Art Fairs

Punk Rock Spirit Gives the Sprawling Portland Biennial a Much-Needed Edge

Its "leftist Libertarianism" shows through.

Its "leftist Libertarianism" shows through.

Maxwell Williams

On July 10, a cool but sunny morning, a group of four journalists and our press handler booked it across Northern Oregon to Astoria, a quaint town on the mouth of the Columbia River known for its treacherous waters. When we arrived, New Delhi-born, Portland-based artist Avantika Bawa let us into the 1922-built Astor Hotel to show us her piece in Disjecta’s Portland 2016 Biennial, a scaffolding 20-feet high in the former hotel’s dilapidated dining hall, painted gold, and lit dramatically.

“When they were sending images of spaces available in the biennial, I saw this one, and wrote them a long email saying why I would be perfect for this space.” Bawa would later tell us over fried oysters topped with mint jelly and cream cheese. “I fought for it.”

Avantika Bawa’s installation. Courtesy of Maxwell Williams.

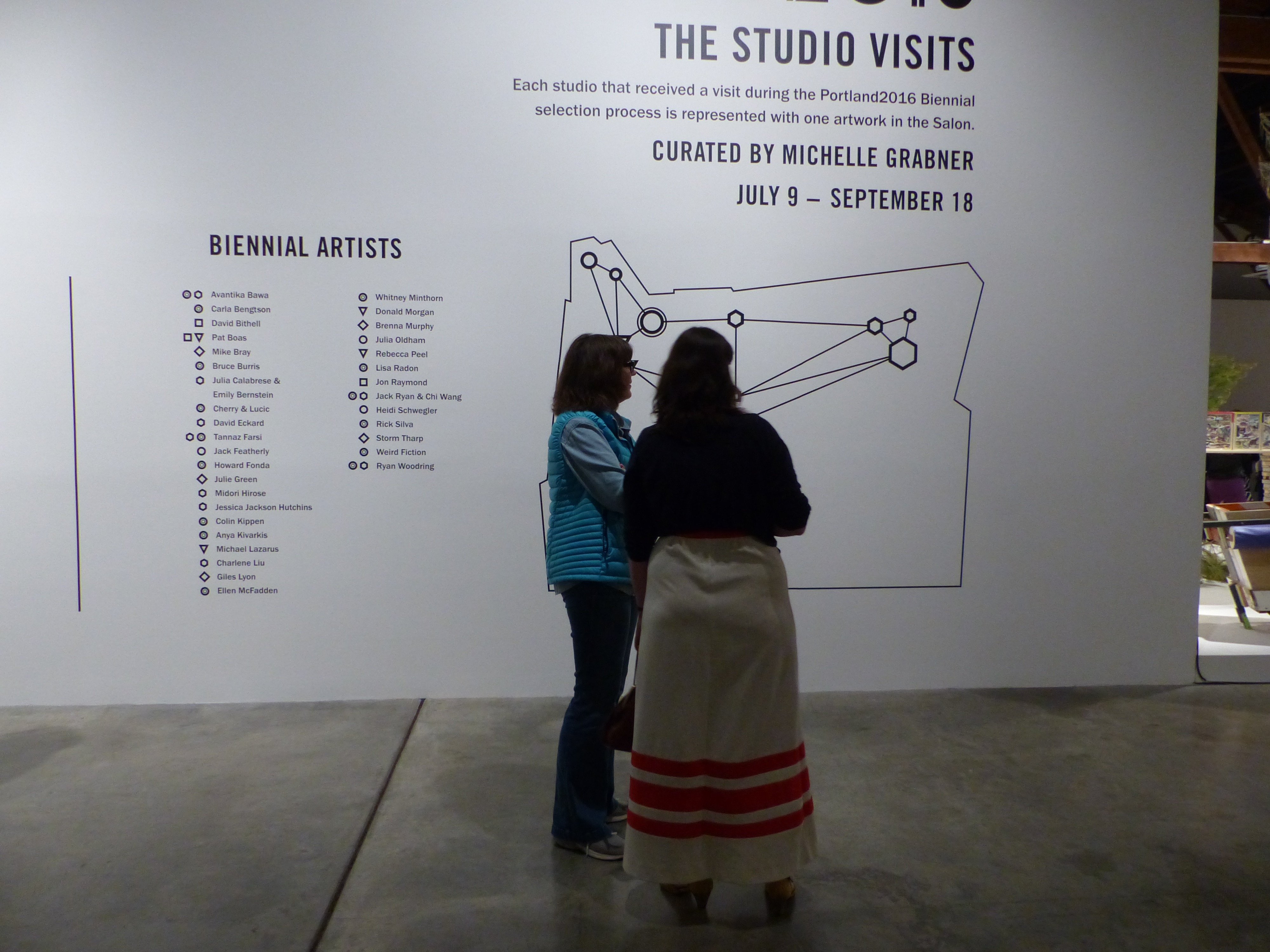

Bawa’s site-specific work is an approximately one-and-a-half hour drive from Portland, and travelers cross into Washington State for a spell before following the Columbia to the most Northwestern point of Oregon. In this, the fourth iteration of the current state of the Portland Biennial is actually something of a misnomer. Curator Michelle Grabner has expanded the show from a Portland locus to a statewide situation, connecting cities like a game of cat’s cradle.

Still, unlike the Hammer’s Made in LA Biennial this year, which favored positioning location as a moot point, the Portland Biennial cannot escape its regionalism. “Regionalism is a concept; it’s not an aesthetic,” Grabner told me standing outside the Ace Hotel in Downtown Portland. “It’s a political, social entity. It’s not a style; it’s more an anxiety than anything.”

