In recent years, Sotheby’s has sold objects as disparate as the plastic crown worn by the Notorious BIG and spooky photographs of UFOs. Now, it is consolidating these eclectic offerings under the banner of a new department: science and pop culture.

The division’s head, Cassandra Hatton, might at first seem like an unlikely candidate for the job: she previously worked in the books and manuscript department, the oldest specialty at Sotheby’s. (Books were the first objects Sotheby’s ever sold back in 1744.)

But Hatton, a former private dealer who made the leap to auctions about eight years ago, has the kind of omnivorous taste that makes her well suited to such a position.

Andy Warhol’s Bust of Leonardo da Vinci pictured here on the wall behind the artist and Jean-Michel Basquiat is estimated at $200,000 to $300,000. Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

Hatton’s background is rooted in the history of science (particularly 17th-century science). Having completed her graduate thesis on Galileo, she expanded her expertise to 20th-century physics, computing, and space exploration while building a business as a private books and manuscript dealer.

After she joined Bonhams’ books and manuscript division in 2013, she began to encounter unrelated objects like space suits directed her way. “It was a really quick education,” Hatton told Artnet News.

How does one face such a curveball? “I approached it in the same way that I would a Galileo manuscript,” she said. “When I described a space suit or an object that flew to the moon, I did it in a serious way. I treated the objects with seriousness and so people took the objects seriously.”

Richard Feynman’s bongo drums. Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

It wasn’t long before Sotheby’s, noting the success of her catholic approach, poached her. She began introducing space exploration, technology, and hip-hop sales alongside traditional manuscript offerings. Of hip-hop sales, she said, “I saw that there was tremendous potential for it, a huge amount of history, and an untapped market.”

Hatton’s new umbrella department is currently holding its first sale (through April 28), offering objects ranging from a complete skull of a triceratops (estimate: $400,000–600,000), to a bust of Leonardo da Vinci formerly owned by Andy Warhol (estimate: $200,000–300,000), and a 19th-century compilation of glass eyes ($80,000–100,000).

“Many of the items that are selling for quite a lot of money you might look at and think they’re nothing,” Hatton said. “It’s when you hear the story behind them that you get really excited about it. I think that’s the common theme among everything I sell: the story is exciting.”

