Auctions

Sotheby’s Faces a ‘More Sober’ Market With a Modern Art Marathon—and Comes Away With $427 Million

The evening began with the cream of the Mo Ostin collection before moving to (mostly) modern works.

The evening began with the cream of the Mo Ostin collection before moving to (mostly) modern works.

Katya Kazakina

A shimmering landscape by Gustav Klimt fetched $53.2 million at Sotheby’s on May 16, leading a three-hour evening auction marathon that kept on morphing with last-minute withdrawals, additional irrevocable bids, and dramatically reduced reserves.

In the end, the maneuvering paid off: Sotheby’s total for two back-to-back sales reached $427 million, smack in the middle of the presale target. (The final prices include fees, estimates don’t. It should be noted that Sotheby’s charges 26 percent on top of the hammer price of up to $1 million.)

While Sotheby’s touted the overall results as its third-highest tally for a single evening, this outcome was not always evident in the salesroom. At times painfully drawn out, the proceedings were conducted by Sotheby’s auctioneer Oliver Barker, who fought for every bid, no matter how small or how long it took to get it.

“He wasn’t able to boss the room like he normally does,” said art dealer Ray Waterhouse. “He allowed people to take time. It was slow.”

The salesroom often seemed stubbornly silent, with lot after lot selling on a single bid to Sotheby’s staffers, presumably representing the third-party backers.

Cecily Brown, Free Games for May (2015). Estimated at $3 million to $5 million, it sold for $6.7 million. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

“People are a little more sober,” said Philip Hoffman, founder and CEO of the Fine Art Group. “There’s still plenty of money around, but they won’t go crazy.”

The evening began with a small dedicated sale of 15 lots from the collection of Mo Ostin, a powerful music executive who died last year. The longtime chief executive of Warner Bros., Ostin was responsible for bringing “a dream-world music hall of fame” list of names to his company’s labels, read the New York Times obituary. “It includes pivotal singers of the 1950s like Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby and Sammy Davis Jr.; innovators of the 1960s and ’70s like Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell and the Grateful Dead; and game-changers of the ’80s and ’90s like Madonna, R.E.M., and Green Day.”

Along the way, Ostin assembled an enviable art trove, which is offered at Sotheby’s in evening and day sales.

“Mo’s love of art was second only to his love of music,” his friend the actor (and fellow art aficionado) Steve Martin once said.

Gustav Klimt, Insel im Attersee (ca. 1901–2). With an unpublished estimate, it sold for $53.2 million. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Tonight, the first batch generated $123.7 million, in the middle of the presale estimate range of $103.3 million to $155.3 million; only one lot, a Willem de Kooning work on paper, failed to sell. The group’s star was an iconic painting by René Magritte, L’Empire des lumières, which depicts a dark street with an illuminated house set against bright blue sky. The 1951 painting was estimated at $35 million to $55 million. It drew four bidders and took more than 10 minutes to sell, starting with the opening bid of $24 million and inching up in increments of $500,000.

The final price of $42.3 million stopped well short of the $79.4 million auction record for the Belgian Surrealist painter, achieved just a year ago for a later and larger version of the L’Empire des lumières. (There are 17 paintings in the series; Ostin purchased his, numbered “III,” in 1979, according to Sotheby’s.)

Another Magritte, Le Domaine d’Arnheim (1949), fetched $18.9 million against an estimate of $15 million to $25 million. Taking its title from a short story by Edgar Allan Poe, the canvas depicts a mountain range with a peak shaped like an eagle, seen through a shattered window.

A highlight was Free Games for May, a painting by Cecily Brown, who is currently enjoying a mid-career retrospective at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The first lot of the evening, it drew a flurry of bids, which propelled it past the high estimate of $5 million to the final price of $6.71 million, just shy of Brown’s $6.77 million auction record. The night before, Christie’s sold a larger Brown canvas for $6.7 million.

