The Art Detective

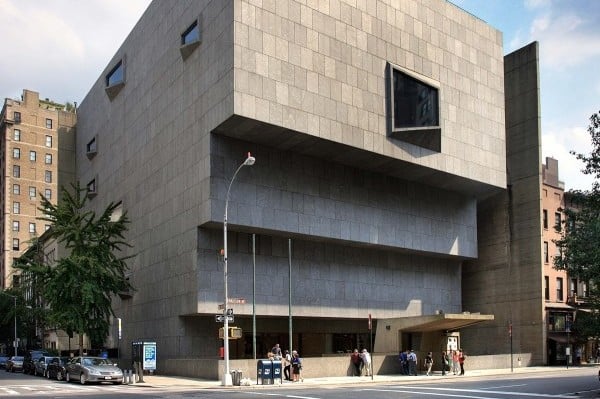

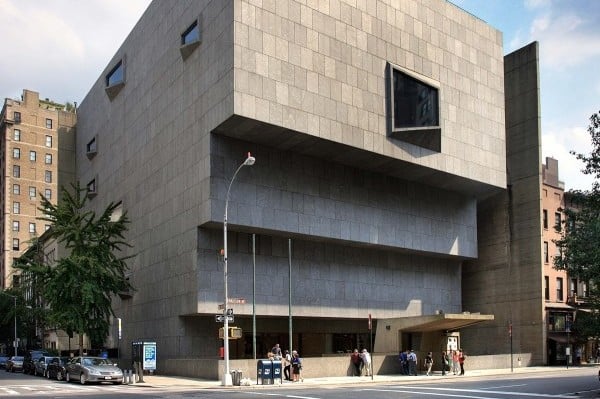

The Whitney Is in Talks With Suitors Who Want to Buy the Breuer Building. Who Will Win the Prize?

The landmark's history—and quirks—make it an attractive target for a specific kind of buyer.

The landmark's history—and quirks—make it an attractive target for a specific kind of buyer.

Katya Kazakina

The Whitney Museum of American Art is in talks with multiple entities about selling off its crown jewel, the Breuer building at 945 Madison Avenue, the Art Detective has learned.

The art world is abuzz.

Designed by Marcel Breuer, the building that has housed three major New York museums has an irresistible built-in provenance. The Whitney’s home for almost five decades, from the mid-1960s until its move to the Meatpacking district downtown, the Breuer welcomed the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2015 to show Modern and contemporary art. But running it proved too costly, and the Met subleased the building to the Frick Collection, which has displayed Titians and Rembrandts on its concrete walls since 2021. The Met’s original lease was for eight years, and the Frick extended the arrangement for an additional year. It will bid the Breuer adieu after its final exhibition ends March 3, 2024.

It’s intriguing to imagine who will end up in those art-history-oozing walls. In recent years, the building has been considered by the Calder Foundation and Phillips (prior to the auction house’s move to 450 Park Avenue), according to people familiar the matter.

Flora Whitney Miller, president of the Whitney Museum of American Art, cuts the ribbon during the dedication ceremony for the museum’s building. Looking on are (from left): the building’s architect, Marcel Breuer; Mrs. John F. Kennedy; Lloyd Goodrich, director of the museum, and architect Hamilton Smith.

“The Nahmads could buy it and build the best family apartment on the top two floors and have the bottom floors for a gallery, or Larry could buy it,” said an art-business executive. “It’s nothing for Hermès or Dior to buy it and have their showrooms there. Think if that was a store for LVMH or Valentino. It’s entirely credible. What a great space.” The executive added that it could also serve as the dream acquisition for a top art collector: “I can see a private museum for anyone who has a $1 billion collection, which is increasingly more people these days. Someone like Stevie Cohen.”

Indeed, stepping inside the building can cast a spell on those with a yen for real estate and a love of art. The possibility of showing and selling artworks at the Breuer wowed Sotheby’s senior staff, for instance, who have toured the place.

“It’s the ultimate,” said an executive of a rival firm. “We all are trying to create this museum-like experience.”

When asked about the lineup of suitors, a spokesperson for the Whitney would only say that the museum “is exploring options for the Breuer building when the current arrangement with the Met and the Frick expires in 2024.”

The Met Breuer. Photo: DON EMMERT/AFP/Getty Images.

There are significant hurdles for any transaction.

Selling the building would require the approval of Leonard Lauder, the Whitney’s biggest benefactor, who attached some heavy strings to his $131 million gift to the museum in 2008: The Whitney would have to hold on to the Breuer building “for an extended” yet unspecified period, the New York Times reported at the time. Lauder worried that the museum’s move downtown would prove to be a fiasco, and he wanted to make ensure it could return uptown should the need arise, according to people familiar with his thinking.

