The Art Detective

Shoptalk: Gallerist Paula Cooper on Her Enduring Relationships with Artists

'I’ve always liked challenging works,' she says in Part 3 of an expansive interview. 'I can’t help it.'

'I’ve always liked challenging works,' she says in Part 3 of an expansive interview. 'I can’t help it.'

Katya Kazakina

Shoptalk is an interview series about the experiences of women art dealers and industry insiders of various generations, as told to Artnet’s Art Detective columnist Katya Kazakina. Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access—subscribe now. Part 1 and Part 2 of Kazakina’s interview with dealer Paula Cooper were published last month.

Gallery hopping in Chelsea last Thursday—from Jordan Casteel at the Hill Art Foundation to Karma’s mobbed arrival on West 26th Street to Joel Shapiro at Pace and on, and on, and on—I ended up at Paula Cooper for Christian Marclay’s latest solo show.

Marclay, who’s best known for his iconic 24-hour video, The Clock (2010), is showing a recent work, Subtitled (2019), beneath the gallery’s vaulted ceiling, which is lined with wooden beams. The cavernous building on West 21st Street has been the business’s home since 1996, when Cooper was among a handful of pioneering dealers who relocated from roaring SoHo to desolate West Chelsea.

It was a prescient move. Chelsea has become the global epicenter of contemporary art. On Thursday, crowds spilled out onto the sidewalk at Gagosian’s down the block. The vibe at Cooper’s space was calmer but no less intense. One after another, a parade of museum directors and high-ranking curators paid their respects.

There was Lisa Phillips of the New Museum, and Anne Pasternak of the Brooklyn Museum, and Naomi Beckwith of the Guggenheim, and Kathy Halbreich, formerly of MoMA and the Rauschenberg Foundation. There were artist Joan Jonas and the Artforum publisher Danielle McConnell. My head was spinning by the time the Whitney’s Scott Rothkopf dropped by shortly before 8 p.m.

Christian Marclay and Paula Cooper at the opening of his new exhibition, Subtitled, in New York. Photo: Katya Kazakina

The scene was a reminder of the quiet but far-reaching power that Cooper, 86, wields in the art world. At the core of it all is her unerring eye and her profound relationships with artists. She was just 17 when she decided that she wanted to spend her life helping artists, who included her mother, a passionate Sunday painter.

Last month, as Cooper walked me through her apartment, she pointed out a small abstract work on a comic book page, with the phrase “Toc Toc” visible. “That’s Christian,” she said about Marclay. “Every single thing he does has some audio reference.”

Marclay’s current show is no exception. His video is all about subtitles in film. His works on paper, displayed in the smaller gallery, features speech bubbles, ears, and explosions.

Marclay and Cooper have been working together for decades. They met at some point in the early 1990s, and their conflicting recollections of exactly where and how include a performance by Peter Kotik’s S.E.M. Ensemble and Robert Gober’s Christmas party. “I was so intimidated and impressed by her,” Marclay told me.

