NFTs

The Artnet NFT 30 Report: Meet the Artists, Innovators, and Collectors Who Built Our New Crypto-Art Era (Part Three)

Discover the people who have created the new NFT paradigm brick by digital brick in part three of our three-part report.

Discover the people who have created the new NFT paradigm brick by digital brick in part three of our three-part report.

Artnet NFT

Who are the figures powering today’s NFT boom? The Artnet NFT 30, sponsored by the APENFT Foundation, offers an introduction to key players.

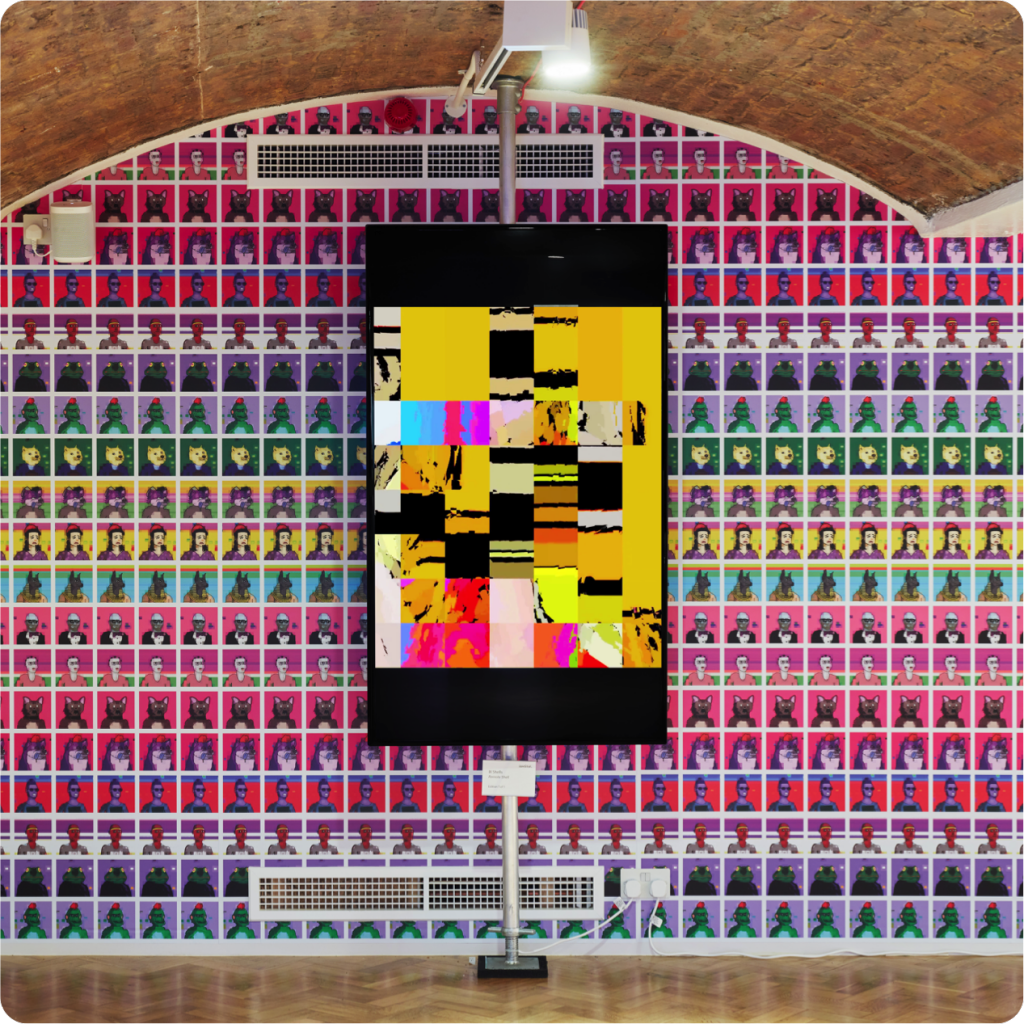

Photo: Courtesy of Institut

With new markets come new opportunities. Not too long ago, Itzel Yard (aka IX Shells) could barely even afford the gas fees for minting her generative art pieces—which prevented her from being able to sell any of them as NFTs at all. Fast forward to this year: in May, she became the highest-selling female NFT artist ever, auctioning her artwork Dreaming at Dusk—a mesmeric piece featuring a swarm of black boxes self-propagating against a whitish-gray backdrop stretching to infinity—for $2 million on Foundation.

