Galleries

Olfactory Art Dealer Andreas Keller Already Knows How to Sell to Clients Looking for Rare Perfumes. But Art Collectors? That’s New Territory

The dealer's new gallery isn't just about the rosy side of scent experience.

The dealer's new gallery isn't just about the rosy side of scent experience.

Janelle Zara

In New York’s Chinatown, the Henry Street gallery Olfactory Art Keller specializes in scent-based work. At its last show in July, artist Maxwell Williams unveiled “CNC Musk Factory,” a suite of new fragrances inspired by BDSM themes of shame, torture, and bodily fluids. His “Constraint Forever” series, also making its debut, lined the walls with swathes of vegan leather in transparent cases, which visitors could sniff through openings in the Plexiglas.

The works had titles like Cuir Daddy, Futanari, and Anal, and pungent odors to match; there were also sprays with names like Vanilla Shit and Pisssss Baby that I couldn’t bring myself to try. But during the opening, when a gallery visitor braver than me spritzed himself with a work called Cum Party, he was nice enough to let me smell his wrist. It was more pleasant than I expected, like a masculine cologne; I pictured a Victorian study with a dark wooden desk, tinged with the faint musk of something else. The guy told me that he liked it too, but described it in terms of its earthy, herbal notes. I remember the use of the word “vegetal.”

During the opening of Williams’s BDSM-themed exhibition, the artist performed a ritual of public shaming. Photo courtesy Olfactory Art Keller.

For gallery founder Andreas Keller, conversations like these are among his favorite parts of the job. “I’m interested in whether there’s an objective truth to what something smells like,” he told Artnet news. “Do you smell what I smell?”

When visitors debate, they illustrate the uniquely personal nature of olfactory experience. “It connects to memories in your life that are sometimes very emotional,” Keller added. “There are different degrees of sensitivity between people, where some say it’s too strong and others can’t smell it at all. ”

To smell the new works in Maxwell Williams’s “Constraint Forever” series, visitors would remove the foam stopper and sniff through the opening in the plexiglass case. Photo courtesy Olfactory Art Keller.

The first-time gallerist, who holds PhDs in genetics and philosophy, opened Olfactory Art Keller in February 2021 after losing interest in academia. In a previous life, he had studied smell habits in fruit flies and humans at Rockefeller University, taught at Columbia, and published a book, Philosophy of Olfactory Perception, in 2016.

Despite having no art-world background, he was interested in opening a gallery that would offer a full-bodied sensory experience. “Everything now moves towards a visual experience of the world,” he said, describing the way television, the Internet, and social media alienate us from reality. “I think smell is a marker of authenticity—it allows us to engage in ways that visual and auditory stimuli do not.”

Leasing a small storefront on Henry Street, ideal for both its proximity to other galleries and pandemic-era pricing, Keller inaugurated the gallery with a solo exhibition by artist M Dougherty titled “Forest Bath,” a riff on the Japanese concept of shinrin yoku, or a therapeutic trip to the woods. Sculptures made of wax and mycelium were infused with the scents of different forest elements, including cedar, soil, and grass, which in aggregate made up the woodland immersion.

Scented sculptures from M Dougherty’s “Forest Bath” solo exhibition. Photo courtesy Olfactory Art Keller .

“Passerby and gallery guests are invited to sit and breathe in the forest,” Dougherty wrote in a statement. Under the early 2021 constraints of the pandemic, the artist devised a kind of curbside delivery of the exhibition, pumping the scent out onto the sidewalk and projecting an image of a tree onto storefront windows.

Exhibitions at Olfactory Art Keller vary between conceptual practices like Dougherty’s and Williams’s, to those of more traditional scent-makers, like those in the spring 2021 group show “Perfumers Gone Wild.” Seven professional perfumers, temporarily freed from the conventions of the fragrance industry, each produced bottled scents to evoke abstract sensations: hope and hopelessness, religious ritual, experiencing the sculptures of Richard Serra.

