Innovators List

The Innovators: Alvaro Barrington on Gratitude, Bad Faith, and Why It Takes Eight Galleries to Raise an Artist

"My most expensive mistakes are when I don't rely on community," Barrington says.

"My most expensive mistakes are when I don't rely on community," Barrington says.

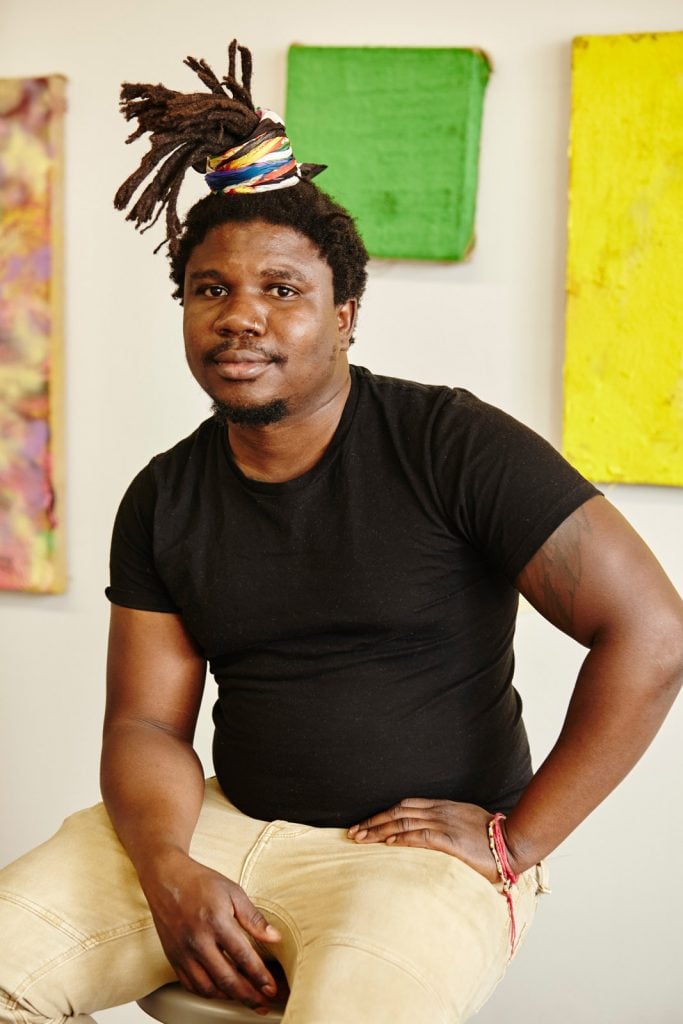

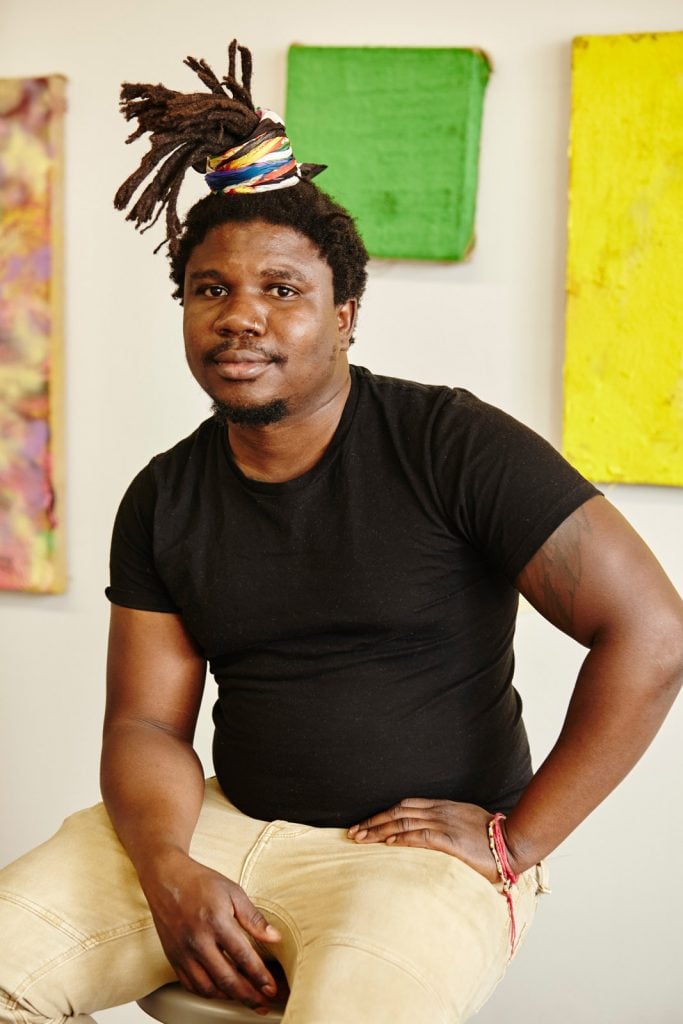

Tobi Onabolu

The Innovators is a five-part series of interviews with change-making art-world figures featured in the 2022 Artnet Innovators List.

For an artist at the forefront of the zeitgeist, whose work already commands imposing prices on the primary market, Alvaro Barrington brings a refreshing vulnerability to the way he talks about his life and work.

Born in Caracas, Venezuela, and raised by an extended family network between the Caribbean and New York, Barrington says his early experiences of community have made him who he is today. A rising star with an enviable exhibition history just five years out of art school, he has also embarked on a dizzying range of collaborative projects beyond the white cube—inviting other artists into his studio, putting on live music events, renovating a community basketball court, and now making plans to open a multipurpose art space in London’s East End. This summer, he extended his painting practice to performance trucks and a stage at Notting Hill Carnival, where he also commissioned architect Sumayya Vally to create a pavilion for revelers needing a break from the action.

Artnet News recently selected Barrington as one of its 2022 Innovators, a list of 35 professionals pushing the art industry forward. The conversation with him below is an expansion of Barrington’s entry in the Innovators List, in which he discusses the lessons of existentialism, finding inspiration in Nicki Minaj, and his secret to juggling the eight galleries that represent him internationally.

This summer, Barrington extended his painting practice to London’s Notting Hill Carnival. Photo: Timothy Spurr, © Alvaro Barrington, courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Tell me about day-to-day life in your universe. When you wake up in the morning, what does your day look like?