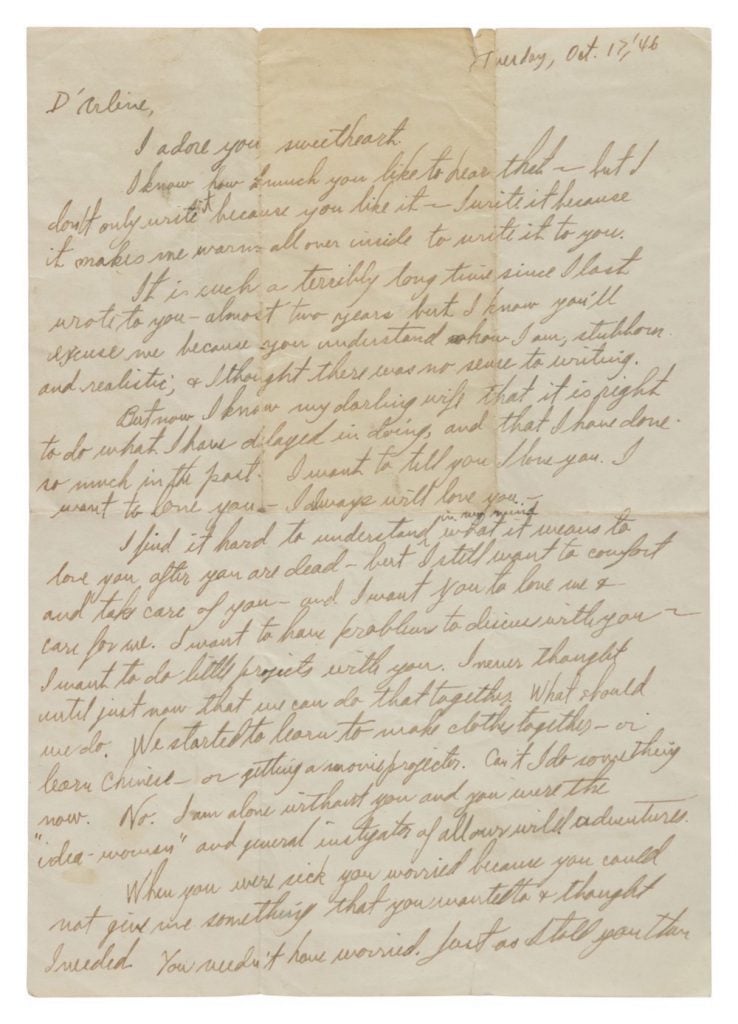

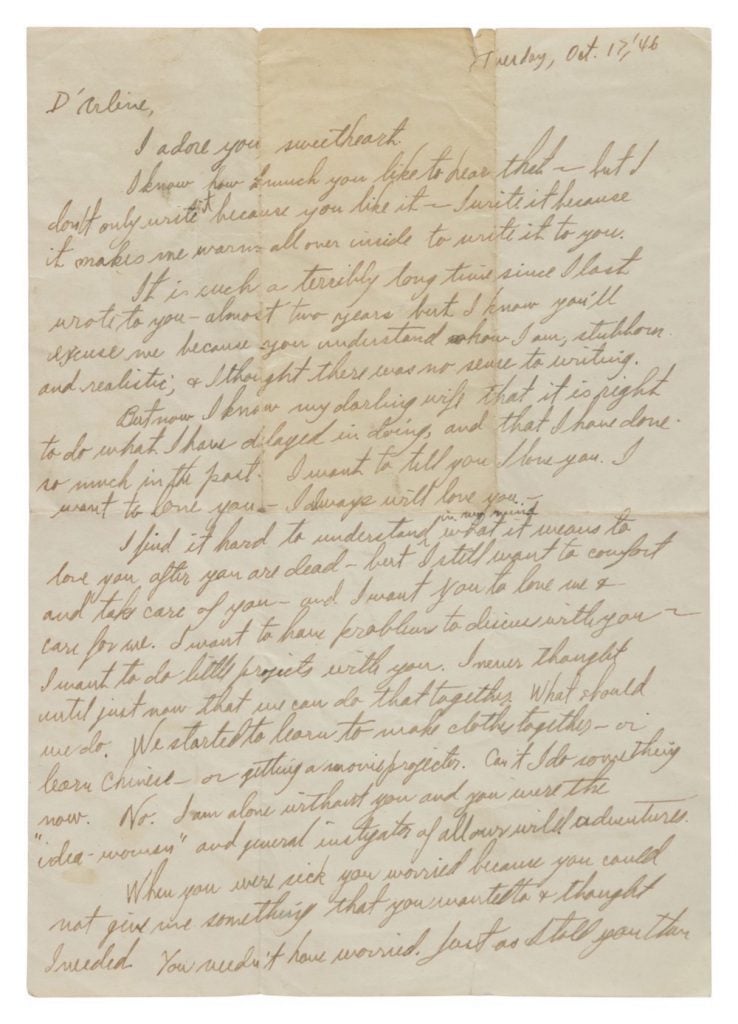

The famous love letter written by Richard Feynman to his wife Arline, 16 months after her death from Tuberculosis at the age of 25. Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

The audience, she says, is as eclectic as the objects themselves. Bidders have ranged in age from 24 to 90-plus. Silicon Valley types, unsurprisingly, tend to be particularly interested in objects related to the history of technology. (Plus, we know at least one Hollywood actor, Leonardo DiCaprio, is a fan of dinosaur-bone collecting.)

“People ask me that question a lot: How do you find these buyers?” Hatton said. “They are peers. They have a shared love and understanding of most of the items that I sell.”

While objects tied to astronauts largely appeal to American buyers (“It tends to be driven by that cult of the American hero”), others have universal interest: “Math is the same everywhere, physics the same everywhere,” Hatton said. “The moon is the same for everyone.”

What won’t she sell? She is not particularly interested in objects that have multiple editions or copies, like a first edition of Darwin’s Origin of Species. “If there was a copy that Darwin or some other prominent person had written extensive notes in, that would be different,” she added.

But it’s not only the story behind an object that increases its value, Hatton explained—it’s also the brevity with which that story can be expressed. That can be the difference between a Nobel Prize that sells for $250,000 and one that sells for $5 million.

“The fewer words you need to explain why the person was awarded the prize, it will sell for more,” she said. “The two highest prices ever achieved for Nobel Prizes were Crick and Watson for discovering the structure of DNA. All you have to say is DNA, you don’t even need a word.”

Sotheby’s books and manuscript department is remaining intact. Hatton is currently putting together a team of experts to help grow the new department and is aiming to have four sales annually.