Art Fairs

A Haitian Artist’s Glittering Vodou Flags Steal the Show at Miami’s Faena Festival

How Myrlande Constant went from selling decorative embroideries at street markets in Haiti to exhibiting her beaded flags at museums around the US.

How Myrlande Constant went from selling decorative embroideries at street markets in Haiti to exhibiting her beaded flags at museums around the US.

Osman Can Yerebakan

“I woke up this morning and I thanked God, and I tell all the spirits ‘thank you’ for giving me the strength to make flags,” Myrlande Constant said, looking up at her colorful beaded Vodou flags suspended from the lobby ceiling of Miami’s Faena hotel. She was donning a jacket decorated with the same circular felt pieces she had used for one of the works at the unveiling of the second-annual Faena Festival, titled “The Last Supper,” an immersive exhibition that includes work by 23 artists, including Martha Rosler, Ana Mendieta, Camille Henrot, and Janine Antoni, in addition to Constant.

The 51-year-old Haitian artist’s eight large-scale flags, which are embellished in glittering beads depicting alternative versions of the Haitian religion’s myths surrounding food, unity, and solidarity, are her largest to date.

Faena Art curator Zoe Lukov first encountered Constant’s Vodou flags two years ago at the Miami gallery Central Fine and was struck by the artist’s interpretation of functional sacred objects with dense visual and narrative layers. Contacting the artist, who lives on top of a mountain overlooking Port-au-Prince, was a challenge, but Faena ultimately managed to commission Constant to make one flag, which later turned into two, and six other flags came from institutional loans. “While we spoke through a translator, I felt that we actually communicated organically—a really beautiful mutual trust developed almost immediately given a shared understanding for the goals of the project,” Lukov said.

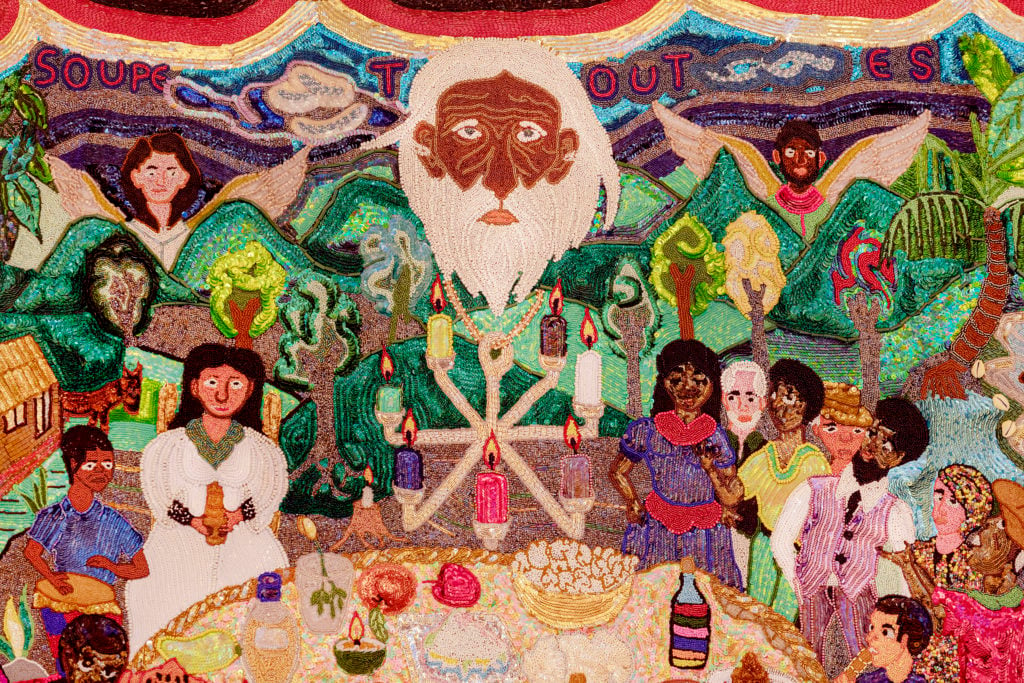

The 10-by-7-foot flag, Rasanbleman soupe tout eskòt yo, took four months to complete and required assistance from the artist’s five children. Constant, too, took needle in her hand at an early age, watching her seamstress mother embroider and sew beads onto wedding gowns. “I would skip school and make embroidery on dresses my mother left unfinished,” Constant told Artnet News about her early fascination with textiles.

Myrlande Constant, Rasanbleman soupe tout eskòt yo (2019). Courtesy of Faena Art, photo: Oriol Tarridas.

Her art stems from a deep belief in God—a Supreme Creator, and her narratives evolve around humans’ relationships to loas, who are representatives of God in physical world in Vodou, each with human-like characteristics and attributes. Evident in her flags on view at Faena is her balancing of the spiritual with a contemporary world view, in which figures in different colors, religions, and nationalities intersect and coexist over a scene of feast or death.

After the factory she worked for closed following the bloody anti-government demonstrations of 1986, which would eventually lead to the overthrew of Haitian president Jean-Claude Duvalier, Constant found herself making decorative embroideries of flowers to sell at street markets.

Watching a Vodou practitioner friend make paintings inspired Constant to push the limits of her own visual language. “Beads were the medium that I knew and I realized I could try and make paintings,” she said. Eventually she abandoned the flowers and started to embellish textiles with references to history, spirituality, and life cycle. It was around the mid-1990s when a woman who saw one of her flags told her to never let anyone call her work craft.

Installation view of Myrlande Constant works at the Faena Festival, 2019. From left: Marassa Trois, Rasanbleman soupe tout eskòt yo, Exorcism all 2019. Courtesy of Faena Art, photo: Oriol Tarridas.

Today, Constant works with a large wooden structure that anchors her meticulous process of applying beads onto fabric in various scales. She draws directly onto white fabric with a pencil before stretching it onto the structure from four angles. She repeatedly embroiders onto the drawing from the back of the flag, which she considers an instinctive process as much as a meditative one. Her blind view of the fabric during production is nowhere to be traced: Constant’s mesmerizing beaded flags boost bright colors and intricate figures engaging with mundane rituals such as dancing or eating, shrouding the artist’s religious references with the joy of everyday life and charm of sparkling colors.

She is a pioneer in a male-dominated practice, as well as a revolutionizer who brought buoyant colors and contemporary subjects onto flags and exhibited them at Pioneer Works’s 2018 exhibition Pòtoprens: The Urban Artists of Port-au-Prince and The Waterloo Center for the Arts in Iowa in 2017. She will have a solo exhibition at the Fowler Museum at UCLA in 2021. The current interest in her work isn’t surprising given the growing fascination in spirituality in art more broadly, particularly among women artists whose practices bridge introspection and immateriality with the physical world. Earlier this year, the Guggenheim’s massive survey of Swedish abstract painter Hilma Af Klint drew 600,000 visitors into the late artist’s contemplative and mysterious renditions of the metaphysical, becoming the museum’s most-visited exhibition in its history. Meanwhile, the 2017 Venice Biennale engaged with shamanism and primitivism in art that looked “inside” to reason the surrounding world and its cracking dynamics.

In a social landscape ridden by unpredictabilities and political complexities, it comes as no surprise that art which seeks comfort and answer in the sweeter side of the unknown gains visibility and access, and artists who have been religiously committed to a single practice but kept outside the mainstream, such as Constant, find space on gallery and museum walls.