Auctions

Phillips’s $114 Million Contemporary Sale, Led by Peter Doig, Brings the Art World Back to Earth

Doig, Picasso, and Basquiat were the stars at the house's solid, un-flashy sale.

Doig, Picasso, and Basquiat were the stars at the house's solid, un-flashy sale.

Henri Neuendorf

The art world seems to have sobered up after Wednesday night’s paradigm-shifting sale of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi for $450 million at Christie’s.

At its fall evening sale on Thursday, Phillips achieved a solid total of $113.8 million, falling squarely within its presale estimate of $90—123.5 million, with a 96% sell through rate and 40 of the 44 total lots sold. Indicative of market optimism, and perhaps a reflection of climbing equities markets, the typically conservative auction house guaranteed about 40 percent of the lots on offer. (In May, it guaranteed roughly 33 percent.)

Starting a little late, at 5:15 p.m., the sale got off to a roaring start with the fifth lot, Pablo Picasso’s work on paper Portrait de femme endormie III (1946). After a protracted bidding war between two telephone bidders, an Asian buyer on the phone with Phillips specialist Ken Yeh came out on top when the hammer dropped at $8 million ($9.3 million with fees)—nearly nine times the high estimate.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait de femme endormie III (1946). Photo courtesy of Phillips.

The top lot of the night, Peter Doig’s Red House (1995—96), was touted as a possible record breaker after the house set Doig’s auction record in May. It fell short of that achievement, but did sell close to the high estimate, for $21.1 million, amid applause. The work went to a telephone bidder on the line with Phillips’s co-chairman, Cheyenne Westphal.

In the past, Phillips tried to compete with the big two houses—Sotheby’s and Christie’s—by paying generous guarantees to consignors, a strategy that too often resulted in losses. In recent years, however, Phillips has shifted its approach by investing in personnel, hiring a slew of high-profile auction professionals from its rivals (with the support of its Russian backers, the Mercury Group).

Just less than a decade since the Russian company took over, the strategy is starting to pay off, said Jean-Paul Engelen, Phillips’s co-head of 20th century and contemporary art, in an interview with artnet News at the auction preview. “By building a new team, we’re also bringing in new relationships,” he said. “This is where our sale is different from three or four years ago. We have these types of works now” he added, gesturing toward blue-chip works by Peter Doig (estimated at $18—22 million), Franz Kline ($10—15 million), Cy Twombly ($6—8 million), Rudolf Stingel ($5—7 million), and Jean Michel Basquiat ($3.5—4.5 million).

Targeting the upper-to-middle segment of the market appears to have been an effective strategy. “For most collectors, $60 million paintings aren’t realistic—they collect work between $500,000 and $5 million,” he said. “So that’s where we focus our energy. For us it’s a measured approach, we don’t like to feed the beast.”

