Although Diego Velázquez is best known as the star of Spanish court painters, he occasionally turned his gaze toward humbler subjects—as in his 1650 portrait of his mixed race, enslaved assistant, Juan de Pareja, whom he depicted with directness and dignity. As one account has it, when the artist sent his assistant to show the painting to his friends, they looked back and forth between Pareja and the canvas, unsure which one to talk to. The painting was just as impressive in 1970, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased it for $5.5 million, then the most expensive work ever sold at auction.

The Met is not always known as a trailblazer, but this purchase was decades ahead of the curve. Today, under social pressure to reform, museums are racing to correct longstanding prejudices not only in their Modern and contemporary holdings, but also in their Old Masters collections.

In a market not particularly known for responding to current events, museums are initiating a shake-up as they buy and exhibit the work of artists of color as well as depictions of non-white subjects.

Experts in the field point out that a few U.S. institutions, including the Philbrook Museum of Art, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the Flint Institute of Arts, in Michigan, have been diligent in this area for years. The Flint, for example, whose home city is more than half African American, acquired a Jean-Baptiste-Jacques Augustin study of an unknown Black man in 2003.

But since the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, more museums have joined the effort, and the push has gained particular momentum since the 2020 murder of George Floyd. “It’s a broad movement,” said dealer Robert Simon, “and American museums are at the forefront.”

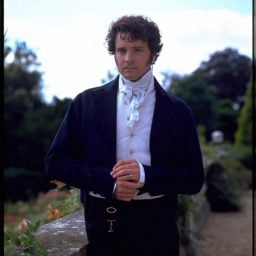

Juan de Pareja, Dog With a Candle and Lillies (ca. 1660s). Courtesy of the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.

Art sellers are scrambling to meet the demand. “It is extremely rare to find Old Master artists of color, but we are hearing a lot of interest from collectors and museums,” Calvine Harvey, vice president and Old Master specialist at Sotheby’s New York, told Artnet News. When Sotheby’s does land one, she said, they prefer to bring them to public auction rather than a private-treaty sale. Touring the painting to its global showrooms allows time to drum up interest and sometimes even establish attribution, if the paintings’ creators are unknown.

A recent sale of a work by Pareja himself indicates the ferocity of the competition. Only two of his paintings have come to auction, according to the Artnet Price Database. Portrait of the Architect José Rates sold at Sotheby’s Madrid in 1990 for about $124,000 against a high estimate of about $95,000. The 2019 sale of Dog With a Candle and Lillies (early 1660s), at Pandolfini Casa d’Aste in Florence, however, generated much more excitement. Bearing a high estimate of less than $9,000, it went on to fetch more than 30 times that, almost $271,000.

The painting was subsequently bought by the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields this year. It’s the first purchase from a $20 million fund to acquire work by BIPOC artists that the museum established after staff leveled accusations of a toxic, racist culture. It will go on view October 29, in the exhibition “Juan de Pareja: A Painter’s Story.”

Superstars and Unknowns Share the Spotlight

The thirst for canonically corrective material spans all levels of artistic fame. Sometimes these acquisitions are by artists who, although remarkably well known in their day, have been overshadowed by history. In 2018, the Clark Art Institute, in Williamstown, Massachusetts, announced with fanfare that it had acquired a significant history painting by Guillaume Guillon Lethière, Brutus Condemning His Sons to Death (1788).

A Guadalupe-born competitor of Jacques-Louis David, Lethière had shown the work at the Salons of 1795 and 1801. In the press release announcing the acquisition, Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates said, “I was delighted to hear that the Clark has acquired an important painting by Guillaume Guillon Lethière, who is widely recognized as the first major French artist of African descent. His celebration as an artist of great skill and significance is long past due.” The painting had been in private hands for more than 200 years.

Guillaume Guillon Lethière, Brutus Condemning His Sons to Death, 1788. Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

In other cases, even paintings of obscure origins command high prices. In January 2020, the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) purchased the mid-18th-century Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom at Sotheby’s New York. Showing an unknown woman, seemingly of African descent, in a silk gown with pearled jewelry and silver earrings, the canvas soared above its $20,000 high estimate to fetch $68,750. The only visible signature was “J. Schul”; the curators have since determined that the painting is by the little-known Jeremias Schultz, a portraitist who worked in Amsterdam.

“There are many curators who have been doing this work for a long time, and many museums with great collecting histories,” Adam Levine, the museum’s assistant curator of European art, told Artnet News. “But I do think I’m part of a new generation of curators of European art who are part of these social movements, and part of our mission is sharing stories that are richer, more inclusive and more honest about the history of Europe, which has never been monolithically white.”

