Art Fairs

How the Upstart Ramallah Art Fair Was Organized Amid a Pandemic and the Trials of Daily Life in Palestine

The show involves 26 artists and has been staged at Zawyeh Gallery.

The show involves 26 artists and has been staged at Zawyeh Gallery.

Rebecca Anne Proctor

An in-person event is a rare thing these days. Even rarer is a new fair in Palestine. Yet the Ramallah Art Fair, which opened in December and continues until March 4, has proven that it’s possible—especially if you’re willing to break the traditional art fair model.

Instead of a fair composed of galleries, the event comprises just artists and is staged in a single location: Zawyeh Gallery, Palestine’s only international gallery dedicated to modern and contemporary Palestinian art. (It also has a location in Dubai.)

The gallery’s owner, Ziad Anani, invited 26 artists to take part, giving each one space to exhibit five to seven small pieces that he worked to place with international collectors.

“We were looking to exhibit smaller works in an affordable price range of a maximum of $5,000, and to sell them also to collectors outside of Palestine—in the U.A.E., the U.S., Lebanon, the U.K., and throughout Europe,” Anani tells Artnet News. “The collectors were immediately interested, with many reserving pieces before the fair started.”

For some of the artists in the show, such as Sliman Mansour and Nabil Anani, the price points were lower than what they had previously commanded.

“But they accepted because they wanted to be part of the fair and part of the group of Palestinian artists to encourage collectors and local Palestinian artists to buy art,” Anani says. Since opening, Zawyeh has sold nearly 30 percent of the exhibition. “We’ve been overwhelmed with sales—both from online and in-person.”

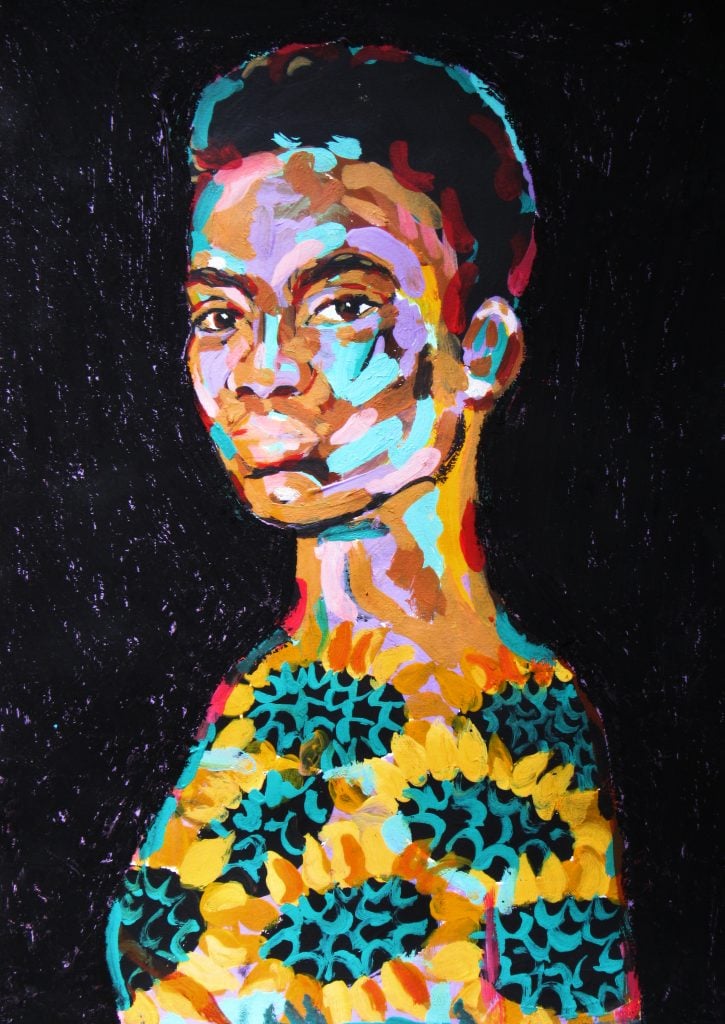

Silman Mansour, Jerusalem Rooftops (2007). Courtesy of the artist.

Staging the Ramallah Art Fair was no small feat.