Representatives for Lauder didn’t respond to emails and calls seeking comment.

It appears things have changed. The Whitney’s arrangement with the Met created a natural eight-year buffer for the sale of the building. At the end of the term, the Met had an option to lease again, buy, or walk away, according to a person familiar with the deal. “There were no restrictions that would stop the Whitney from selling” the Breuer thereafter, the person said.

Installation view, “Gerhard Richter: Painting After All at the Met Breuer, 2020. Photo: Chris Heins, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Breuer’s landmark status is another challenge.

“Everything that makes the Breuer so special—its museum status, landmark designation, and location in the Upper East Side historic district—will be a hurdle for a potential developer, requiring zoning changes and likely sparking fierce community opposition,” the Art Detective wrote in September 2021. Nothing has changed in this respect.

The original 82,000-squаre-foot floor plan included five floors, with 26,700 in net gallery space, 21,500 square feet of storage, and 12,200 square feet of office space (which was reduced when the fifth floor was converted into galleries). On the fourth floor, the ceiling measures about 17.5 feet, the highest in the building.

Installation view of Giovanni Bellini, The Ecstasy of St. Francis (c. 1480) at the Frick Madison. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

The Breuer building’s value is another big unknown. Landmark museum buildings don’t come up for sale very often, so its value is hard to determine, according to real estate brokers. Most developers might see no value at all, given all the limitations and the current banking crisis.

The closest comp is almost a decade old: In 2014, the landmark 45,000-square-foot former church near Gramercy Park sold for $50 million (or $1,111 per square foot) and is now the private museum Fotografiska; it was offered on the market last year at $135 million. This year, the landmark Flatiron Building drew a $190 million bid in a court-ordered auction, but the buyer later reneged, and the 255,000-square-foot building is returning to the auction block next month.

Fotografiska. Photo courtesy of Fotografiska.

So, how much could the Breuer cost?

“I wouldn’t put any number on something as quirky as that,” said Nat Rockett, a commercial real estate broker in Manhattan. “It’s useful to a very specialized audience. And you have to find someone in that audience who wants to buy it.”

If Sotheby’s, owned by billionaire Patrick Drahi, were in fact to pounce on the Breuer building, it would mark a return to Madison Avenue for the auction house. After purchasing Parke-Bernet Galleries in 1964, Sotheby’s of London spent two decades at 980 Madison Avenue (currently the headquarters of Gagosian gallery). In 1987, the building was sold, and Sotheby’s moved to York Avenue.

That building, at 1334 York, has 407,259 square feet over 10 floors, eight loading docks, and an outpost of Sant Ambroeus restaurant. It looks spiffy after a $50 million renovation in 2019, which expanded galleries and addressed many old concerns.

Sotheby’s headquarters on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Despite the pricy facelift, Sotheby’s has been investigating potential options for expanding its real estate footprint, according to people familiar with these plans. And there are indications that Team Drahi is thinking outside of the box.

In January 2022, Sotheby’s bought a converted manufacturing building in Long Island City, Queens, for $82.5 million. Known as Gantry Point, it has 240,000 square feet of commercial space and was refurbished in 2021 by the design firm Studios Architecture. It includes a two-story base and a nine-story tower with Manhattan skyline views, high ceilings, industrial vibe, and a roof terrace on the eighth floor.

Fast-spreading word about the Whitney’s negotiations, and the potential of a high-profile new tenant at the Breuer building, has sparked excitement among those in the Upper East Side art world—particularly if Sotheby’s should indeed emerge as winner of the prize. A representative for Sotheby’s declined to comment.

“I think it would be great if they did,” said art dealer Bill Acquavella, whose stately quarters occupy a mansion on East 79th Street just off Madison Avenue. While not revolutionary, he said, the move would result in “more interesting art for people, more access, easier to get to. I certainly would like it because it would be very convenient for me. In that sense I am all for it.”

Alberto Mugrabi, whose family office is moving to East 77th Street from midtown, said it would be an “unbelievable” development.

“They’ll be in the middle of all the art world,” he said. “You are in the museum district. What’s better than that?”

Any new occupant, meanwhile, will join a wave of buzzy new arrivals, including White Cube gallery and London private club 5 Hertford Street, as well as Miami’s art-world favorite restaurant, Casa Tua. Fleiss-Vallois, a partnership between two Paris-based galleries, Galerie 1900-2000 and Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois, is opening on Madison Avenue at East 79th Street in May.

“The old uptown is getting a new life,” Mugrabi said.