Galleries

How Has the Art World Changed Since 1983? On the 40th Anniversary of His Gallery, Thaddaeus Ropac Has Some Ideas

The stalwart gallerist on shifting art-world centers, tastes, and the enduring vision for his gallery.

The stalwart gallerist on shifting art-world centers, tastes, and the enduring vision for his gallery.

Hili Perlson

“Today we look back with a bit of shame at the time when the art world was very male dominated,” Thaddaeus Ropac reflected on a drizzly afternoon in late July as guests started pouring in to his Salzburg gallery’s 40th anniversary exhibition.

Spread across two locations in the Austrian city—a villa in the heart of the manicured historical center and a converted industrial hangar on its outskirts—the show’s concept is straightforward: Ropac wanted to present works capturing the spirit of the art world around 1983—the year when he opened his first gallery—and juxtapose them with works created today. “In those four decades, I’ve seen art move from the ivory tower to the center of life,” he said with contagious enthusiasm.

Installation view, “1983 | 2023” at Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg. Photo by Ulrich Ghezzi.

In one of the rooms dedicated to the early 1980s, a work by Georg Baselitz, who famously proclaimed women couldn’t paint, hangs next to a painting by the late Austrian artist Maria Lassnig, whom Ropac has represented since the gallery’s early days. Call it heavy-handed, but this gesture encapsulates a certain authenticity and humbleness that the artists in his stable seem to appreciate. “We speak, we fight, we take positions! When we started to represent the estate of Donald Judd for example, some of our painters weren’t happy. I had to defend it. Judd had a strong position against painting, especially figurative painting.”

The story of how Ropac started out as a gallerist has been told many times, and involves a life-altering encounter with the work of German artist Joseph Beuys in 1979, on a school visit to a Vienna museum. Realizing he didn’t have what it takes to become an artist himself, Ropac still wanted to be involved but wasn’t sure how. So he moved to Düsseldorf and took an unpaid gig at Beuys’s studio.

“I came in at an epic moment for the art world, in 1982. It was Documenta 7, and Beuys, a founding member of Germany’s Green Party, was planting 7,000 oak trees in Kassel. And in Berlin, Norman Rosenthal’s landmark exhibition ‘Zeitgeist’ gathered all these international names together for the first time,” he recounted. When he decided to open his own gallery the following year, Beuys connected Ropac with Andy Warhol, who introduced him to Jean-Michel Basquiat. Ropac ended up working with both, bringing them and other American artists to Salzburg where he also showed Beuys, Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and VALIE EXPORT, attracting a loyal German-speaking collector base.

Thaddaeus Ropac with David Hockney and Sydney Picasso. Photo ©Angelika Platen.

But as his roster of artists expanded, it became clear he needed to open a gallery in a major art city, or his artists would take their best work elsewhere. Salzburg, as he found out early on, only comes to life during its summer music festival. “I was here out of a misunderstanding, but it grew close to my heart. I didn’t want to leave Salzburg. Yet I owe a big part of my success to Paris.”

In 1990, he opened his second location in the Marais district of the French capital showing a group of New York artists including Jeff Koons and Haim Steinbach. It was just one year after Jean-Hubert Martin’s groundbreaking exhibition “Magiciens de la terre” at the Centre Pompidou, which looked beyond the Eurocentric art world to show contemporary artists from across Asia, South America, and Indigenous communities. It was a stark contrast in attitude to MoMA’s 1984 “Primitivism” exhibition, and for Ropac, it came to symbolize the curiosity and openness of the French audience. “It was a life-changing exhibition for me; the French were looking where the rest haven’t looked yet. They were the first to show contemporary Chinese art in Europe.”

Installation view, “1983 | 2023” at Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg. Photo by Ulrich Ghezzi.

Ropac’s work with strong trail-blazing women artists has flown under the radar. His second show there was dedicated to American conceptualist Elaine Sturtevant, who had just moved to Paris. She felt misunderstood in the U.S., and thought the French had a wider intellectual access to her concepts around appropriation. Across the channel, in London, Ropac had started working with the likes of Gilbert & George, Tony Cragg, Antony Gormley, and Richard Deacon, who became the biggest names of their generation—but he completely missed out on the next one, the YBAs. It wasn’t until much later, in 2017, that he opened his London outpost in Dover street’s Ely House.

Today, the London gallery plays a key role. There’s an entire team dedicated to forging new artist representations, led by former Serpentine director Julia Peyton-Jones. Since she took the position in 2017, coinciding with the opening of the London location, the gallery’s roster swelled from 60 artists and estates to some 72, taking on a younger generation including Alvaro Barrington, Mandy El-Sayegh, and Zadie Xa. “I’m no longer the one dominating these decisions—and it feels good.” Ropac recounts receiving a phone call from Peyton-Jones urging him to hurry to a graduate show, to look at painter Rachel Jones’s work. “We are not the kind of gallery that picks an artist from a degree show, but as soon as I saw the work it was clear to me we had to work with her.”

