Galleries

‘Pier 54’ Bridges New York’s Renegade Past and Its Gentrifying Present

With plans to turn Pier 54 into a park, an art show revisits grittier times.

With plans to turn Pier 54 into a park, an art show revisits grittier times.

Ben Davis

In the first week of November, High Line Art opened an understated but adventurous art show at a pop-up space on 11th Avenue and 20th. Dubbed “Pier 54,” the show is something of a big deal in that it’s the first endeavor by the curatorial wing of the High Line that is staged at a space beyond the elevated park. It consists of 27 artists’ tributes to the titular pier, which, though currently being used as an events space, is nonetheless a decaying post-industrial White Elephant, slowly lowering its trunk into the Hudson River off 13th street.

Then, this Monday, a bombshell announcement abruptly turned the words “Pier 54” into big news—real news, non-art news. That is, media titan Barry Diller revealed that New York City would get a new park, a $170-million, amoeba-shaped island on the site of Pier 54 (to be rechristened Pier 55) with an amphitheater and three new performance spaces. The proposal was greeted with pleasure—who, after all, doesn’t like new parks?—but also immediate questions: Does the city really need three new outdoor performance venues? And why is the proposal being presented as a fait accompli, besides the fact that a billionaire is willing to bankroll the results of an “informal competition” that he himself orchestrated?

Rendering of proposed “Pier 55”

Image: Courtesy Pier55, Inc. and Heatherwick Studio

It so happens that Diller and his wife, wrap-dress mogul Diane von Furstenberg, are also the High Line’s biggest donors, often credited (or criticized) with finalizing the transition of the once-gritty Chelsea/Meatpacking district into the cluster of perfumed boutiques, upscale residential condos, and mega-galleries that it is today. Though the news about the pier’s future coincides with the exhibition that is in dialogue with its past, Cecilia Alemani, the director of High Line Art, tells me that there is no connection between the two events. “Hopefully our show will be seen as an attempt to preserve the great memories surrounding the waterfront,” Alemani said.

And indeed, the exhibition “Pier 54″ does not read as propaganda for Diller’s voluptuous pet project, quite the contrary. It seems like an elegy for the time, now passed, before the contemporary era of public-policy-by-billionaire-decree.

In keeping with a current curatorial vogue of looking back at past golden moments in the art world, the show pays homage to the 1971 show “Pier 18” and revisits the heady flowering of Conceptual art. In organizing that show, the great artist-curator Willoughby Sharp invited 27 big shots of the by-then-crystalized Conceptual movement to offer instructions for fleeting acts of art to be staged on Pier 18 in Lower Manhattan. The results were photographed in gorgeous black-and-white by the team of Harry Shunk and János Kender and yielded some wonderful fruits, most famously John Baldessari‘s image of his fingers framing views from the pier, a metaphor for the mind’s ability to reconfigure life as art.

John Baldessari, Harry Shunk, Janos Kender,

Hands Framing New York Harbor, 1971

For her response show, Alemani seized on the now-glaring deficiency of “Pier 18″—that it was an all-male affair—and asked 27 female artists to come up with their own proposals for the abandoned expanse of Pier 54 over the summer in 2014. Photographer Liz Ligon plays the Shunk/Kender role here, offering a series of crisp black-and-white documentary photos that are, in the Conceptual style, the actual artistic product. The resulting series of works by contemporary-art worthies ranging from N. Dash and Liz Magic Laser to Emily Roysdon and Aki Sasamoto, is well worth going to see on account of the wit of the projects as well as the glimpse they provide of the evocatively forsaken environment, soon to be no more than a ghost haunting Diller’s uber-park.

Installation view of Pier 54, 2014. A High Line Commission.

Photo: Timothy Schenck. Courtesy of Friends of the High Line

For her contribution, Sharon Hayes turned the pier into a wistful feminist billboard, having friends write the words “Women of the World Unite, they said” in massive letters on it (Ligon snapped the resulting spectacle from a helicopter). Jill Magid penned a series of postcards to each of the original “Pier 18″ participants, like this one to Gordon Matta-Clark: “Dear Gordon: I am on the pier but there is nothing left to remind me of you…” She held up the resulting works against the disheveled landscape and photographed them. Carol Bove, in a tribute to the bemused good spirits of it all, simply invited all of the “Pier 54″ artists to a jolly outdoor picnic on the pier.

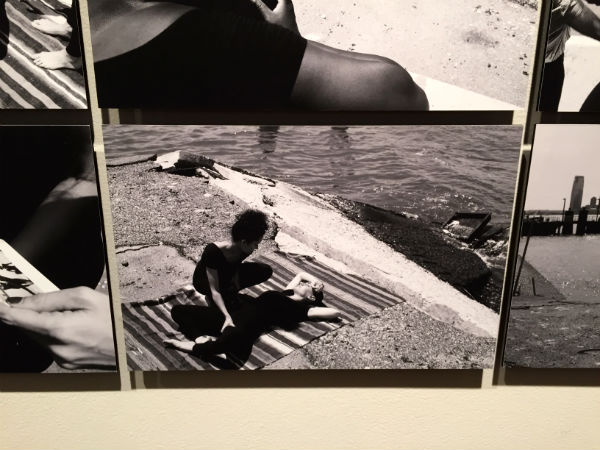

But the work that, for me, stands out comes from Xaviera Simmons. She operates on two levels at once: the abandoned piers’ lingering reputation as a spot for gay hookups, and the tradition of experimental dance culled from everyday life pioneered by the likes of Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown, contemporaries of the Conceptual experimenters of “Pier 18.” Simmons used documentary photos of New York’s racier past as a “score” to create a new series of photos featuring female dancers. Somehow at once artfully contrived and awkwardly intimate, Simmons’s images seem to ask: How do we appreciate today the nothing-to-lose moment of “Pier 18”? As a tradition to be reclaimed? As a challenge to overcome? Or as something accessible only as historical reenactment in a sanitized, corporatized present?

Detail of Xaviera Simmons’s series in “Pier 54”

Photo: Ben Davis

As Pier 54 gets transformed into Pier 55, I’m reminded of the direct connection between New York’s experimental art scene of the 70s and the city’s transfigured character. The political and financial shocks of the 60s and 70s unleashed a great explosion of artistic energy, but also signaled a terminal stage of New York’s deindustrialization. Soho, then a withering hub of the light industry called the “Cast Iron District,” was the favorite hangout of struggling artists, and its vast, raw spaces made much of the era’s ambitious experimentation possible. Avant-garde godfather George Maciunas faught to have the city legitimize artists’ anarchic co-ops. But his ultimate victory had a perverse effect: By putting their rebel cool on the books, it touched off the wave of artist-branded gentrification in Soho, a process that has now been institutionalized, instrumentalized, and imitated the world over, always inevitably pushing out the artists.

“It seemed in 1969… that no one, not even a public greedy for novelty, would actually pay money, or much of it, for a Xerox sheet referring to an event past or never directly perceived, a group of photographs documenting an ephemeral situation or condition, a project for work never to be completed, words spoken but not recorded,” the critic Lucy Lippard once wrote. To her chagrin, she was wrong. Collectors found ways to love Conceptual art’s head games. Today, in a Manhattan almost completely turned over to the triumphant millionaires, maybe we can push the lesson a step further and see Conceptualism’s legacy in another light, as having predicted the idea of art engineered to be fleeting because artists themselves are not meant to inhabit the world it creates.

“Pier 54″ is on view at 120 Eleventh Avenue at West 20th Street, through December 13, 2014.