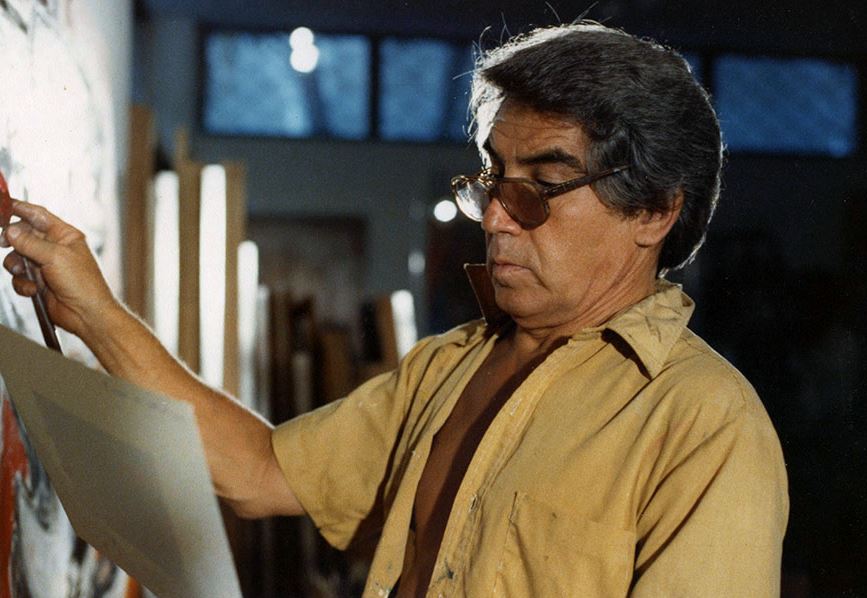

Image: www.oswaldovigas.com.

“My father hated art dealers,” says filmmaker Lorenzo Vigas, speaking of the Venezuelan painter and sculptor Oswaldo Vigas, who died in 2014 at age 90. He was talking with artnet News at the Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of São Paulo, while visiting the recently opened exhibition “Oswaldo Vigas Antológica 1943–2013.”

“Dealers want to pigeonhole you so they can more easily market your work,” Lorenzo continued, but, as revealed in the exhibition, the elder Vigas preferred to draw on a range of stylistic inspirations. The downside, his son conceded, is that without dealers, you might have no one to promote your work and maintain your legacy.

That task has fallen to him and the artist’s widow, Janine, who have formed the foundation that organized the exhibition, bringing together more than sixty paintings and a handful of sculptures drawn from the foundation’s extensive holdings. The show launched during the 12th edition of the SP Arte fair last week, which took place just across the street from the museum; both the fair and the institution are housed in buildings designed by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer.

The artist was at the heart of the Caracas art scene in the 1970s and ‘80s, when, Lorenzo recalled, that city was the capital of the Latin American art world, with many active artists, galleries, and institutions. Vigas had been friendly with giants like Max Ernst, Wifredo Lam, Fernand Léger, and Pablo Picasso during his years in Paris, and his work is represented in institutions throughout his native country as well as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, among others.

But his name is not well known outside the circles of experts in Latin American art, and the question is whether this exhibition, which makes a strong case for the quality of his work, will succeed in bringing the artist back into the public eye. Over the course of his six-decade career, Vigas indulged in Surrealist and Cubist idioms, mixing figuration and abstraction, with his work sometimes recalling the Constructivism of his near neighbor, the Uruguayan master Joaquín Torres-García. Elsewhere, the work evokes Paul Klee or Vigas’ countryman, Armando Reverón.

Oswaldo Vigas, Composición IV, 1943.

Photo: courtesy Oswaldo Vigas Foundation.

The exhibition has traveled to museums in Peru, Chile, and Colombia over the last two years, and the foundation is now in discussions with institutions in the US about future iterations of the show, curated by Venezuelan art historian and critic Bélgica Rodríguez and Katja Weitering, artistic director of the Cobra Museum of Modern Art, in Amstelveen, the Netherlands.

Miami’s Ascaso Gallery will show Vigas’ work this December, during the Art Basel in Miami Beach fair; that show will be organized by art historian Marek Bartelik, current president of the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art.

Born in Venezuela in 1923, the son of a doctor, Vigas studied medicine at the Central University of Venezuela before taking up art. Without any formal study, he won Venezuela’s 1952 National Fine Arts Prize, which included a plane ticket to Paris, where he enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts in 1953, also taking open classes at the nearby Sorbonne. He would soon show his work in the São Paulo biennial, Paris’ Salon de Mai, and in a show at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. His star rose further when some of his works were in a group show at the inauguration of the Venezuelan pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1954.

Oswaldo Vigas, Gesticulante, 1943.

Photo: courtesy Oswaldo Vigas Foundation.

He returned to Venezuela from Paris in 1964 and spent the rest of his life there, heading up the art department at the University of the Andes, in Merida, Venezuela, as well as instituting a film school. He would branch out from painting to sculpture, tapestries, printmaking, and ceramics during the 1970s and ‘80s.

Though he was a highly prolific artist—“he was always working,” his son recalled—only a few dozen of his works have come to auction. His highest public price is $221,000, fetched at Christie’s New York in November 2015 by the 1990 painting Paraíso inconcluso, which more than doubled its high estimate. Though fewer than ten of his works have broken the $100,000 mark to date, his market is rising—those top prices have all come in the last five years, after all.

Oswaldo Vigas, Duende Rojo, 1979.

Photo: courtesy Oswaldo Vigas Foundation.

That Vigas’ son is now helping to mind his father’s legacy makes the artist’s story particularly compelling, and, as it happens, familial dynamics are an interest of Lorenzo’s. Like his father, Lorenzo studied biology but left that field for the arts, also achieving striking success—in 2015, he became the first Venezuelan to win the Golden Lion for best film at the Venice Film Festival, for his debut feature, Desde Alla (From Afar), a drama that, he told Variety, engages his “obsession with paternity.”

Before his father’s death, Lorenzo Vigas shot the documentary The Orchid Seller, now in post-production, about the artist’s quest to find the first painting he ever sold. Over breakfast at a São Paulo hotel, he talked about the work ahead in establishing his father’s place in history. He described boxes and boxes of his father’s correspondence with other artists, which remain unexamined in storage, and acknowledged that because his father sold many paintings out of his studio, the foundation has been hard at work locating his canvases for inclusion in a catalogue raisonné.

Oswaldo Vigas, Festejantes, 2010.

Photo: courtesy Oswaldo Vigas Foundation.

He also shed some light on a formal turn in the artist’s work from his last decade, following a period of rest while recovering from a stroke, when he introduced new hues into his canvases, exploring lemon yellows, lime greens, and sky blues in works like Festejantes XVIII (2010).

The new colors indicate “his joy at being alive,” says Lorenzo, adding, “he was so happy to be working again.”

“Oswaldo Vigas 1943–2013” is at the Museu de Arte Contemporânea de São Paulo, through July 3, 2016.