That dichotomy between the conceptual and traditional reflects the gallery’s divide between two distinct groups of collectors. On the one hand, there are “the fragrance collectors who are interested in finding rare and unique scents,” Keller said. On the other, there are the art-world collectors, who are decidedly more difficult to convince.

“Scent is difficult to control,” the gallerist said. There’s fear of odors spreading and contaminating other works, which is fair—following an early show by artist Camilla Nicklaus-Maurer, Keller had trouble getting the smell of banana out of his own clothes. These days, however, he’s equipped with a pump that can turn over the air inside the gallery within an hour. Overnight, he also runs an ozone generator that destroys airborne molecules, leaving him with a clean slate in the morning. But for the traditional art world, olfactory art also poses questions of longevity. “Smells won’t last 100 years,” Keller said. “From a preservation or collecting standpoint, that generates some problems.”

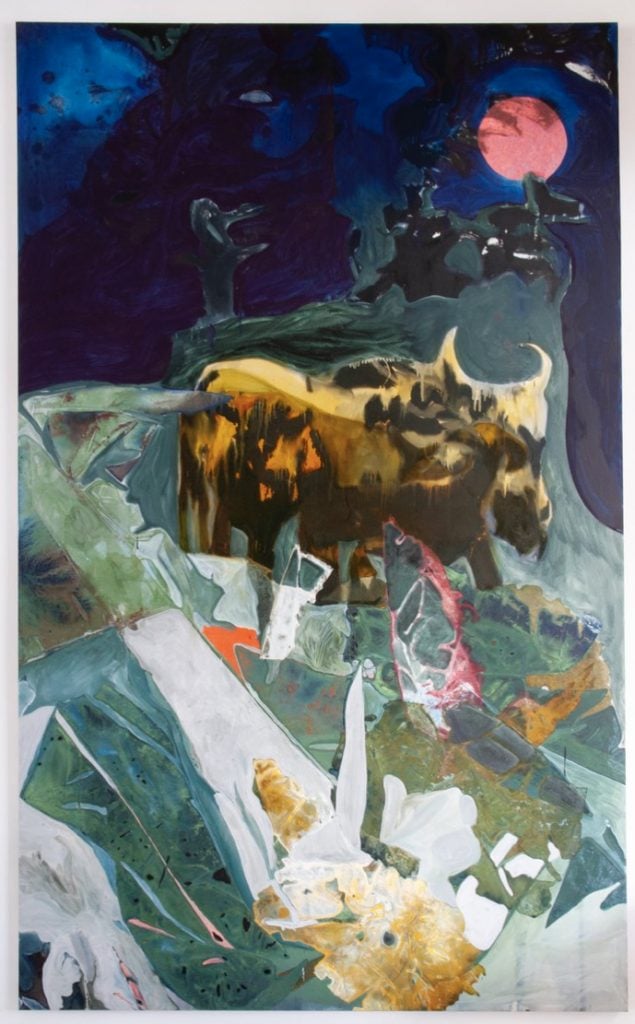

Keller’s willingness to show such uniquely challenging work has its advantages. “It’s very easy for me to find artists,” he said. “They’re eager to share their work, but don’t have a lot of outlets.” While viewers were prohibited from touching the works in Luiza Gottschalk’s solo exhibition at the National Museum of the Republic in Brasília this year, they were encouraged to explore the paintings in her concurrent Olfactory Art Keller exhibition with their hands. Their touch would release scents embedded in the paint, ranging from citrus to dry pastoral grasses. The pages of the accompanying catalog were treated with scratch-and-sniff technology.

Luiza Gottschalk, Cow’s Trail (2021), a touch-activated scented painting from the exhibition “Glade: To Touch Painting.” Photo courtesy Olfactory Art Keller.

Currently, Keller is reviewing submissions for a group show, “Portraits of Scent,” scheduled to open on September 8. He’s not looking for a bed of roses. “I’m always happy when an artist comes with unpleasant smells,” he said. “Imagine if you had only ever seen paintings of flowers.”