The 30-year-old Panamanian artist made the piece in collaboration with the Tor Project, a venerable tech nonprofit that enables protected internet browsing through “onion addresses” (a semi-random sequence of 56 numbers and letters followed by “.onion”). For Dreaming at Dusk, the artist visualized Tor’s first-ever onion domain—created all the way back in 2006—as an NFT, effectively immortalizing it as a major piece of internet history.

Photo: Madison McGaw/BFA.com

Farokh Sarmad Tehrani, known in the crypto space as Farokh.eth, has lost more money in NFTs than the average person will ever hope to spend. In April, the 26-year-old entrepreneur accidentally locked himself out of a MetaMask wallet containing one of the rarest Bored Apes and two M2 Mutant Serums, resulting in a loss of at least 250 ETH (or about $60,000 at the time).

But this experience did little to dampen Farokh’s crypto enthusiasm. The CEO of the digital-forward luxury editorial platform Goodlife Media only entered the NFT space in February of this year, but he has done so with remarkable fervor, and is currently one of the most visible Bored Ape Yacht Club collectors and promoters. (He also owns a CryptoPunk ape as well as 17 Cool Cats, among other holdings.)

But it is as a clarifying voice of the NFT and Web3 frontier that Farokh may be most notable, via Rug Radio—a fully decentralized media company he founded with a focus on rewarding its listeners and creators—and also through his Discord group House of Farokh, which is home to more than 15,000 members who see it as a hub for impassioned discussion. When he’s not on Discord, you can find him on Twitter, where he’s an active presence spreading frequent messages about self-care and positive mental health to the community he cares so much about.

Photo: Courtesy of Kate Vass Galerie

The art dealer Kate Vass remembers a time, back in the crypto-art annus mirabilis of 2017, when the NFT community consisted of a small group of art and technology enthusiasts who yearned for new ways to democratize the art market. When she launched the Zürich-based Kate Vass Galerie that same year—making it one of the first in-person galleries dedicated to the intersection of those two spaces—she struggled to convince collectors to even dabble in the digital realm. The following year, she organized Switzerland’s first blockchain art exhibition, which featured a number of CryptoPunks and a series of tokenized experiences like Sharing Tea, a self-explanatory (and punning) collaboration by Ai Weiwei and Kevin Abosch that they turned into an NFT.

As NFTs continue to spark a speculative frenzy, Vass hopes that her space can keep its focus on the principle that she and other early adopters hold paramount: to give more artists the chance to make it in the art world. And she is not passively waiting for talent to emerge. One of the more highly regarded spotters in the NFT space, Vass is constantly on the lookout for important new artists—and for new collectors she can educate about the history of digital, and particularly generative, art.

Photo: Courtesy of Pak

What is value, where does it come from, and who bestows it? These were the questions at the heart of the Fungible, NFT artist Pak’s much-hyped and highly complex sale at Sotheby’s this April that was part auction, part sweepstakes. The works on offer included thousands of white, digitally rendered cubes sold as “fungible” (or open-source) editions, which came with a proportional number of NFTs; two standalone NFT artworks, The Switch and The Pixel, which were put up for auction on Nifty Gateway; and a quartet of NFTs awarded to individuals who met challenges like posting #PakWashere to the largest social-media audience, or correctly guessing the total value of the auction. In case that was too simple, Pak added an extra wrinkle: buyers could “burn” (destroy) their NFTs in exchange for special “ASH” tokens.

A major success, the event realized a total of $17 million over three days—but it was the result of more than 20 years of digital art-making by Pak, a crypto visionary and founder of both the design studio Undream and the AI platform Archillect. And that was just the warmup: this December, a sale of 266,445 Pak NFTs on Nifty Gateway brought in $91.8 million—possibly making him the most expensive living artist on the primary market.