This anxiety seems to come partly from the isolated nature of Portland, a city of less than a million inhabitants, met with a dash of state pride, and a general punk rock reluctance to conform to the artistic status quo.

Salt the Goat. Courtesy of Maxwell Williams.

Unpredictably, this is to the show’s credit. Some of the best presentations come from the most radical contributions Portland has to offer. Let’s look at Project Grow, for instance. It is an art space that doubles as a studio space that triples as an urban farm, giving art and gardening opportunities to adults with developmental disabilities. Portland-based artist Colin Kippen’s pearly spray-painted concrete confabulations of food packaging fused with broken garden tools looked lovely in the gallery. In the back, a man named Ricky in an Oregon Ducks t-shirt sat at a loom, making a rug, while a goat named Salt climbed in through a window, hoping we brought snacks.

Cherry and Lucic. Courtesy of Maxwell Williams.

At Cherry and Lucic, possibly the most Loki-esque space I’ve ever encountered, Eleanor Ford, one-third of the trio along with John Knight and Kyle Raquipso, went on a screed about the biennial system in general, Disjecta in particular, the fact that they had “applied to the Biennial as a joke—Michelle clearly called us on it,” and how it was a travesty that the black artist community in Portland was shunned by the Biennial, because they were responsible for the best work in the city. (She pointed us towards Brown Hall PDX and Home School PDX as two groups deserving of our attention.)

Cherry and Lucic—named for ice hockey commentator Don Cherry and feared NHL fighter Milan Lucic, and a play on LA gallery Cherry & Martin—is actually a self-described “semi-dilapidated garage” outside an artist house that holds one-night-only shows (because the roof leaks). Their contribution to the Biennial is a faithful recreation of Merlin Carpenter’s Poor Leatherette, an assembling of a motorcycle, DJ equipment, a baby carriage, and a refrigerator in a gallery.

They reached out to Carpenter about the re-creation, but ultimately decided to go ahead with it, simultaneously releasing a novella as part of the Biennial. Ford went onto say that, though her colleagues disagreed to an extent, she felt Carpenter’s original piece was “a privileged display,” but that curating a Merlin Carpenter show would look “dope on [Cherry and Lucic’s] CV, because this work is now ours, and we deserve to profit from this.”

Julia Oldham. Courtesy of Maxwell Williams.

Grabner’s show sparkles with moments like this, but they don’t quite overwhelm it. While the main salon at Disjecta diplomatically includes a work from every artist Grabner held a studio visit with, Portland-based social practice “grandfather” Harrell Fletcher’s influence doesn’t loom as large as one might think. Instead, as Grabner says, environmentalism and landscape-based work whispers in the background.

“Those would be the two things that I anticipated [would be unavoidable regional ideas] that didn’t play out—maybe not in the abundance that I thought would be the lay of the land,” she told me. “There’s something about Portland that’s oddly a crucible in a very defined contour of community, and it’s a little insular, but within that insularity, really great things are developing. That may be five craft breweries popping up, or some really interesting art initiatives. It’s leftist Libertarianism. And their greatest threat is people [moving to Portland] from the outside—and that burdens housing prices, traffic, and infrastructure. All the utopic bits that create the desire to be here.”

The most difficult thing, however, may not be conceptual concerns, but physical limitations. It will be very, very difficult to see the entirety of the Portland Biennial this year. I loathe writing authoritatively about a show I’ve only seen parts of, but to see the whole thing would take at least a few days of crisscrossing the state to Eugene, Pendleton, Clatskanie, Bend, Ashland, and more. What I saw of Oregon, on the trip to Astoria, was that it’s an overwhelmingly lush state, and that the biennial-as-a-road-trip can work in such a place worthy of long car rides already.

Michelle Grabner (left). Courtesy of Maxwell Williams.

Back in Portland, on the day of the opening, Grabner and Jens Hoffmann, deputy director of the Jewish Museum in New York, held court in an event space at the Ace Hotel called The Cleaners before a packed house. They talked about the direction of biennials, whether or not they were “broken,” the incomparable differences between curating this and the Whitney Biennial as Grabner did in 2014, and what regionalism means during such a rapidly globalizing moment.

It got me thinking about the purpose of a biennial, and what some of the criticisms that were leveled on the DIS-curated Berlin Biennial. Was it dealing with the issues of our time? Did it need to be? Were there underlying concerns that it’s overall value might have profited from?

Maybe that’s a problem with this sort of isolationism. What seems important to a writer flying to Oregon from LA might not hold the same weight in the Pacific Northwest, but don’t we all see the same things on the Internet?

Emily Bernstein and Julia Calabrese, still from The Cosmic Serpent (2015). Image courtesy the artists.

Still, Hoffmann brought up the fact that the first Venice Biennial dates back to 1895, ushering in a systematic new way of checking in on art in two-year increments. I’d like to point out that in 1895, it was still illegal for black Americans to move to Oregon, the only state in the country that had this type of law on the books, and it stayed that way until 1926. Interestingly, only 23 years later, the Portland Art Museum held the first Oregon Biennial. That was abandoned in 2006, and Disjecta, a non-profit down the road from the Paul Bunyan statue—and kitty corner to a strip club called Dancin’ Bare—on the northeast side of Portland, revived the biennial in 2010.

This is its fourth edition, and second with an outsider as curator, giving an interloping perspective on art in Oregon. As an interloping journalist at the Biennal, I see an outsider wrestling with being an outsider and the anxiety of the locals reflecting it. It’s this refraction that makes Disjecta’s latest venture worth exploring, and it gives the Biennial a heft that should be noted by audiences beyond the state’s residents.