The Art Detective

Shoptalk: Dealer Stefania Bortolami on How Interdependence Has Shaped the Contemporary Art Scene

"It’s a tough moment, in which we have to buckle up and take some strategic decisions."

"It’s a tough moment, in which we have to buckle up and take some strategic decisions."

Katya Kazakina

Shoptalk is an interview series about the experiences of women art dealers and industry insiders of various generations, as told to Artnet’s Art Detective columnist Katya Kazakina. Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access—subscribe now.

When I met Stefania Bortolami in 2006, she had recently opened a gallery on West 25th Street in Chelsea with partner Amalia Dayan. Having worked at Gagosian, the two women brought glamour and savvy to the rapidly expanding emerging art scene. They showed fashionable young artists like Aaron Young as well as French conceptualist Daniel Buren, known for his site-specific installations featuring stripes. Their openings were frequented by art world celebrities like Sotheby’s star auctioneer Tobias Meyer and his husband Mark Fletcher, who was Bortolami’s former colleague at London’s Anthony D’Offay gallery in the 1990s.

After the partners split in 2007, Bortolami went solo, taking over the space and later moving to West 20th Street, where she was neighbors with Anton Kern and Jack Shainman. In 2017, Bortolami became the second gallery to open on Walker Street in Tribeca, next to Alexander and Bonin, with a memorable intervention by Buren.

Today, Bortolami, 58, programs three spaces on the block, including 55 Walker (previously the home of Artists Space), which she shares with Andrew Kreps and Kaufmann Repetto galleries. As the gallery matured, it shifted towards female artists, who now account for 19 of the 29 on the roster.

Barbara Kasten’s project in townhouse in Philadelphia became the impetus for Bortolami’s “Artist/City” initiative. Courtesy: Bortolami Gallery

While Bortolami self-describes as a “proud mid-size gallery” with no ambition to go mega, she’s been wielding soft power to expand her sphere of influence. She’s known for collaborating with fellow dealers and hosting fashionable dinners and behind-the-scenes social events like the Lesbian and Bisexual Backgammon League.

In 2015, instead of opening branches outside of New York, she launched “Artist/City” to counterbalance the art trade’s relentless churn. These long-term exhibitions across the U.S. have lasted for as long as a year, often in defunct spaces such as a former Taco Bell in St. Louis, Missouri; a Marcel Breuer-designed relic in New Haven, Connecticut; and old Greyhound station in Las Vegas, Nevada. Participating artists have not always been on the gallery’s roster. In 2021, Cecily Brown, whom Bortolami met at Gagosian back in the day and who is godmother of her daughter Maya Fuchs Bortolami, did a giant mural on a school building in Buffalo, New York.

This summer, Bortolami is in the news as part of The Campus, a six-gallery collaboration in a former public school in Claverack, New York. Despite the bleak art market data, Bortolami resists what she sees as the “doom and gloom” view. She spoke candidly about the realities of the trade while maintaining an optimistic outlook. Below is an edited version of our conversation.

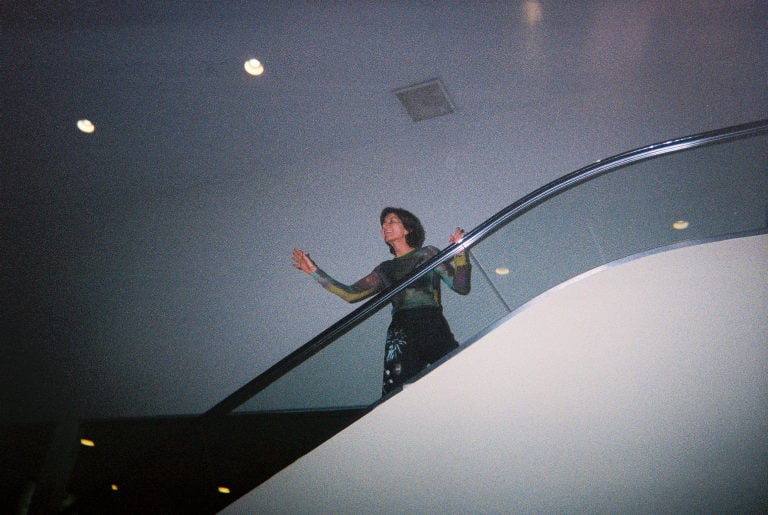

Stefania Bortolami, toasting artists from the top of a moving escalator in Las Vegas. Photo: Ellie Rines

Collaboration seems to be the word of the summer, but in your case, I feel like it’s what you’ve done for many, many years.

Collaboration has become a buzzword, but it’s nothing new. In olden times, I’m talking about before the existence of mega-galleries, an artist would have a gallery in New York, a gallery in Europe, maybe a gallery in Los Angeles, and the two or three galleries would collaborate to promote the artist’s career.

With Andrew Kreps and 55 Walker it was not a conscious decision. There was this space because Artist Space had moved, and we decided to take it ourselves. And then, his wife also needed a space. (He’s married to Chiara Repetto of the gallery Kaufman Repetto in Milan, and when they got married, she came to live in New York. She was doing little shows in his gallery in Chelsea.) We looked at the numbers and divided by three. It was not very expensive.

With The Campus, it was a little bit the same thing. Andrew just found this school, and then rather than buying it himself, he said it would be more fun to do it with other people. So, then he called, basically, his buddies, and we all went, “Yes!” It was not, “Oh, let’s now collaborate.”

We all have independent galleries, but it’s also very enriching to have the interdependence. I don’t know what’s the difference between collaboration and interdependence, but collaboration is the contrary of competition and interdependence is versus independence.

Collaboration presumes you are sharing the risk.

Sharing the risks and rewards.

You guys bought the school in 2021 when the interest rates were very low still.