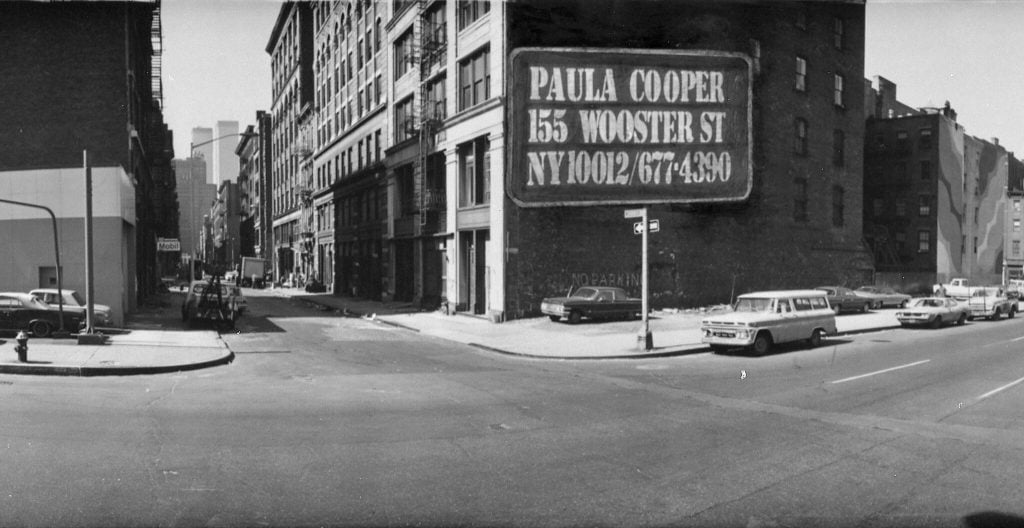

The Paula Cooper Gallery at 155 Wooster Street in SoHo in 1973. Photo by Mates and Katz, courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

Cooper was 30 years old—a young mother pregnant with her second child—when she opened her eponymous gallery, after spending more than a decade in the art world trenches, working as an assistant at the World House gallery uptown, meeting artists, and cultivating collectors. She briefly ran a small gallery (under her maiden name, Paula Johnson) in her townhouse across from Hunter College and then oversaw an artist cooperative, Park Place, downtown. Her gallery was born as a fully formed being, its aesthetic identity clear from day one.

The third part of my conversation with the legendary art dealer focuses on the artists she has championed. Part 1 explored her path to power, and Part 2 centered on the art trade. The interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

You played a key role in promoting Minimalism and conceptual art. What about it excited you?

I don’t think Minimal is really a very satisfactory term.

I’ve always liked challenging works; I can’t help it. Works that make you think and that are satisfying visually. Works that amaze you, that surprise you. It’s like, “Whoever would’ve thought of that?” It’s wonderment. It’s ineffable.

I remember when I first went to Walter [De Maria]’s studio, he just sent me in and closed the door. And there was this piece, Ball Drop, this tall wooden piece with an opening and there was a ball, and you put the ball in and it dropped. Wow.

Installation view of “Benefit for the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam,” Oct. 22–31, 1968, at the Paula Cooper Gallery, 96-100 Prince Street, New York. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery

It’s crazy to realize that these acclaimed artists, Walter De Maria, Carl Andre, Sol LeWitt, Lynda Benglis, were young emerging artists when you met them.

Lynda Benglis came to my little gallery and we became friends. It was 1964. She was going to Hunter College. Later she helped me for a while with secretarial stuff in SoHo. She wasn’t paying attention. All she was thinking about was her work. She was a riot.

How long did she last?

Probably a couple of months. Then we showed her for many years. She had her first show in 1969–70—up until the late 20th century. She had a one-person show practically every year with us. We are very close friends.

Between your Paula Johnson gallery and the opening of Paula Cooper gallery in 1968. You worked at Park Place Gallery. Can you tell me about this experience?

John Gibson formalized the organization of 10 artists — five painters and five sculptors —into Park Place gallery and enlisted financial support in the form of five backers. Before it was just a group that informally got together. And the agreement was that these people would give, I think it was $8,000 a year, and they would get a work of art by each artist, annually.

Oh my God, what a deal!

But remember $500 was a lot of money at the time.

The artists had started it themselves down on Park Place, and then they got him involved. By the time I got involved, they were on West Broadway. John called me and said he needed help and would I come and work at Park Place. So, I went and then he left, and I took his place. And that’s how I met Patrick Lannan and Vera List, two great collectors.

I also met artists with whom I continued to work through the present. Mark di Suvero, David Novros, and until last year, Bob Grosvenor.

Everyone was very surprised when you started working with Cecily Brown in 2017. How did it happen?