All the while, the artist has kept their true identity hidden. While Pak is often referred to as an individual, it’s unclear whether they’re a single person or a collective; on Twitter, the bio simply reads: “The Nothing.”

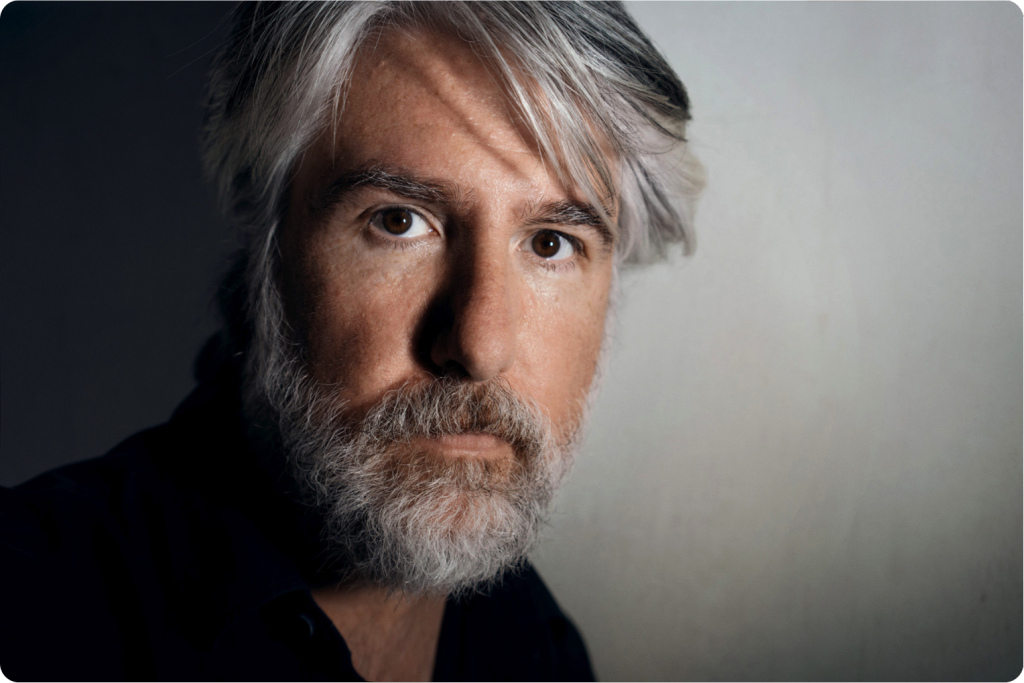

Photo: Courtesy of Studio Kevin Abosch

In what could be seen as a proto-“$120,000 banana” moment, the Irish artist Kevin Abosch made waves in 2016 by selling a photograph of a potato for around $1.5 million. Granted, it was an epic, monumentally voluptuous potato, and CNN dubbed it a portrait of “the most photogenic potato in the world,” but still. Since that transaction put everyone’s focus on money, Abosch began to think of himself “as a coin,” he has said, rather than as an artist. It was the beginning of a journey that led him to integrate cryptocurrencies and the blockchain into his art-making—but also to put a human spin on it.

In 2018, Abosch created 10 million tokens on the Ethereum blockchain and stamped addresses corresponding to the tokens on paper, using his own blood. He titled the series “IAMACOIN,” describing it as “100 physical artworks and a limited edition of 10 million virtual artworks” and using the physical articulation of blockchain addresses to allow him to scrutinize the nature of the crypto economy. Also in 2018, he sold a yellow neon physical version of a crypto address he made that references “#lambo”—a hashtag crypto investors use in chat groups to boast about their winnings—for more than the cost of an actual Lamborghini.

How much will people pay for something? And why? In the end, Abosch’s approach is all about exploring how humans interact with goods in a space where establishing value is still, truth be told, a work in progress.

Photo: Courtesy of Kate Vass Galerie

Giving up control of your art is scary for most people—but for artist Helena Sarin, that’s the most exciting part. A pioneering AI artist with a background in both software engineering (she worked at the fabled Bell Labs) and traditional art-making, Sarin had long kept her twin passions separate until she discovered GANs, the shorthand term for Generative Adversarial Networks, which process various data sets to produce unpredictable “outputs.” Typically, GANs have been used to process raw inputs like photo databases to create unreal portraits, but Sarin saw the opportunity to take a more personal route. Feeding her own drawings into the networks, she makes outputs—released as NFTs—that are, uncannily, a true duet between herself and the machine.

