Galleries

Once-Infamous Painter Taner Ceylan Explores the Portraitist’s Role in New Show

It all began with an intimate viewing of Ingres's Princesse de Broglie.

It all began with an intimate viewing of Ingres's Princesse de Broglie.

Laura van Straaten

On Friday afternoon, on the sunny back patio of the Hotel Americano in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, the Istanbul-based painter Taner Ceylan mused over the stakes of his second solo show at Paul Kasmin Gallery, which opened the night before.

“First, I ask, ‘Do I have the courage to paint or not?’ And this is the very hard part,” he said. “But then it’s, ‘Do I have the courage to show this work?’ And then there is the reaction of the public—those are hard too.”

The previous night, a troupe of his friends and colleagues had lingered long and late to celebrate Ceylan at a dinner Paul Kasmin hosted in the artist’s honor. And in the noon glare, as Ceylan ordered espresso with a chaser of black tea, he was beaming.

Ceylan gained fame for painting homoerotically charged scenes with hunky men (often nude and always well-hung) and for a series that revisited Orientalist figurative painting to expose and deconstruct hidden tales in Turkish history, often with a high level of sexual content.

With the fame came infamy in his home country. He was forced to resign his position at Istanbul’s Yeditepe University and then, there were the threats. “I lived with [a] body guard and two policemen outside my door…for three or four months,” he said and recalled one of the threats: “‘How can you paint an Ottoman woman in front of a vagina? We will kill you!’” He added, “I’m not the only one of course, because art is a very strong language in Turkey.”

Installation view of Taner Ceylan’s “Now we must say goodbye,” at Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Image: Courtesy of Paul Kasmin Gallery.

His new work on view in New York is far more subtle. Two canvases comprise the centerpiece of the show, “We now must say goodbye.” On one, Ceylan has painstakingly recreated Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s portrait Princesse de Broglie (1851-53), but with an image of Ingres’s head replacing that of the Princess’s. Facing that work is a much smaller painting, a copy of Princesse, cropped to show just her head and shoulders.

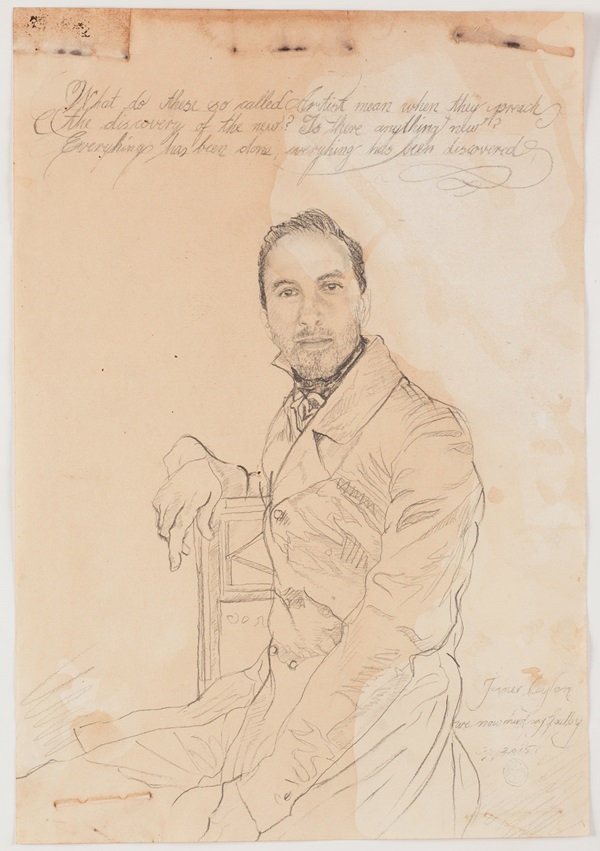

By reuniting the portraitist and sitter in this way, Ceylan has also made a discomfiting gesture of decapitation that disrupts the traditions of the gendered gaze. (In Ingres’s day, painter and sitter would have spent countless hours together as she posed, and the “goodbye” of the exhibition’s title refers to their uncoupling upon the completion of a portrait.) That gesture is replayed throughout the Kasmin show, which includes 10 small works in which Ceylan has placed his own portrait within replicas of Ingres’s drawings.

The genesis of the Kasmin show can be traced to a meaningful moment that Ceylan had with Princesse at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was 10 years ago, during Ceylan’s first solo show in New York, at a time when he spent every minute possible at the Metropolitan. Eventually, Ceylan reached out to one of the museum’s curators, Ian Alteveer, to inquire about ongoing and intimate access to Ingres’s Princess. “I took my Pantones [color samples] and my texts about Ingres,” Ceylan said, “and I sat in the Lehman Collection in front of the painting for hours at a time.”

Taner Ceylan, Princess Broglie (2015).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

“The critics said the painting was so glamorous and shiny that it was about Ingres, not about the princess,” Ceylan said explaining why he was attracted to Princesse. That criticism invoked Oscar Wilde’s oft-cited line, “every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter.… [It] is rather the painter who, on the coloured canvas, reveals himself.”

“Taner is interested in delving deeply into historical paintings and into the cultural and social conditions in which they were painted,” said Kasmin’s senior gallery director Nick Olney, who organized the current exhibition. “He is asking, ‘What are those stories that can be told that are relevant to history and to now?’ and using his imagination to question, explore and reconstruct the past.”

Ceylan identifies with another contemporary artist known for his mastery of the techniques of historical painting: New York painter John Currin. “I love his paintings. They are sexual, as mine are,” Ceylan said, noting that both he and Currin “paint in a traditional way that needs time, passion and silence,” all of which Ceylan feels are scarce and undervalued in today’s world. Tapping his head, he said, “John Currin is always, always here.”

Those concerns about history are relevant also to Ceylan’s commission for the 14th Istanbul Biennal. At the behest of organizer Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Ceylan copied Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo’s Il Quarto Stato, a painting 10 years in the making that was considered a failure when it premiered in 1902. Pellizza was devastated and later committed suicide.

Yet, a couple of decades later, Pellizza’s painting became a symbol and an inspiration for workers’ movements worldwide.

“I find his story very tragic and his passion very beautiful,” says Ceylan who also painted a portrait of Pellizza and installed it such that “Pellizza can see his painting all these years later.” Taken together, Ceylan said, “this work gives [Pellizza] a poetic justice.”

Taner Ceylan, Self Portrait 9 (2015).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

In some ways, Ceylan’s biennial commission also speaks to his stance on Turkey’s quashed protest movements that began in Istanbul’s Taksim Gezi Park in 2013 and have gone underground until their quasi-resurgence in the wake of the bombings in Ankara this past weekend.

“It was a utopia in which there was no religion, no nationalism, no race, no sexuality: there was a oneness that was the materializing of John Lennon’s song ‘Imagine,’” he recalled. “It lived only for one week but it is still there as an energy.” He paused for a minute. Then, his eyes gleaming in the sun, he added, “It is the hope of what we have for the future.”

“We now must say goodbye,” is on view at Paul Kasmin Gallery, 297 10th Ave., through October 31, 2015.

Taner Ceylan’s commission for the Istanbul Biennal is on view at the Istanbul Modern through November 1, 2015.