When she was very young and she first came here, she invited me to her studio. I thought she was a really good painter, no doubt about it, but my mind was elsewhere and she was doing these paintings of little copulating rabbits. I wasn’t particularly looking for any New York young artists.

Years go by. I saw her occasionally. She left Gagosian, and I guess a couple of years went by and then it just happened. She’s a really extraordinarily good painter, just a natural-born. She’s a very kind person, too. She can be too generous, perhaps, sometimes. I mean, all these people, “Oh, Cecily, I am doing a benefit show.” It is difficult for her to say no.

Installation view, “Cecily Brown: Death and the Maid,” on view a the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: Paul Lachenauer, courtesy of the Met.

How do you decide who gets the work by Cecily Brown? I’m sure people are lobbying you non-stop to get her work first.

Museums come first.

It’s interesting that you have continued working with most artists who left for other galleries.

Sometimes they left and came back, or they left, and we still do things together.

Like Rudolf Stingel? How did it happen that he left for Gagosian?

We were very good friends, but I always kept telling Rudi, “It’s going to happen, you’re going to be very successful.”

I think we met, we had lunch and we talked about it. I thought it would be good. There was over-enthusiasm in the beginning, and with their international outreach, there were perhaps too many shows. They had a negative effect on his market for a while.

But he obviously went along with it. How is his primary market now?

In our experience, it’s good. We always sell his work when we get his work.

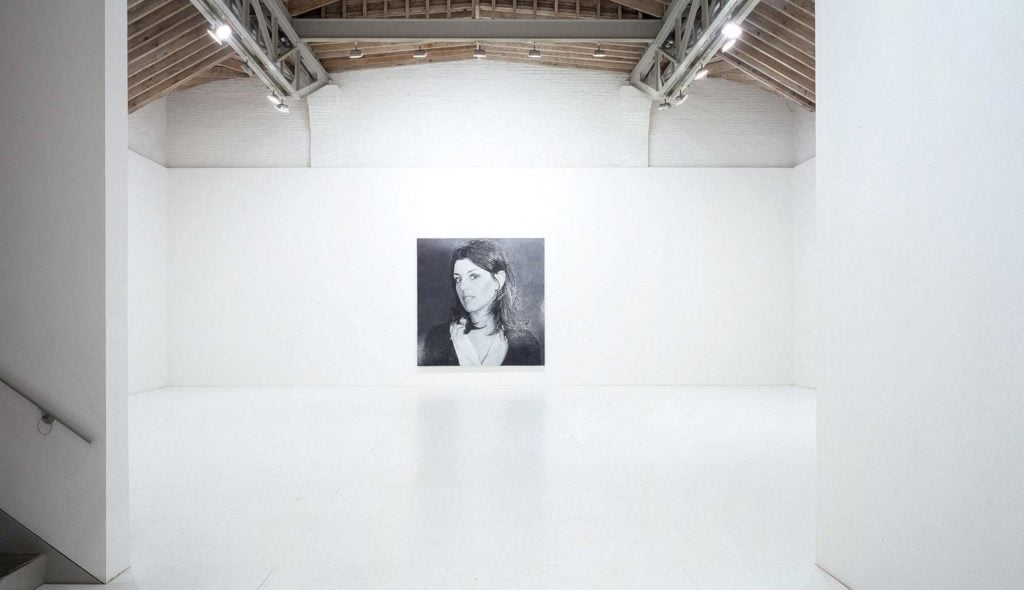

Installation view, Rudolf Stingel, Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, February 12 – March 12, 2005. © Rudolf Stingel. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Adam Reich

He painted you, right?

Twice. The first was from a photograph by Mapplethorpe. He owns that one. And the other one was from a snapshot someone took, and it’s in the collection of Pinault.

It’s very sweet. But he did pictures of friends like that wonderful sculptor Franz West. And he did portraits of himself at different ages.

You still work with Joel Shapiro, who just opened a show at Pace?