Today Sarin is regarded not only as an artist but as a deep thinker on the subject of AI, and her volume The Book of GANesis: Divine Comedy in Tangled Representations, from 2019, is regarded as the first-ever AI art book. As for the human role in the future of the genre, however, Sarin is less than sanguine. “Autonomous machine art is looming, and generative models trained on all art history will soon be able to produce imagery in every style and with high resolution,” she has said—a development that promises to render even GANs as we now know them to the dustbin of history.

Photo: Joe Schildhorn/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images

A longtime digital artist (as well as art critic, curator, collector, teacher, and what he terms “dealer-to-dealer dealer”), Kenny Schachter fell hard for NFTs the moment he heard about them—and then fell even harder when, last year, he minted some of his own work and sold

it for $4,000 on Nifty Gateway. The money caught his attention, but it was more than that. A longtime champion of ahead-of-their-time artists like Vito Acconci and Paul Thek, whose vital but not easily classifiable work never found a market during their lifetimes, Schachter saw the possibility for an enormous new marketplace that could encompass a whole range of experimental artists—and, at the same time, build a community that was more welcoming than the snobbish art world.

Overnight, Schachter became a vocal advocate for NFTs, reinventing himself as the art world’s “NFT whisperer” via his monthly column on Artnet News, social media, and the lecture circuit (including a barnstorming video presentation he gave on NFTs to the School of Visual Arts). He has also organized a string of art shows on the subject at such venues as Cologne’s Nagel Draxler Gallery and Vienna’s Galerie Charim. Then, there was that time he helped Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Jerry Saltz mint an NFT… but that’s another story.

While Schachter’s apostolic championing of “NFTism”—a term he not only coined and trademarked, but had tattooed on his bicep—has, in typical Schachter fashion, inspired a barrage of hate from crypto critics, this has only tightened his resolve on NFTs, intent on changing the hearts and minds of the skeptics. Schachter wants the revolution to succeed, if only so he doesn’t have to “jump back on the hamster wheel chasing art fairs and auctions to make a living,” he has written. It’s working out so far: to date, if you count his active secondary market, his NFTs sales have totaled well into the millions of dollars.

Photo: Courtesy of ClubNFT

In the sea of art critics who have engaged with the rising NFT movement, Jason Bailey stands out as an uncommonly prescient champion. On his highly regarded art-meets-tech blog Artnome, Bailey prophesied the imminent debut of a blockchain-based art market way back in 2017. In the years since, he has been credited with raising awareness around AI art in the context of the crypto community, as well as popularizing NFTs in the traditional art sector.

But Bailey is not only an art critic—he is also an active participant in the market. In fact, he was the first-ever collector on SuperRare, and soon thereafter joined forces with the digital marketplace to connect it with NFT artists, as well as with the art establishment. In November, Bailey became CEO and cofounder of the brand-new ClubNFT, an organization “building the next generation of solutions to discover, protect, and share NFTS,” as well as founder of GreenNFTs, an initiative promoting eco-friendly means of minting crypto artworks, which is notoriously energy-intensive.

