Art & Exhibitions

Neo Rauch’s Paintings at David Zwirner Take a Page from the Brothers Grimm

It's the artist's largest solo show in New York to date.

It's the artist's largest solo show in New York to date.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

According to T.E. Lawrence, all men dream but not equally. The same could be said for painters—especially if one considers the latest batch of dreamscapes by Neo Rauch, currently on view at David Zwirner on 19th Street. Rauch’s latest painterly fantasias prove at once chimerical and anxiety provoking. The German virtuoso renders weird fairytale visions of sanatoria in monochrome and Technicolor; several of his pictures depict what look like East German versions of Hazelden, but run by the Brothers Grimm.

Rauch has long been a painter who deals in what he’s called “irreconcilable spheres” and “anachronistic hallucinations.” For more than two decades he has arrayed these elements freely, inventing characters and landscapes from his own head without recourse to either preliminary drawings or photographic sources. A committed fabulist, his signature artistic impulse has been to make realistic pictures that reject straight narrative subjects in favor of surreal scenes. “For me,” the artist has declared, “painting means the continuation of a dream with other means.” Here is this critic’s translation of the German’s poetic English: Rauch is not so much an interpreter as, effectively, an architect of dreams.

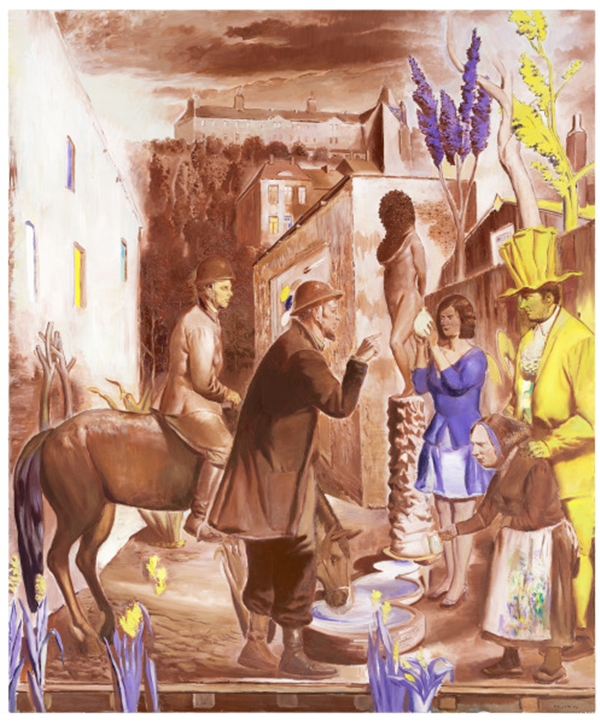

Among the current crop of 16 intensely oneiric paintings at Zwirner—the gallery says this is the artist’s largest New York exhibition to date—several major works present clues with which to unravel Rauch’s mysterious brand of anti-sense. Though famously reluctant to interpret his own works, there is no question the artist repeats various key subjects and motifs. Water and its life-giving properties, for instance, recur in many of Rauch’s recent canvases; so does the theme of illness and its opposite number—wellness. The show’s title, “At the Well,” gives language to a painting that depicts half a dozen figures and a single horse, drinking thirstily from a fountain. The fact that this, like other canvases, displays fresco-like effects, juxtaposes dry paint application with the artist’s repeated renderings of rivers, canals and coastlines—not to mention the bizarre sea creatures that appear amid rural and urban landscapes reminiscent of the artist’s landlocked Saxony.

Neo Rauch, Am Brunnen (2014).

Courtesy David Zwirner.

General malaise of the intensely Teutonic variety is a favorite concern of Rauch’s—he is on record as being deeply “identified with the history and tragedy of [his] country.” Yet this group of canvases appears to be touched by more personal experiences, suggesting time spent in the presence of health professionals and examination rooms. Rauch, in fact, has lately taken to speaking about his paintings with medical metaphors, using the terms “blood,” “nervous system,” and “skeleton” to describe their compositional scaffolding. Of course, Rauch’s latest inspiration is anybody’s guess: It could be family tragedy (he lost both his parents to a train accident when he was six months old), the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall, or serial meditations on modern-day plagues, like Ebola. Whatever the source, it has unleashed in the artist a series of works that repeatedly feature themes of sickness, recovery, and health.

One such painting titled Marina presents the sea rescue of an outstretched figure that is equal parts siren and crucified Christ. Her saviors, attired in hospital green, appear characteristically nonplussed by another vision-like presence: a floating totem made up of mismatched valves, a heart, and a spleen. A second picture, The Blue Fish, depicts a strangely citified version of the story of Jonah and the Whale. Painted in full color across two large panels, the canvas depicts not just buildings and a canal in irregular perspective, but a ginger-haired, red-clad nymph emerging from the belly of a steel-blue fish. The teal face of the male figure hauling her out suggests this modern day Virgin has drained some strange store of energy directly from him.

While Rauch previously limited himself to what he has called “a trinity of figures,” his current series has multiplied the number of characters in his canvases exponentially. The painting Healing Glade is a case and point. Another two-panel work, it features as many as a dozen figures (if one counts the modernist bust of Karl Marx on the right of the canvas) in a wooded clearing surrounding a man laid out on a stretcher. As is typical with Rauch, each figure appears lost in his or her own thoughts. In fact, his characters—along with the houses, forests, and a separate painting imbricated into the larger composition—look as if they have been collaged in from different worlds and separate pictures. Even when describing figures in purportedly curative relationships, Rauch tends to depict them as unsmiling, solitary, and alienated.

In the gallery walk-through prior to last week’s opening, Rauch delivered himself of a profound nugget of painterly philosophy. “It is not the task of painting to be an instrument of enlightenment,” he said. “The opposite is the case.”

An Eastern European skeptic who is also a romantic, the German artist delivers in this latest group of enigmatic paintings a world unsuited for renewal—but very much gallery-ready for enchantment, healing, and repair.