums. Even for video art, collectors and dealers are still hashing out templates for purchasing contracts that can cover issues like optimal presentation environments and terms for possible future conservation, which can include upgrades to newer technologies. “Otherwise,” said London, “the piece dies.”

Still from Naoko Tosa, Genesis Yellow (2016), courtesy Ikkan Art Gallery, Singapore.

Those kinds of questions go into overdrive with virtual or augmented reality, in which, Winkleman pointed out, there are many moving parts, including computer coding and headsets, which, in a single piece, may come from various companies. And hardware is changing rapidly in what he described as an arms race among makers of products like the Oculus Rift and the HTC Vive, both in evidence at Moving Image.

The headset-driven, immersive, VR works on offer engage a range of artistic interests. Upon entering the fair, the first you encounter is Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s Oculus Rift piece, Primal Tourism: Island (2017), a virtual visit to the island of Bora Bora, in which a tiny room of plywood and plastic becomes a French Polynesian paradise. Elsewhere, there’s Rebecca Allen’s narrative study of hallucination and of the interior of a human brain, presented by London’s Gazelli Art House.

World and Place Evaporating (2016), by Christopher Manzione and Seth Cluett, impressed even tech geeks present with an eerie but subtly integrated moment in which, with the use of a camera mounted on the front of the headset, the participant’s own hands become visible as she wanders in a virtual forest.

All that work comes at prices that, Winkleman pointed out, are comparable to those for video works. The VR and AR works come in editions of between three and eight, and prices range from $5,000 to $25,000. Steensen’s Bora Bora piece is tagged at $7,000, as is Manzione and Cluett’s installation; both are in an edition of five. The priciest work in this category, at $25,000, is Tamiko Thiel and Zara Houshmand’s Beyond Manzanar (2000), in which viewers use a joystick to explore World War II-era internment camps. It comes in an edition of three.

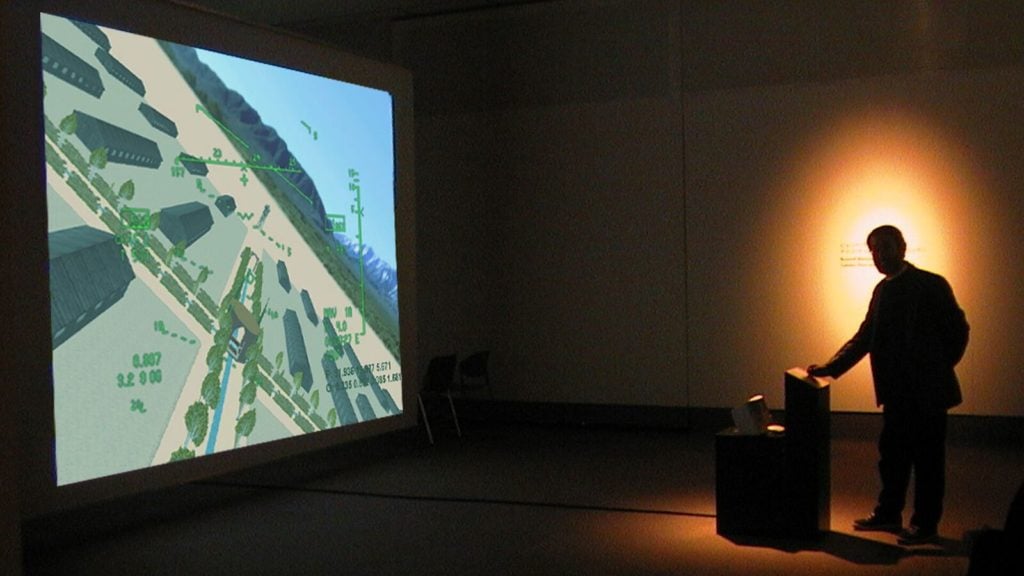

Installation view of Tamiko Thiel and Zara Houshmand, Beyond Manzanar (2000). Image courtesy Moving Image.

Behind the sometimes very impressive effects, some of the artists are engaging topics that stimulate artists in more traditional mediums. Steensen’s trip to Bora Bora, for example, partly imagines that setting (and he’s imagining it too, since he’s never been) in a post-ecotourism environment, after years of continuing climate change.

John Craig Freeman’s geolocated augmented reality piece (it’s based on some of the same tech that brought you Pokémon Go) overlays scenes from St. Petersburg, Russia with the topography of New York as you look at it on your phone or tablet. Freeman is exploring questions about the nature of the public sphere and public monuments in the digital era. (Its echo of suspicions that Russian intelligence helped nudge the president into the Oval Office is a nice bonus.)

For me, the most compelling piece was one without any such overt topical concerns. Brenna Murphy’s mesmerizing installation Lattice~Domain_Visualize (2017), on view with Portland, Oregon’s Upfor Gallery, places the participant in a swirling, kaleidoscopic, bright-hued tower that seems to extend nearly infinitely above and below, with a rushing soundtrack. It comes in an edition of three plus an artist’s proof, with a price tag of $8,500 including computer, HTC Vive, and floor prints.

In a 2014 interview with Art in America, Murphy expressed a hope for “some kind of utopic digital commons, where we can use our connectivity to transcend our current state and bring a more advanced outlook to our place in the world.” That belief in the possibilities of the new medium comes across in the exhilarating encounter with the piece itself, in which digital means add up to an experience that can get mystical.

Moving Image New York is open through March 2 at Waterfront New York Tunnel, 269 11th Avenue, between 27th and 28th Streets, Monday-Wednesday 11 a.m. to 8 p.m., Thursday 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.