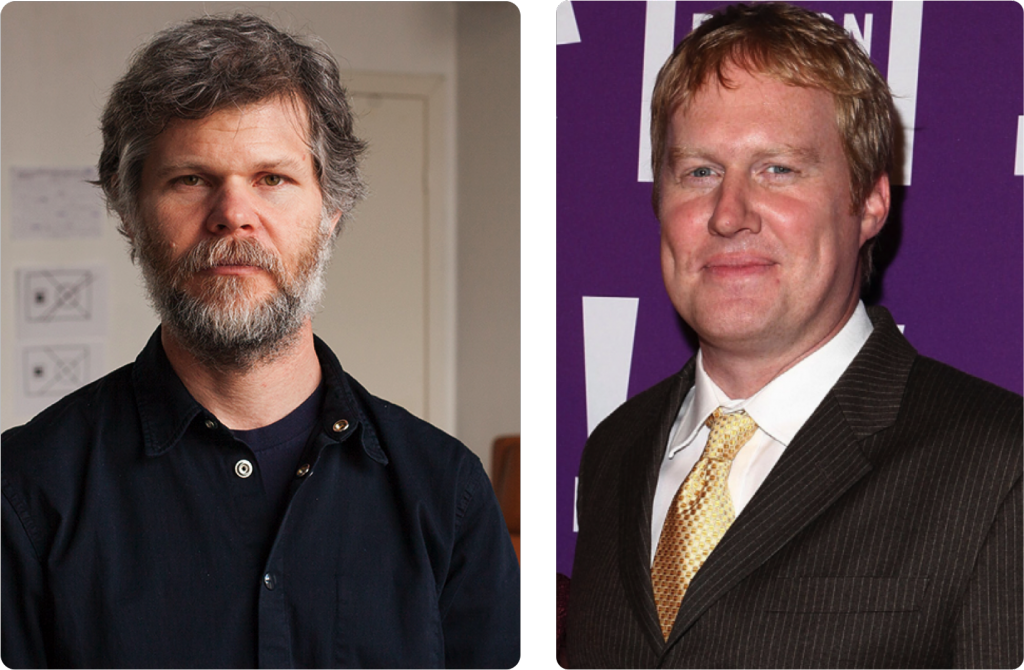

Photos: Andrey Noskov/Wikimedia Commons; Lisa Hancock/WireImage

Twenty years ago—a millennium in the NFT context—the MIT Media Lab scholars Ben Fry and Casey Reas created Processing, a free programming language intended to make it easy for visual artists to navigate computer programming and coding systems in a way that allowed them to do creative work in the digital arena.

Since then, Processing has become a touchstone for the visual arts community, adopted by artists and designers across the globe and treated as essential training in art schools. Its simple introduction to complex technology has also endeared it to everyone from journalists at the New York Times and Nature to the band Radiohead, who used Processing to create their 2007 “House of Cards” music video.

Today, Reas—an artist himself and professor at UCLA—and Fry continue to onboard new creatives into the digital realm via the Processing Foundation, an organization founded in 2012 that is dedicated to connecting artists with tech pioneers, most recently in the NFT space.

Photo: Courtesy of 4156

Going by the pseudonym 4156 in tribute to their favorite Punk (a blue-bandanna-sporting ape, which they once embellished with a pair of chunky glasses for their Twitter avatar), this enigmatic collector has managed to make major waves in the crypto sphere within mere months. Since buying 4156 for 650 ETH ($1.25 million at the time, then the most expensive Punk ever sold) in mid-February and joining Twitter shortly thereafter, their account has garnered more than 98,000 followers, attracted to their vocal boosterism of CryptoPunks and the implications they have for the metaverse.

With a professional background in tech, art, and finance, 4156 has interests in the

NFT space that stretch beyond Punks—this March, they purchased London-based crypto-art pioneer XCOPY’s Death Dip for $1.58 million, calling the spooky GIF of what looks like the grim reaper awash in code the “most important piece” by “the most important living artist.” The following month, they bought Pepe the Frog creator Matt Furie’s “Feels Good Man” Pepe NFT (aka the Genesis Pepe) on OpenSea for 420 ETH (then about $1 million) and proclaimed to be “overwhelmed by the privilege of owning the piece, and overwhelmed by the responsibility of safeguarding it.”

It’s clear 4156 has their eye on the history books. Referring to their entire NFT holdings

by the same name, they have said they consider themselves “a temporary steward and financial beneficiary” of the collection. “If I do a good job, I hope 4156 will survive me. I hope she will eventually be owned by the whole community.”

One NFT the collector no longer needs to steward is their namesake, CryptoPunk #4156. This December, they offered up their signature ape in a surprise flash sale, starting at 4,000 ETH and lowering the price by 500 ETH increments every hour or so. Ultimately, it sold for 2,500 ETH ($10.4 million at press time)—marking a new chapter for the mysterious Punk aficionado.