We got very lucky. Frankly, there’s not that much risk. So, we have a lot of plans.

French artist Daniel Buren painted his signature stripes on the facade of Bortolami Gallery for its opening in Tribeca in 2017. Courtesy: Bortolami Gallery

What kind of plans?

Maybe build up storage for other people. We’re buying a truck so they can do a shuttle twice a week from New York.

We hired someone who is an incredible woodworker and had a shop in New York City that did crates and pedestals for some very big galleries like Zwirner and whatnot. We bought his business.

What I’m saying is that there’s several things that we can do apart from putting up exhibitions and doing events. We can also grow it as a business.

It’s a good time to generate additional cash, considering the downturn in the art market. What’s it like for you?

It’s a tough moment, in which we have to buckle up and take some strategic decisions. Trust me, all the galleries, we’re thinking: How do we go through this? Maybe to share booths at art fairs. Sit down with artists and maybe instead of having 14 paintings in a show, let’s just have seven great paintings. Let’s keep doing what we’re doing but be more focused. There’s a lot of supply of art for sure. And yes, maybe contemporary art is a little bit too expensive.

Many collectors complain about how high prices have gotten. Why is art so expensive?

This ‘too expensive’ argument, I don’t get it.

Let’s take three artists who are the same age and they each did two museum shows recently. Their prices can literally range from $50,000 up to $1.5 million. They have very similar CV, except the difference: Which gallery they show at. And yet they have the same chance to still be relevant in 50 years. Which one is too expensive?

Tom Burr / New Haven, Phase 1, 2017, installation view, Bortolami, New Haven

You can send a child to a private school for a year for $50,000 in New York!

Usually, our collectors are people who do not have a problem paying for private schools. In order to operate as a gallery, you need to make a little bit of money. When a museum does a monograph of an artist, where do you think they get the money? It costs $50,000, $60,000, $70,000 to do a monograph. We pay for a lot of it. The costs are impossible!

It’s a catch-22 for galleries and for artists, who get stuck with those high prices and when fashion changes, suddenly no one wants their work. What are they supposed to do?

They teach. I love to represent artists that teach because they are independent in that sense, they can continue to experiment. If you become, as an artist, completely dependent on people buying your work, it can be problematic.

Stefania Bortolami, left, at the opening of The Campus in Claverack, New York. Courtesy: Bortolami Gallery

What about lowering prices? In every other industry, in every other sector—take fashion, automobiles, real estate—cutting prices is a way to entice appetite and demand.

Because you need a car. You don’t need art. You buy it if you like it, if you want it. If you don’t want it, whether it costs $20 or $200, it is the same thing.

The thing is not to raise the prices too quickly. There must be a reason to increase the prices. The artist got a traveling museum show? OK, let’s put the prices up 20 percent. Just because it’s one year later or two years later, does not mean that the prices have to go up.

Back in 2013, you told amNewYork newspaper that art is a good investment.

That was a very different time, when art started to increase in values exponentially. Right now, we might have arrived at a plateau.

Do you still think art is a good investment?

It’s a very good cultural investment. It’s also an investment in humanity. We need to make art and we need to support the making of art. That’s what we do.

Sheri Pasquarella, Stefania Bortolami (center left), Ellie Rines, and Lily Snyder play backgammon. Photo: Annie Armstrong

I noticed that women now make up two-thirds of your program. Is this by design?

It was not a conscious decision. It’s simply because you go to biennials, and you see more women artists. When I started in the art world, there were very few women artists in museums and biennials. Now there’re probably more women than men.

So, your program simply reflects a broader change?

Yeah. You have to find an artist that speaks to you and when you find one, you try to offer them something.

Do you have any advice for younger art dealers?

Accept the fact that you are going to make mistakes in terms of artists that you pick, or artists that you did not pick. Otherwise, you go crazy.

Stefania Bortolami with her daughter Maya Fuchs Bortolami, tapped to oversee art programming and sales at Casa Tua New York. Courtesy: Bortolami Gallery.

You’ve worked with many “hot” artists over the years. Any advice on how to protect artists from flippers?

There’s nothing you can do. Big, important collectors started flipping too. Most contemporary artists are not flippable. Some of it, the moment it leaves the gallery it is worth half, and it will always be worth half or a third or something. Again, we are talking about monetary value.

What new trends are you seeing out there?

It’s a transitional moment. I’m hopeful that maybe the painting-only fever might break and that we’ll become diversified again with painting, sculpture, installation, and photography.

What about the next generation of buyers? What are they like?

There’s a lot of young collectors and some of them even buy for the right reasons, not just to invest. My daughter is 23. She’s starting in the art world and she has a lot of friends her age that buy art.

An installation by Tom Burr at Bortolami Gallery, 39 Walker Street. Courtesy of Bortolami Gallery

You’ve been very critical of the mega galleries in the past.

Frankly, we now need the mega galleries. Please, mega galleries, do not disappear.

You are so funny.

We need them because they attract a lot of people to the art world. They are sexy and glamorous. And actually, in the last couple of years or so, mega galleries also decided that it’s kind of nice to collaborate. I think that mega galleries got a little fed up with their bad rep and having to do everything themselves.

Where do you see your gallery in 10 years?

I am a proud mid-size gallery. I don’t think it’s going to be very different. Hopefully my artists will get bigger museum shows. I want MoMA.

Look, if one day I find a fantastic place in Europe, where I could add something else, then maybe I will do it. I’m certainly not opening in Los Angeles or Hong Kong. I have zero interest in this.

I respect a lot what my friend Thomas Dane did. He opened a space in Naples, in Italy. So that’s a very nice move because everyone is interested in Naples as a city. He’s in London, so at least it’s close by. I would have to do it in Naples, Florida!