Over several years, he talked to me about it all the time, whether he should go to Pace or not. He’d say, “Should I go, or shouldn’t I go?” I finally said to him, “For Christ’s sake, Joel, go! Just do it. You’re driving me crazy.”

And you know what Joel did? He brought a piece of sculpture as a gift to me, as a farewell. He delivered it himself. And we’ve worked together ever since. We had a beautiful show three years ago.

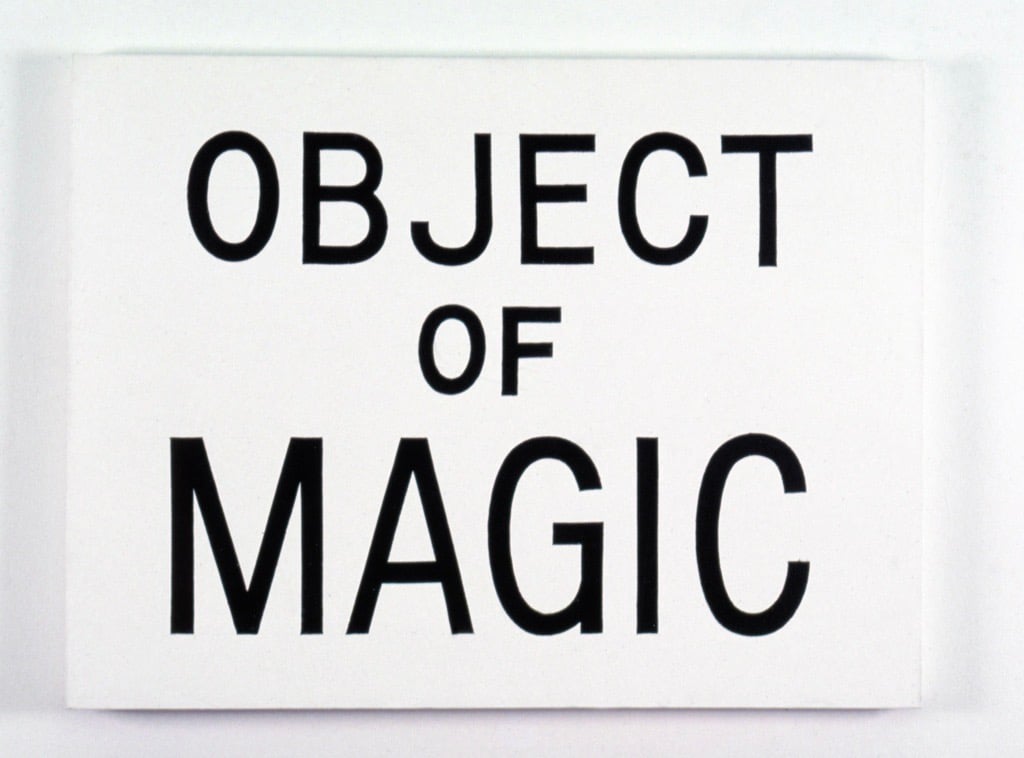

Jonathan Borofsky’s Object of Magic (1989). Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery

What happened to Jonathan Borofsky? His paintings and sculptures were so popular in the 1980s and then he just disappeared.

He was so popular, but he didn’t want to be part of the art world. He wanted to be in his studio, to be quiet and peaceful.

He is a loner. He lives in Maine. He sends me pictures of the sunrise on the beach. He goes to his studio early in the morning from his house. He’s making work. And he’s married to a lovely woman now. We have a nice friendship. I show his things every once in a while. As does Jeffrey Deitch.

But he basically killed his career, right?

Sort of, yeah.

Does this make you sad?

I respect it because it’s so much a part of who he is. It’s not like I think he made a huge mistake and ruined his life.

I think he’s going to come back, too. We are having a pop-up in Shanghai in November and our director selected an early painting of his that she really wanted to be in the show. It will be the first thing you see when you enter. Three words on a canvas: “Object of magic.”