Installation view, “1983 | 2023” at Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg. Photo by Ulrich Ghezzi.

Having been a part of the art world since the early 1980s, Ropac naturally became the gallery of choice for numerous lucrative estates, including those of Beuys, Sturtevant, James Rosenquist, Warhol, and Robert Rauschenberg, as well as experimental German filmmaker Harun Farocki. However, his success was not only about being at the right place at the right time. Ropac is driven by genuine curiosity and possesses an uncanny ability to recognize potential and opportunity in unlikely places. He’s also a perfectionist, describes himself as being “obsessed with the art world,” and is often plagued by insomnia, which he still manages to turn into new opportunity. “I use these moments to read and engage with things outside the art world; it opens other worlds for me, so I’m sometimes almost thankful for it.”

Ropac has developed a strong sense for when and where good art is being made, and why. But he always wisely avoided putting on group shows spotlighting art from certain places, opting instead for a deeper engagement with singular artists. “It’s a gut feeling, something you feel really strongly about,” he explained. That was the case when he started working with Romanian painter Adrian Ghenie. “It grew out of my deep interest in middle-Europe, and his work really stood out.” And in 2021, as the world was reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic, Ropac opened a gallery in Seoul, which expanded to double its size this year. “Korea has one of the most sophisticated art worlds you can imagine. Today, it’s driven by young people, it’s incredibly creative.”

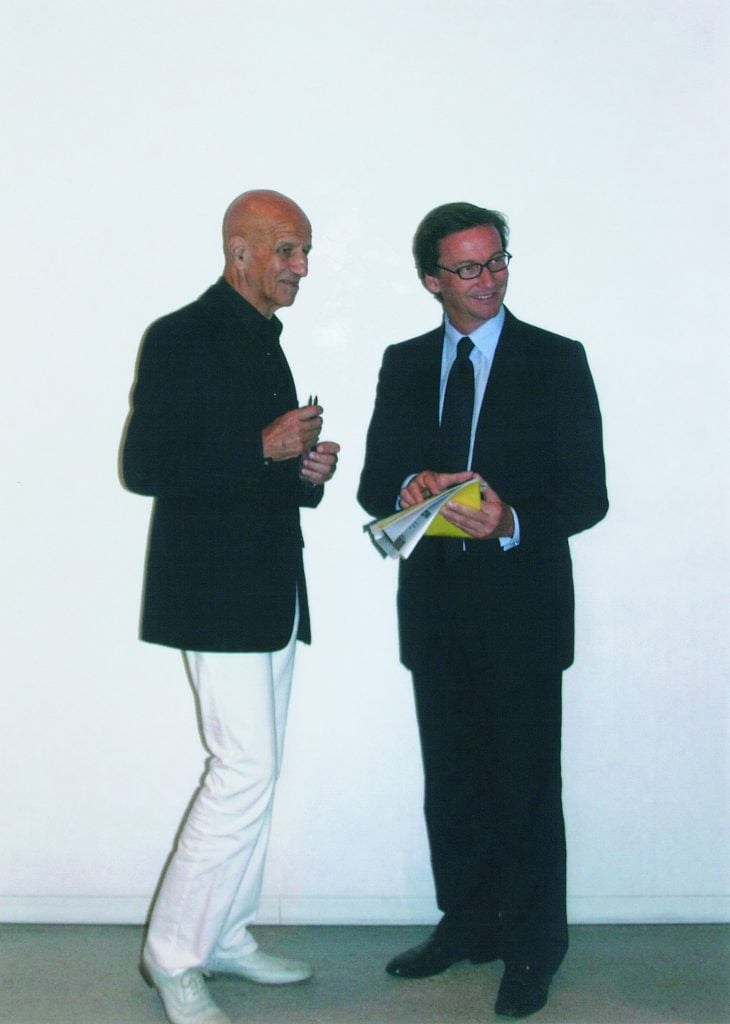

Thaddaeus Ropac and Alex Katz. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul.

Knowing what he knows about the art market, and how different it is from when he first started out 40 years ago, would he would still take the leap today? “Immediately!” he says without hesitation. “I think now, after Covid, is the best time to open a gallery. It was a time for artists to go back to the studio and reflect. I think in the future, we will look back at 2020 as one of the strongest years in terms of art production. Any gallery starting out now already has the fruits of one of the most creative changes in the art world. I wish I were a young gallerist opening in 2023.”

“1983 | 2023” is on view at Thaddaeus Ropac’s Villa Kast and Salzburg Halle through September 30.