Art Fairs

Artbo Marks 20 Years in Bogotá, Celebrating Colombian Creativity From Geometric Minimalism to A.I. Art

The heritage and scope of Colombian contemporary art was on display at the fair.

Walking into the Ágora Bogotá convention center to the sight of the blown-out husk of a car didn’t exactly signal a typical art fair experience. But this striking sculpture set the tone for Artbo’s bold and provocative 20th anniversary. The fair, and the city’s overall art week, proved to be as scrappy, uncompromising, and compelling as ever.

Linda Ponguta’s sculpture greets attendees at Artbo 2024. Courtesy of Espacio Continuo.

Running from September 26 to 29, Artbo is Latin America’s second largest art fair, behind Mexico City’s Zona Maco. But whereas Zona Maco is hot on the heels of the Friezes and Basels on the top-tier international fair circuit, Artbo is much more localized. But it’s anything but provincial.

This year, of the 39 galleries participating, 24 were Colombian. Artbo’s Latin American identity is its strength, and it’s intertwined with Colombia’s rich contemporary art history and vibrant gallery system—a journalist friend also covering the fair noted that the scene recalled Mexico City’s thriving independent gallery heyday a decade ago.

An installation view of the ‘Referentes’ section. Courtesy of Artbo.

That rusted car chassis, sculpted by Bogotá artist Linda Ponguta, makes a strong sociopolitical statement through her signature industrial style. She is part of the roster of Espacio Continuo, a gallery across town in Quinta Camacho.

Ponguta has impressive, more abstract work on view now at the gallery’s current group show, which also features the Chilean artist Mario Opazo’s world map. He carved it directly into the wall, wires dangle from its orifices and drywall rubble is accumulated on the floor. It’s an accurate and poignant reflection of the current state of global affairs.

Mario Opazo, Mapa Mudo # 2 (2016-2024). Courtesy of Espacio Continuo.

The revered 78-year-old polymath conceptualist Miguel Angel Rojas loomed large over the fair. His voyeuristic, clandestine cruising photos from the 1970s are in the Venice Biennale this year, but a hint at his enormous scope was at Artbo.

Downstairs in the ‘Referentes’ section, there is one of his most well known works, David (2005), a sumptuous nude that exudes George Platt-Lynes style queer longing and composition, but then the viewer notices a partial leg is missing and the large-scale photograph doubles as a powerful antiwar missive.

Miguel Angel Rojas, Carbon Carbon III (2024). Courtesy of Galeria La Cometa.

On the main floor, I was repeatedly pulled to Rojas’s Carbon Carbon III (2024), a 3D topographical ecological screed of ash and charcoal on canvas. Barely perceptible gold-leaf animals flee the beautiful squall symbolizing the destruction of the Amazon rainforest.

La Cometa currently has a room in their gallery devoted to the masters and progenitors of Colombian geometric abstract minimalism. Its impressive booth featured lynchpins in the movement like Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar, whose vivid 1954 Composicion Dorada was magnetic, and Carlos Rojas.

Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar, Punto Rojo (1958). Courtesy of Galeria La Cometa.

Another knockout Rojas was exquisitely paired with a striated textured Manuel Hernandez around the corner at the Galeria el Museo booth. At its Bogotá space, upstairs from the exhibitions, is a fabulous hodgepodge of art and design—Yves Klein coffee tables and Andy Warhol Mick Jagger prints mingle with works by Colombian artists like the 79-year-old sculptor Hugo Zapata. There is an assortment of his carved shale and crystal pieces, including a compelling cluster of almost human-sized abstract “flowers” that are topped with pigment.

Works by Manuel Hernandez and Carlos Rojas at Artbo 2024. Courtesy of Galeria El Museo.