It depends on the day, but usually I wake up pretty early. The studio isn’t far away; a 30-minute walk through London Fields. No matter what my energy is like when I wake up, by the time I go through Columbia Road, I start to feel really grateful. I can’t believe I’m walking to my studio, about to make what I think is a good painting. Or maybe it’s gonna be a shitty painting. But I can’t believe this is what I get to do. There’s something about that moment—because I did retail, I did a lot of work at shitty restaurants, cafés, all of it, for years. Once that energy hits, I get really grateful, and by the time I hit the studio, I’m ready. My tear ducts fill up somehow. I never really cry—but I feel it.

Was there a point when you didn’t think this would be real?

Every day. Even when I’m making. When we were growing our hair back in the day, my friends and I would have this phrase, “the ugly stage.” When your hair is short, you can do all these things, such as waves, or partings. But the hair has this middle stage if you’re growing it out, where you can’t do any of those things, not even braids or dreads. It’s the stage when it’s not going right, and you’ve just gotta have faith. And that happens in the studio, maybe every hour. You just have to work through it.

There’s a lot written about your years up until school, then there’s this jump to 2017, when it’s all about London, starting with you graduating from the Slade School of Fine Art. Can you tell me more about that time in between—the 2000s and 2010s?

I was in school for 12 years. I was supposed to graduate in 2006, but in 2005 I transferred from Hunter [College in New York] to a city university, which was a lot more affordable. At that time I was much more focused on photography. I knew that I wasn’t prepared to graduate, because I had friends who were photographers doing amazing things, and I would look at my work, and I knew I wasn’t good.

One of the philosophies I admire is existentialism, because it gives me a lot of truth. Sartre talks about bad faith. Telling yourself something about yourself, which you hope for the world to validate, yet the world says, “no, you’re wrong.” A lot of people end up lying to themselves, thinking the world is wrong, and that’s where bad faith kicks in. The way I deduced that for myself was through basketball. “I’m a great basketball player,” I would tell myself. Then I would get on the court and somebody would bust my ass. I had two choices at that moment—I could live in bad faith and say, “that person cheated, the whole system is rigged,” or I could say, “I need to practice more.”