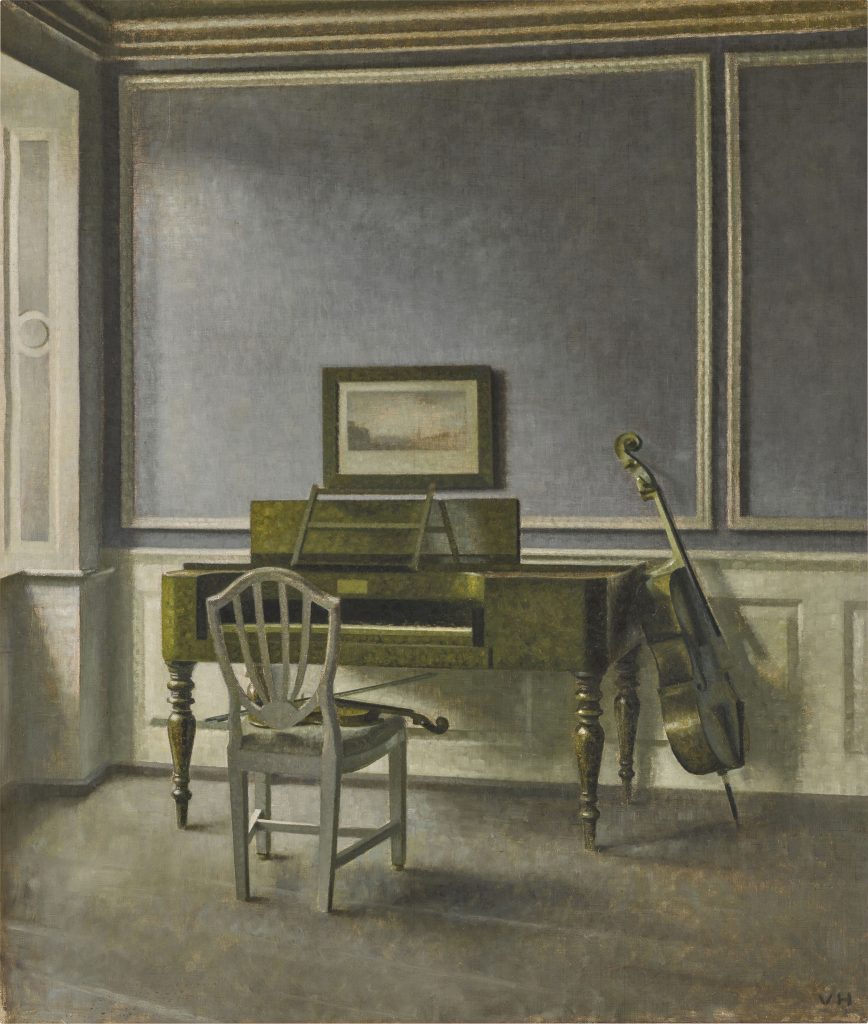

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interior. The Music Room, Strandgade 30 (1907). Estimated at $3 million to $5 million, it sold for $9.1 million. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Not every performance was as starry as Ostin’s musical roster. Works by Pablo Picasso, Joan Mitchell, and Arshile Gorky hammered below their low estimates. Cy Twombly’s 1962 Untitled painting was the most stark example, with Barker releasing it on an offer of $10 million, compared with the $14 million low estimate.

The modern evening auction, which followed the Ostin collection, included 48 lots. The total reached $303.1 million, compared with the presale target of $272.1 million to $378.7 million (adjusted midway through the sale, as additional lots were scraped from the lineup, presumably to avoid going unsold publicly). In all, 83 percent of the lots sold, according to Sotheby’s.

One of the bright spots was a somber room from 1907 by Vilhelm Hammershøi, whose prices have surged in recent years. Estimated at $3 million to $5 million, Interior. The Music Room, Strandgade 30, opened at $1 million and eventually fetched $9.1 million, a new auction record for the Danish painter. It was acquired by an American museum, according to Sotheby’s.

Another record-setter was Isamu Noguchi’s monumental stone trio, The Family (1956–57), which sold for $12.3 million, surpassing the high estimate of $8 million and notching a new high for the Japanese American artist. It included a 16-foot ‘father,’ 12-foot ‘mother’ and 6-foot ‘child’ statue, and was commissioned by the famed modernist architect Gordon Bunshaft in 1956.

Isamu Noguchi, The Family (1956–57). Estimated at $6 million to $8 million, it sold for an artist-record $12.3 million. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Heading into the sale, Sotheby’s had guaranteed 14 lots and parceled off 10 of them to third-party investors (more irrevocable bids were added later). Key among those lots was the Klimt, which would end up going to a private Japanese collection following a seven-minute battle between Brooke Lampley, worldwide head of sales for global fine art, and the chair of Sotheby’s in Japan, Yasuaki Ishizaka.

The six withdrawn lots included works by Henri Matisse, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Paul Gauguin. Eight more failed to sell, including two of the four works consigned by the heirs of the legendary French dealer Аmbroise Vollard after the resolution of a restitution case earlier this year.

The most valuable of the Vollard group, a Gauguin still life, Nature morte avec pivoines de chine et mandoline (1885), had resided in Paris’s Musee d’Orsay from 1986 until now. Estimated at $10 million to $15 million, it drew a single bidder, Wendi Lin, Sotheby’s chairman of Asia, selling for $10.4 million. Asian collectors were active throughout the sale, according to the auction house, buying a third of lots by value.

Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of a Man as Mars (ca. 1620). With an estimate of $20 million to $30 million, it sold for $26.2 million. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Surprisingly—and indicative of brazen category creep practiced by the auction houses—the modern sale included a 400-year-old painting, Portrait of a Man as Mars (ca. 1620), by Peter Paul Rubens. It was one of four lots guaranteed by Sotheby’s without being backed by an irrevocable bid. Estimated at $20 million to $30 million, it fetched $26.2 million, the fourth-highest price for the Dutch Old master.

A more typical entrant, Edward Hopper’s landscape, Cobb’s Barns, South Truro (1930–33), was consigned by the Whitney Museum of American Art to support future acquisitions. Sadly, it drew just one bidder, despite having graced the walls of the White House’s Oval Office under President Barack Obama. It sold for $7.2 million, failing to hit the low estimate of $8 million.

In sharp contrast to last week, Georgia O’Keeffe didn’t have a good night either; both of her two paintings failed to sell. One of them, Lake George Barn (1929), was guaranteed by Sotheby’s (and estimated at $4 million to $6 million).

“It may look like it wasn’t such a great sale, but to me the estimates were just too high,” said Andy Terner, a private art dealer. “It’s really competitive, particularly this year. I think there’s some reluctance to sell into an uncertain market. The auction houses are almost forced to be aggressive with the estimates. But the market speaks for itself the night of the auction.”