The artists—including Asma Ghanem, Bashar Alhroub, Khaled Hourani, Rana Samara, and Mohammed Khalil—hail from across Palestine, Gaza, the West Bank, the 1948 territories, and Jerusalem. Transporting their works to one location is a challenge, even in normal times.

“Even without Covid, we have restrictions on movement in Palestine from one city to another due to the occupation,” Anani says. “There are always checkpoints and it’s always very hard for people to travel, even if the distance is small.”

But in a pandemic, the logistical issues intensified. Ramallah is currently under a daily 7 p.m. curfew, and all businesses must be closed on weekends. The Palestinian territories have suffered serious blows from the coronavirus pandemic, compounding their dire economic states and exposing Palestine’s fragile health system, all of which reflects back on artists.

“We realized that the artists were isolated in their studios and doing works that many times reflected the current situation,” Anani says, adding that the fair was “our way to support young and established Palestinian artists, but also a way for us to survive as a gallery during these challenging times.”

“We have no collectors in Ramallah, and, for the time being, we also don’t have any art galleries, apart from ours,” Anani added.

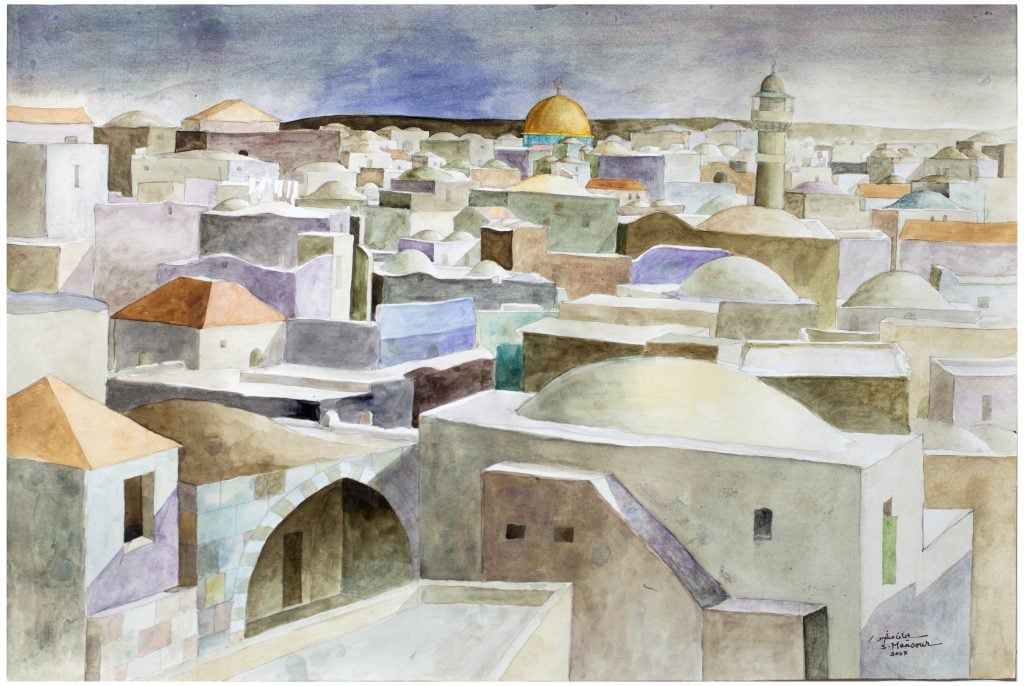

Khaled Hourani, Unnatural Landscape #11 (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

Artworks on display reflect the politics of place—a crucial theme for creatives from the region—and each object is tinged with an element of nostalgia for the Palestine that once was, and perhaps could be.

Some artists, like Khaled Hourani, depict the Palestinian landscape under occupation through picturesque landscape disrupted by the Israeli occupation wall. A work by Fouad Agbaria, meanwhile, depicts an olive tree as black instead of the conventional elegant green, reflecting the brutality of occupation. Olives have historically formed an important part of the Palestinian economy: 48 percent of agricultural land, primarily in the West Bank, is planted with olive trees. But to build the Separation Wall and infrastructure for Israeli-only settlements, over 800,000 olive trees have been destroyed.

In a different light, abstract paintings by Yazan Abusalameh portray the harsh reality of everyday life under occupation, with the heavy presence of military structures. Still, he always paints tiny colored windows symbolizing hope amidst otherwise bleak scenes.