I’d go to class or a show and people would be dropping all these crazy terminologies that I didn’t know, and I thought, “maybe I’m just dumb.” Then I switched my major to philosophy, which I studied for three years. When I got back into art I realized, “you guys are all dumb, you’re just making up big words about bad art to make people feel like they’re dumb.” So I ended up doing a longer time in school, filling in the gaps of my knowledge.

Alvaro Barrington in his studio, August 2022. Photo: Timothy Spurr, © Alvaro Barrington, courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Let’s talk about Artists I Steal From, your 2019 show at Thaddaeus Ropac gallery of 49 artists who influence you. I love the honesty of it! Anyone who thinks they’re creating original work is really fooling themselves. Why was that an important concept for you to explore in curating that show?

[Senior global director of special projects at Thaddeus Ropac gallery] Julia Peyton-Jones was doing a studio visit and one of the things that came up was something that I do as a student, related to not being good enough. So how do you get good enough? You have to practice more, and study. For instance, you could see where Kobe [Bryant] stole Michael Jordan’s moves. Or you look at a Picasso and you can see Matisse. So we were talking about the artists that I steal from, and she said we should do a curated exhibition. It’s something I do a lot. I’ll go to the National Gallery and stare at a painting for 10 hours, breaking down how the artist made that work.

What are you currently working on?

Lately I’ve been making these paintings which think about this festival in the Caribbean, Wet Fete. I’m thinking about Patrice Roberts, a soca singer, and Nicki Minaj. I’m interested in how Nicki Minaj addresses men through her lyrics, finding pleasure in rap. There’s a long history in painting of men looking at women, so I want to consider this when painting these women [from the festival]. If you look at someone like Lisa Brice or Deana Lawson, there’s a way they look at Black women. There’s such tenderness and sensitivity, so their characters become full human beings. How can I, as a straight man, paint more fully formed women? So I’ve been listening to Patrice and Nicki a lot.

Alvaro Barrington, Splash / Hornimans (2022). Photo: Katie Morrison, © Alvaro Barrington, courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Your practice is often discussed in terms of collaboration—between various cultural influences and even between the eight different galleries who represent you globally. At what point does collaboration with others begin for you?

I’m an orphan, so I grew up in a community that had to collaborate and decide how to raise me. I became keenly aware of the many caregivers in my life, for example the aunt I’d see in the morning, and another aunt I would stay with at night. I was able to see and experience the truth that it takes a community to raise a child. And if one person didn’t keep up their end of the bargain, I knew that I would have to sleep on the street that night. I quickly became aware of the extremes of collaboration and community and how things can easily fall apart without it.

So I say today that my most expensive mistakes are when I don’t rely on community, even in the studio. For example, I have a shoulder injury right now, partly because we were in the studio with a cement work. There were three others around me but I was like, “I got it, I got it.” I lifted [the cement piece], and I tore a muscle in my shoulder, so I’ve had to go to physical therapy for a year to fix it!

In working with multiple galleries at once, you seem to have successfully shifted the traditional artist-gallery power dynamic in your favor. What’s your secret to this way of working?

It’s about honesty and sincerity, and not lying to people. Oftentimes it gets misquoted as some game I’m playing.

One of the “emperor’s new clothes” philosophies the art world took on was the neutrality of the white cube. But the white cube is not neutral. A location has energy and history. It can be really inviting and exciting to some people, and not for others. All of these things play out even before you put something on the wall. So when I do a show, I try to take in as many of those considerations as possible.

For example, collectors know Sadie [Coles] for working with certain artists within a certain vein, therefore when I show my work there, my art doesn’t have to work as hard. The gallery gives me that social capital and credibility. A gallery such as Corvi-Mora has people like Lynette [Yiadom-Boakye], who paints Black people without scars. It’s often about seeing who the gallery is.

This way, I can gain a greater understanding of how I can become a better artist. Laura Owens, who introduced me to Sadie, is to me one of the most brilliant painters working today. Coming onto Sadie’s program is being in conversation with artists who help me figure myself out as an artist.

It also comes back to being an orphan. In my childhood, I saw it as a choice. I could be really upset that I didn’t have my Mum anymore, or I could be so grateful to be able to learn tenderness from this aunt, problem-solving from that aunt, and so on. I got to pick how to become a better person from eight different influences in my life.