To contextualize the work for a contemporary audience, Levine and his fellow assistant curator Monique Johnson recorded nearly two hours of interviews (available on the museum’s website) with a conservator, a botanist, clothing experts, and an art historian focused on Black diasporic art.

The AGO’s painting is an unusually desirable one, noted Calvine Harvey, due to the apparent status of the sitter. “Museums are especially looking out for paintings where people of color are shown as independent people, rather than enslaved, or the more racist images that are tougher to see from the contemporary eye.” However, she added, “I think museums might be interested in even those” because they reflect the reality of the times.

The Right Kind of Representation

The St. Louis Art Museum has just installed a newly acquired canvas by Flemish artist Justus Suttermans (also known as Sustermans), the triple portrait Domenica delle Cascine, la Cecca di Pratolino, and Pietro Moro (1634). It shows three Medici family servants, a rarity from an era when portraiture typically depicted the powerful.

As for Moro, who appears at right, “It is extraordinarily rare for the name of a Black figure to come down to us,” according to a description of the work by dealer Robert Simon, who sold the painting. What’s more, Moro sports earrings and a fine cloak.

Justus Suttermans, Domenica delle Cascine, la Cecca di Pratolino, and Pietro Moro (1634). Courtesy of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

It’s one of just two depictions of non-white subjects in the museum’s Old Master collection, the museum’s curator of European art to 1800, Judy Mann, tells Artnet News, the other being a 1660s marble Bust of a Man by Melchior Barthel, acquired as far back as 1990. The latter “has proven a reassuring moment in the galleries,” Mann said, “where people feel that we do have things that look like them.”

While she would love to add work by non-white artists to the collection, Old Masters of color are very few, Mann said, citing Juan de Pareja as one example. “His work does come on the market,” she noted, but is rare enough that she suspects her museum would be priced out.

“Dealers know that curators are now looking for this material,” she said, “and I imagine that museums will be seeking a growing list of artists of the African diaspora.”

When a market heats up, concern about authenticity also rises. “Absolutely, that’s something we’re discussing,” Philbrook Museum of Art director Scott Stulen told Artnet News. “Anytime something gets overheated, there’s going to be some fakes that come on the market. We’re absolutely doing our due diligence.”

By way of a strategic deaccession soon after he arrived five years ago, the museum established a $15 million fund to acquire works by artists of color. All the same, small and medium-size museums like his are often priced out, he said, even at modest levels. When preparing to bid on a piece estimated at $5,000, for example, the museum might be prepared to offer as much as $25,000—“but they end up going for $50,000.”

And because such works are so rare, there are hardly any historical prices to compare them to in order to convince board members and donors of the works’ value.

Contextualizing Colonialism

While museums and private buyers alike are now centering race in their collecting, customs can change much more quickly in the contemporary arena, where top-flight artists of color are making new work every day. Among Old Masters, said Simon, “it’s a challenge to find works of quality.”

This is leading some curators to start thinking more broadly about traditional classifications, reaching into works from colonized regions or by diaspora artists. “Museums are rethinking just everything,” Judy Mann said. “We are trying to make more interesting interactions. Europe has traditionally held pride of place, but that’s not going to be the case any more.”

José Campeche, Saint Dominic of Guzmán, around 1790s. © Art Gallery of Ontario.

The Art Gallery of Ontario’s Adam Levine is of the same mind. “Curators of European art that I speak to are really invested in charting a new path for this field,” he said. That framework also drove his acquisition of a painting last year by the 18th-century Puerto Rican artist José Campeche.

“I myself am Puerto Rican, and I’ve been thinking a long time about how to represent Puerto Rican art in the age of empire,” Levine said. “Campeche may not seem like a completely obvious choice for a European department, but in this way, we can engage our audience with important histories of colonization.”

Back in New York, the Met continues to engage with those same histories. Last year, it acquired Joanna de Silva (1792), a painting by English artist William Wood that depicts a Bengal woman who served as a nursemaid in the family of an officer with the British East India Company. The painting, which portrays its subject with no small amount of grandeur, has just gone on view amid a gallery devoted to 18th-century British portraiture.

What’s more, in spring 2023, the Met will present an exhibition focusing on Velázquez’s portrait of Juan de Pareja. As director Max Hollein told Artnet News via email, “This exhibition—the first devoted to enslaved labor in Spain, to the Met’s celebrated portrait, or to Pareja himself—will build from an historical context and celebrate Pareja’s own artistic achievement and legacy,” drawing a direct line to the Black creators of the Harlem Renaissance.