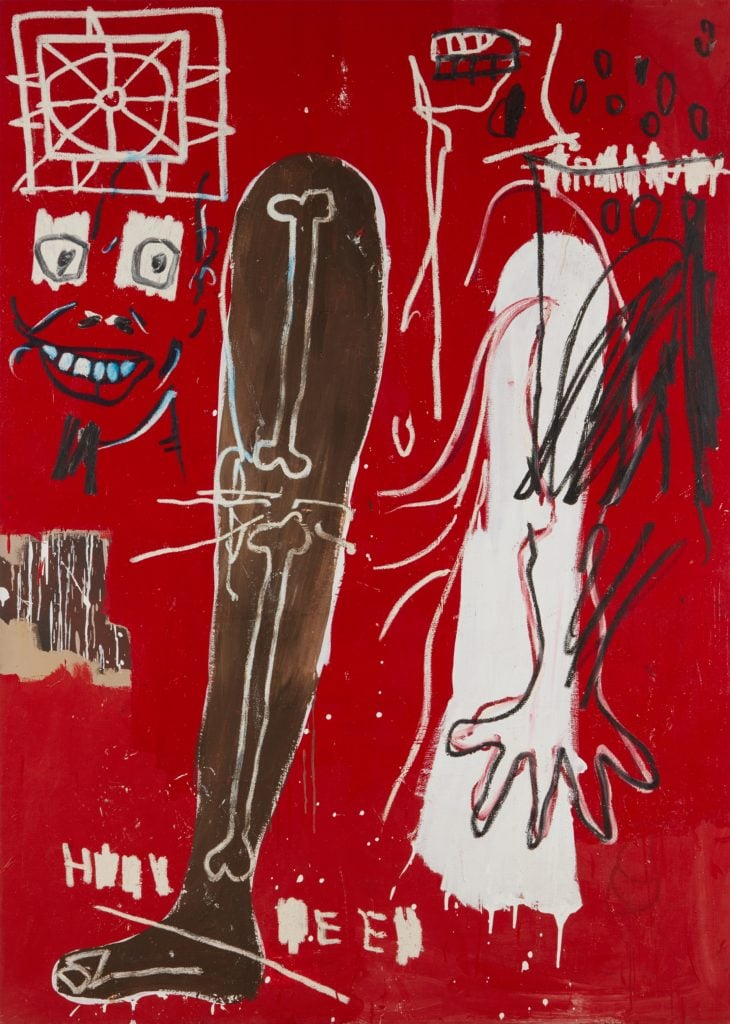

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Halloween) (1983). Photo courtesy of Phillips.

Flipping through the catalogue, it’s clear that Phillips has worked to expand the breadth of its offerings. Although it typically markets itself as a boutique contemporary art house, it won some superb modern sculptures and works on paper by Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Henry Moore from the collections of Betty and Stanley Sheinbaum and Anne Marie and Julian J. Aberbach.

Franz Kline, Sawyer (1959). Photo courtesy of Phillips.

Records were set in the Latin American segment for Carmen Herrera’s Untitled (Orange and Black) (1956), which sold for $1.17 million, and Hélio Oiticica’s P 31 Parangolé, cape 24, Escrerbuto (1972), which sold for $615,000.

The Franz Kline, which was the second-highest estimated lot of the evening, performed under expectations, changing hands for $9.9 million, just below the low presale estimate of $10 million. The bargain-hunting buyer in the room that placed the winning bid also took home the next lot, Joan Mitchell’s Untitled (1964) for $3.6 million.

Later, Cy Twombly’s Untitled (2004) landed right in the middle of its $6—8 million presale estimate when it sold for $7.5 million. Meanwhile, Rudolf Stingel’s Untitled (2012) performed similarly, selling for $6.3 million, comfortably in the middle of it’s $5—7 million estimate.

Cy Twombly, Untitled (2004). Photo courtesy of Phillips.

Consigned directly from the estate, a large red Basquiat painting from 1983 was bought for $4.2 million by a bidder in the room.

On the other end of the scale, two works by Sigmar Polke failed to sell, as did an abstract Joe Bradley painting, and a large Mike Kelley painting of a genealogical chart.

Speaking to artnet News after the sale, Phillips CEO Ed Dolman said he was “absolutely delighted” with the result. “Although this shows a small incremental step forward in comparison to the total from this time last year, in terms of the quality of the sale and the mix of the sale and how it was presented we thought we made a giant step forward,” he said.

“We’re all in awe of the Leonardo last night, behind that Christie’s had a solid, but not spectacular, sale, which shows the market is there, and we’ve carried that on tonight,” Dolman added. “The art market and stock market have been in lock step for a while, and the continued resilience of the stock market gave us confidence. But so did the quality of the things we’re offering. I think the art market is in good robust health.”

The sale was not flashy or headline-grabbing, but it was reliable and solid in a way that’s indicative of Phillips’s ongoing development: quietly and contently soldiering on amid an increasingly surreal market.