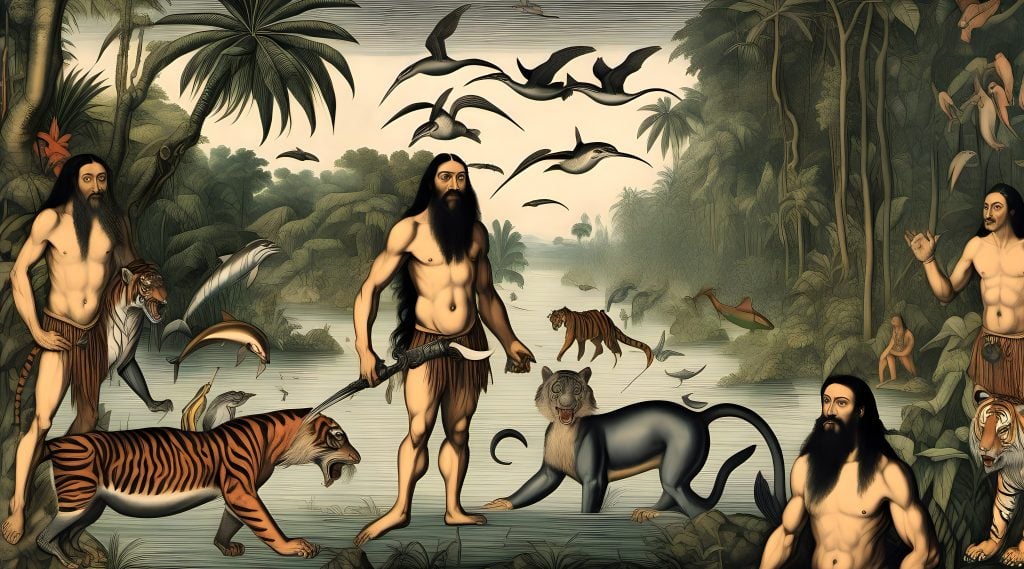

At MOR-Charpentier’s booth, the Bogotá-born, New York-based interdisciplinary artist Carlos Motta proved that doing something wrong can be done so right. His inkjet speculative travelogues are a riff on 16th century Flemish engraver Theodore de Bry’s visual depictions of the Americas. De Bry based his imagery on second-hand information; he himself never visited the “New World” and his often-erroneous embellished engravings greatly skewed and influenced the European world view. Motta flips the script on de Bry’s austere whitewash of the violence of conquest.

Motta’s work is part of his “Discovering the New World” series. He fed an A.I. program a horde of imagery to collate a new reality. The vividly entrancing tableaux are slightly off kilter—a pod of dolphins is flying and one of the loincloth-clad locals has three arms. The more you look, the more you can—Where’s Waldo?-style—find something surreal melded into the scenery.

Carlos Motta, Descubriendo el nuevo mundo (2024). Courtesy of Mor Charpentier.

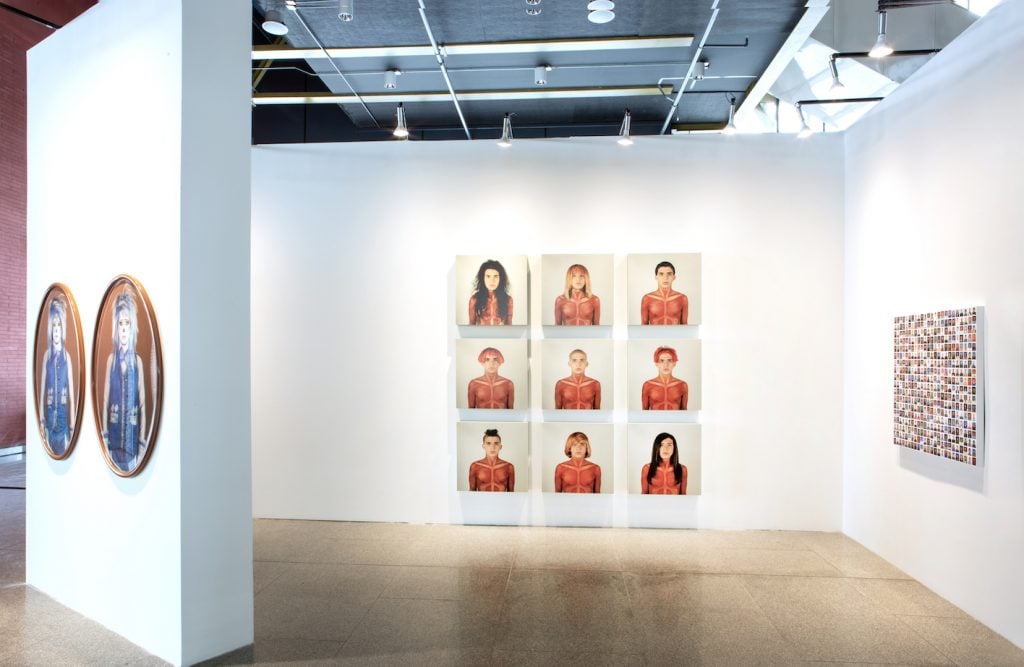

The Berlin-based gallery Klemm’s had a buzzy solo booth with the late Bogotá artist Juan Pablo Echeverri who explored a multitude of guises in his self-portraiture. The gallery showed some of his video pieces, as well as a portion of Miss Foto Japon, his decades-long project of taking a daily photo booth portrait of himself.

“The level and depth of the conversations with both institutional representatives and numerous private collections was remarkable,” the gallery’s founder Sebastian Klemm said. “We have been able to place pieces from all bodies of work on view.”

The Juan Pablo Echeverri solo boot at Artbo. Courtesy of Klemm’s Berlin and The Estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri

A highlight of the week was a special series of guided tours of the artist’s former apartment, “Mansion Echeverri,” that the gallery set up with his estate. Echeverri’s residence was a true extension of his art and the apartment was like stepping in to a habitable art installation. There was his collection of international Eyes of Laura Mars movie posters and his own private photo booth and examples of different iterations of his more than 20 plus year practice.

A view inside ‘Mansion Echeverri’ in Bogota. Courtesy of the Estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri

The artist Evelyn Tovar was on-hand at Otros 360°’s booth. She overlaid a delicate gold leaf utopia and a profound ecological statement atop a bold, bright glaring yellow. Tovar is depicting a real place, but it no longer exists. She bases the works in her “Transitorio” series from postcards she sources from the 1910s-1920s. “This way the place becomes frozen in time,” she said, “eternal.”

Evelyn Tovar’s work is paired with sculptures by Johanna Arenas at Artbo 2024. Courtesy of Otros 360°.

Artbo is on view September 26 to 29 at the Ágora Bogotá convention center.