Galleries

Dealer Nicholas Logsdail on Highlights From 50 Years of Lisson Gallery, From Yoko’s Cryptic Letter to Marina’s ‘Groovy’ Room

How an accidental gallerist became an international success story.

How an accidental gallerist became an international success story.

Eileen Kinsella

When Nicholas Logsdail launched his gallery on London’s Lisson Street in 1967, he saw it as a short-term way to support his artist friends and fellow students at the Slade School of Fine Art. He envisioned the first show—and that was about it.

Fifty years later, Lisson Gallery is going stronger than ever, boasting a lengthy—and increasingly global—roster of groundbreaking artists from all five decades in business. The gallery is celebrating its milestone anniversary with an off-site London show titled “Everything at Once,” launched in partnership with the independent arts group The Vinyl Factory. It opens at Store Studios, October 5-December 10, and is accompanied by a hefty 1,000-page book that draws heavily from the gallery’s archives, titled ARTIST | WORK | LISSON.

In the late 1960s, Logsdail was caught by surprise when a Slade administrator told him he was not welcome back at the school since his focus seemed to have shifted primarily to running the gallery, as opposed to his studies.

“At that moment I realized that I had to do another show and another show after that,” says Logsdail. “It was a sense of far more urgency than I had ever had when I was studying. I got very plugged into what was going on in the art scene all over London.”

Even though there was never an explicit plan to compile an archive, Logsdail has “always been very careful about building the gallery around a particular style,” says Greg Hilty, Lisson’s curatorial director since 2008. “It seemed very natural to keep material, especially because many of the artists he started working with very early in their careers.” Sol Lewitt and Dan Graham were emerging artists when Logsdail began showing them, as were later generations of artists, including Anish Kapoor, Richard Deacon, Tony Cragg, Ryan Gander, Haroon Mirza, and Wael Shawky.

In the lead-up to the first show, Logsdail tried to settle on a name for the gallery. “People were trying to come up with all sorts of catchy names and none of them worked, and I didn’t want to use my name,” he says. “A month before opening it became apparent that it was very urgent to give this space a name. I was walking down Bell Street and as I turned the corner onto Lisson Street on my way to the Slade, it hit me like a thunderbolt. There was the name: Lisson Street. Of course it’s Lisson. That stuck in my head and I tried it out on my student friends. A name with a double meaning—it is what it isn’t and it isn’t what it is. If it was “listen” that would be very cheesy. So that was it, and 50 years later it’s a name that has served us well.”

With the help of some of the gallery’s archival photos dating back across the past five decades, Logsdail walked us through some notable moments in the gallery’s long, illustrious history.

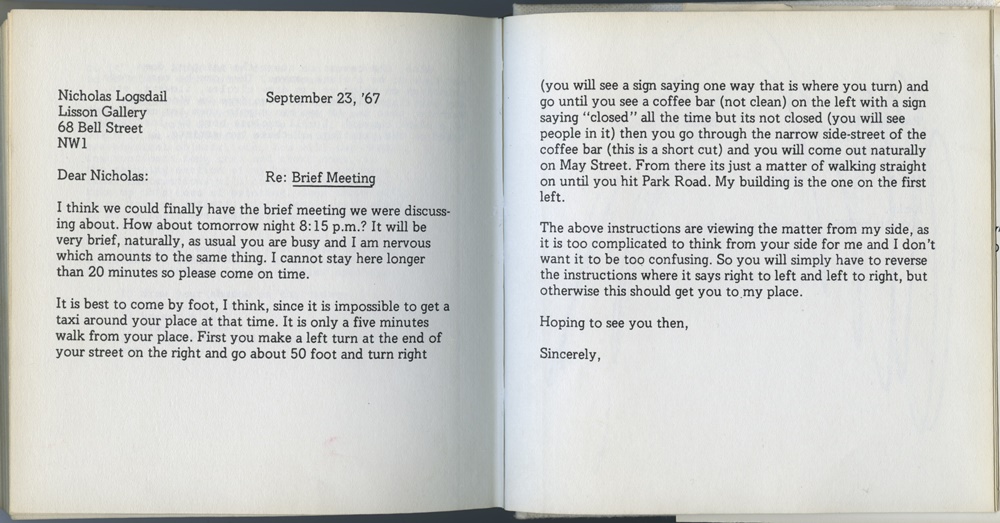

A letter from Yoko Ono to Nicholas Logsdail inviting him to her London studio. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

“Someone introduced me to Yoko Ono. She said, ‘You’re the guy who just opened a gallery. Can I come have a look?’ and I said, ‘Of course you can,’ and she said, ‘Maybe you should look at what I’m doing first.’ Then I got this letter, which was reproduced in her book Grapefruit. I literally did follow her instructions and, with a little bit of difficulty, found my way there, but I got lost and was 15 minutes late. Everything was painted white—it was rather grand.”

Marina Abramovic, White Space (1972), a sound installation consisting of amplified sound from a blank magnetic tape within a circular, white-papered space. Instructions read: “Enter the white space. Listen.” Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

“You entered the space, there were some cushions, and you could sit down and relax a bit. Basically all you were listening to was white noise, so the space was empty and silent, and there was a 1960s tape recorder running, which recorded the silence. It was a sort of John Cage-like experience.”

How did visitors react? “Oh mostly nonchalance some people said, ‘Oh groovy, man.’ That was language from that era that’s no longer in use.”

“As Deacon’s work began to mature, one of the most interesting characteristics of it was dealing with both the interiors and exteriors of forms. It alluded to forms in the real world. This is almost like a shoe, like a stiletto. It reflected a way of thinking that was post-conceptual and post-minimal. You couldn’t go back into that territory because that was done. What you could do was go into the idea of form and space as metaphor.”

“Anish’s first pigment works very much got my attention. I walked into his studio and on the floor were his geometric and biomorphic forms in the most exquisitely beautiful powdery color which turned out to be pure pigment. I thought that these were really quite remarkable in their simplicity, but they felt completely fresh and new. It’s very hard to find adjectives for it because I’m trying to avoid the ‘S’ word—spiritual. I started working with him very shortly afterward. We struck up a good friendship.”

Outside of Ai Weiwei’s first exhibition at Lisson in 2011. The gallery supported the “Free Ai Weiwei” campaign through posters of Ai and excerpts from his writings, such as “Words can be deleted, but the facts won’t be deleted with them.” Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

“We had this enormous poster made for the front of the gallery. It turned out to be illegal because we didn’t have a license for it, so we had to take it down when the police came around. But it had already been up for two weeks, so it had done its job. As you can see, the whole street is full of people, there must have been 2,000 people there. It did an excellent job reaching Chinese authorities, which ended with him being released. A big part of that effort came from the UK but it was also world diplomacy.”