“It is very emotional for me to see my art next to works by my professors, such as Khaled Hourani, Hosni Radwan, Nabil Anani, Mohammad Khalil, Bashar Alhroub, and other artists that I admire,” Asma Ghanem says. “The fair gave the audience something new. It reflected the culture and art that makes up Palestinian society. The feeling of community was strong.”

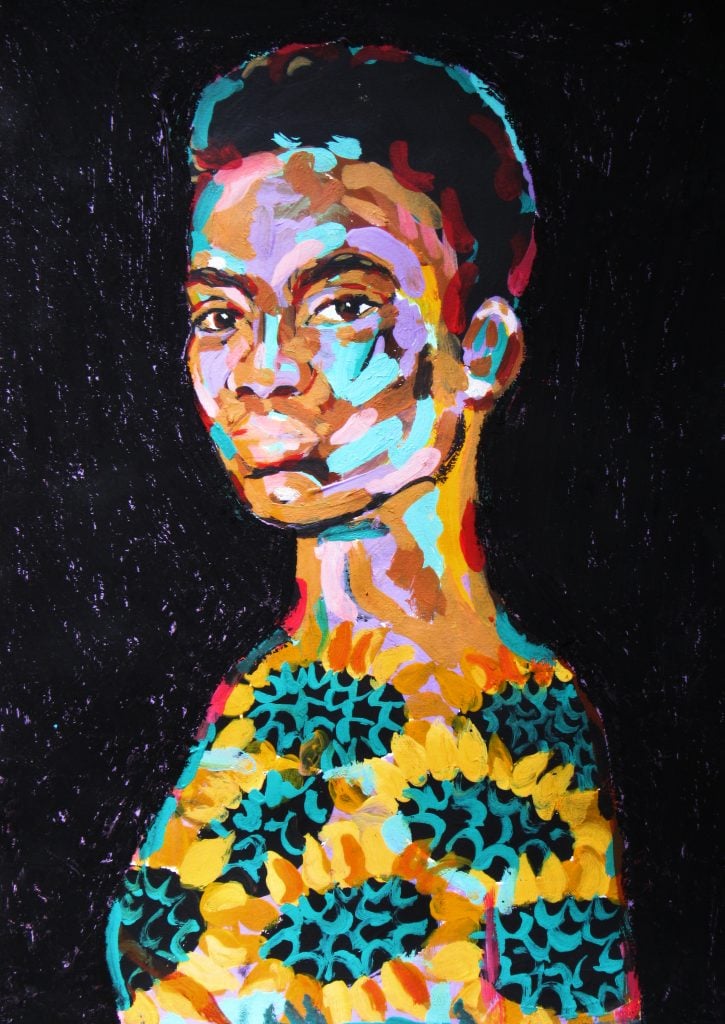

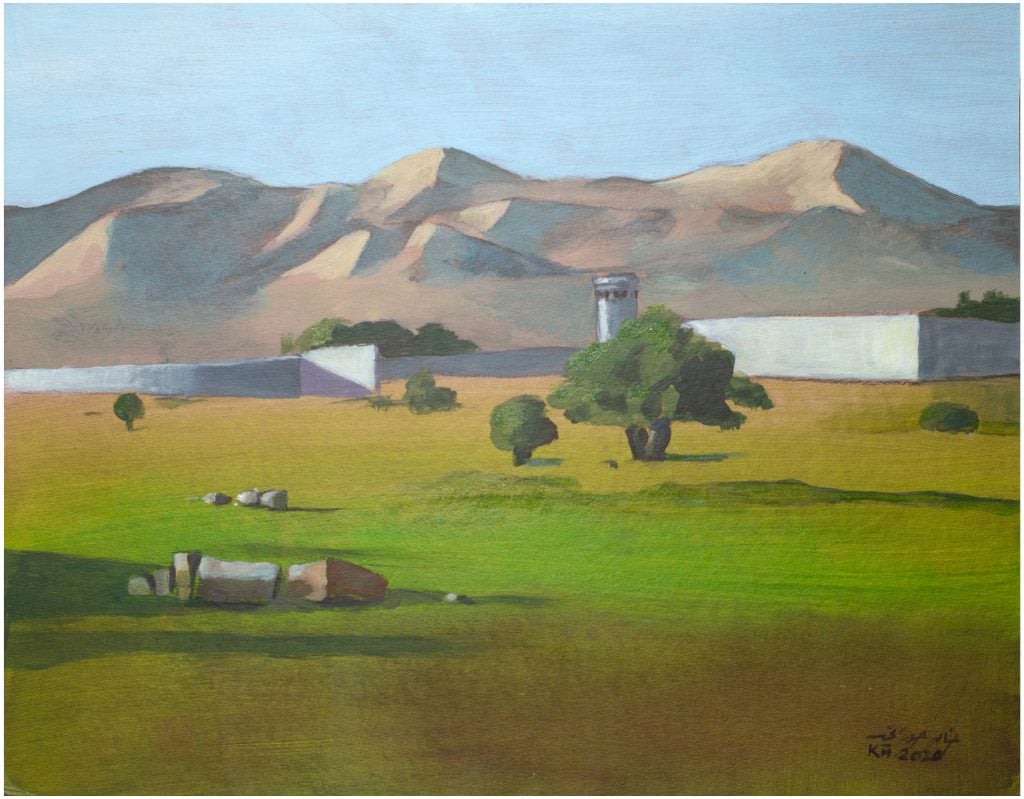

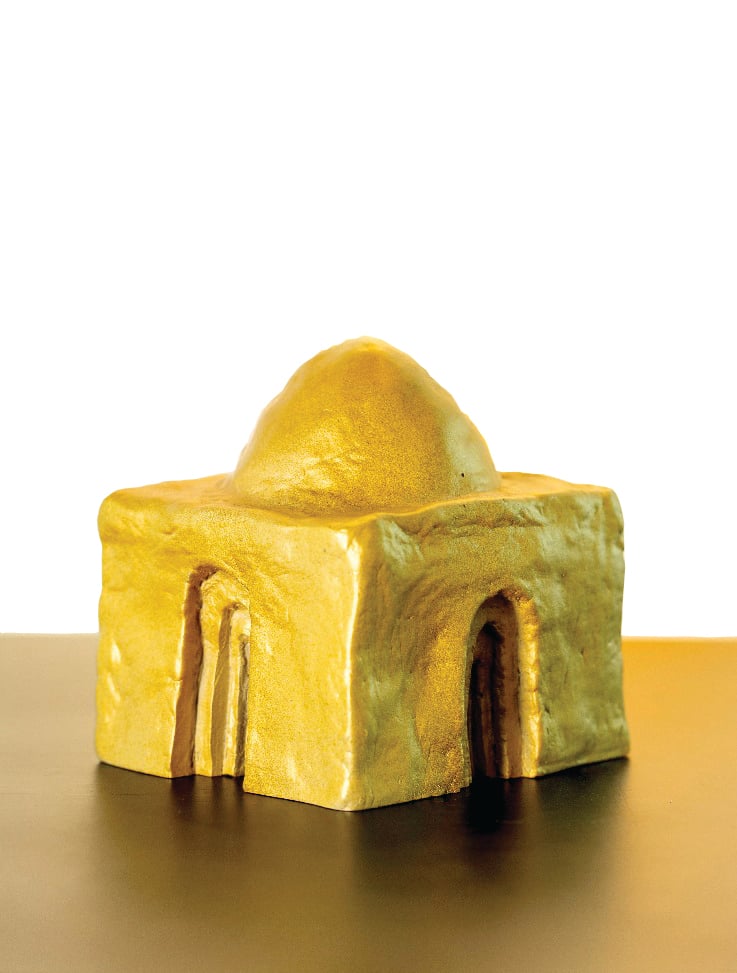

Bashar Hroub, Almakam. Courtesy of the artist.

Apart from being a commercially successful enterprise, the fair has also had a positive effect on Palestine’s growing art community.

“Cultural life practically stopped [amid the pandemic] and the ties that unite people were lost,” Mansour says. “The pandemic nearly stopped the art market, so the Ramallah Art Fair helped many artists, especially young ones. It brought people together again and has left a mark on the cultural life of Ramallah.”

“After almost one year of not having a chance to exhibit anywhere, the fair gave Palestinians the chance to attend a real exhibition again,” Ghanem says. “People who don’t usually buy art felt they could because of the affordable prices. This was a push to generate more local collectors and benefit Palestinian artists during these hard times.”