Beyond an elevator wallpapered with hacker mantras like “you can’t spell culture without cult” and “fear kills growth” was a gray cement basement where two associates from Bright Moments Gallery guarded an iPad that was the key to owning a Tyler Hobbs original. The artist was upstairs with the live band, catered sushi rolls, and champagne. Dozens of NFT artworks generated from his algorithm were presented to the New York gallery’s applauding crowd, while collectors moved downstairs to point-and-click their way into the digital art collect-athon.

The “Incomplete Control” exhibition happened nearly a year ago when speculators turned NFTs into a $60 billion market as the price of cryptocurrencies shot through the roof and public interest in these blockchain-based collectibles spiked. That December evening, collectors had swiped about $7 million in artworks, which made Hobbs feel like he had really made it.

“Digital art was usually a sentence of poverty,” he later explained in an interview with Artnet News. Nowadays, it’s his bank account, a vehicle of celebrity, and an opportunity to make history.

There are only a handful of digital artists who have survived the crypto crash and the plummeting sales records from the NFT market. Hobbs has distinguished himself as one of the few artists to emerge relatively unscathed with a flock of faithful collectors from the tech world and the stamp of approval from the traditional art world. Next year, he will exhibit physical works at Pace Gallery, as more galleries are selling NFTs and major museums are putting digital art in their lobbies.

“This has been the longest year of my life,” Hobbs said. “But thankfully, it has been almost entirely positive.”

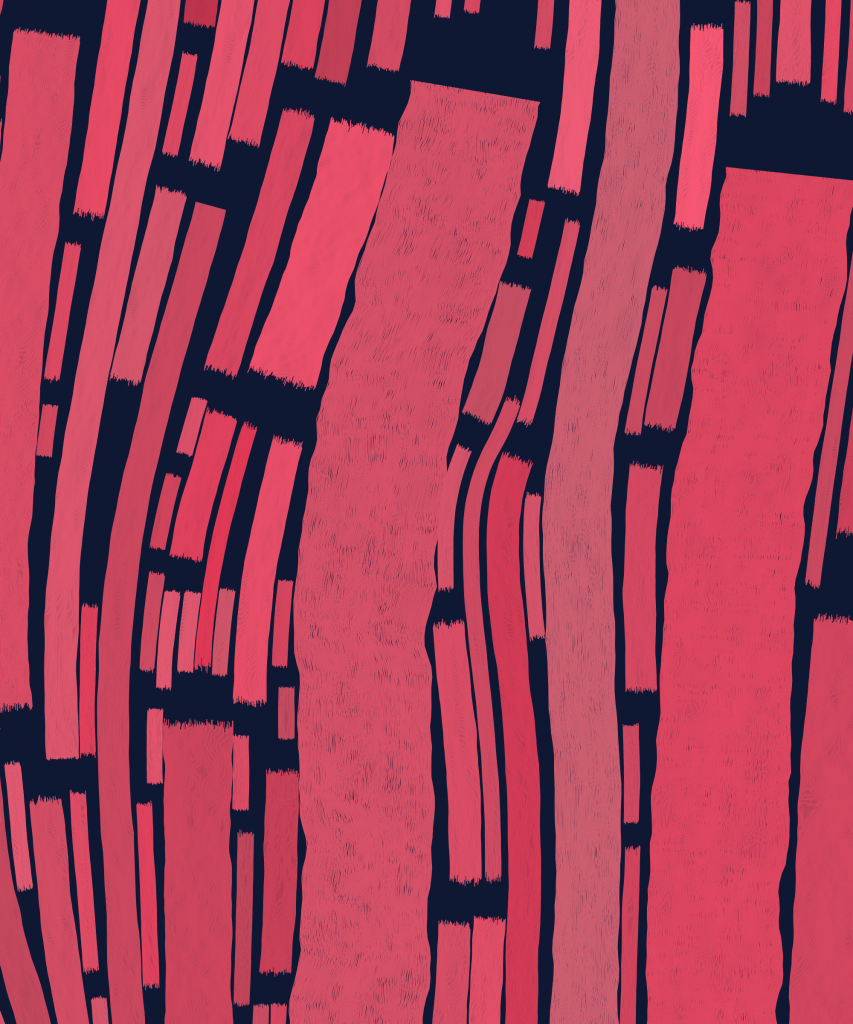

Tyler Hobbs’s Fidenza #61. Minted on 11 June 2021. Courtesy the artist and Phillips.

Most collectors know Hobbs because of Fidenza, a series of 999 NFTs generated by a computer algorithm that he coded to produce images that resemble Mondrian paintings—that is, if the Dutch artist had taken a squeegee to the canvases while the paint was still drying. In August 2021, Starry Night Capital splurged on Fidenzas, spending nearly $5 million in a buying spree that increased the floor price of the artworks over the next month by 12 times its previous value to nearly $900,000. Months later, the artworks purchased by Starry Night were the subject of a bankruptcy scandal tied to the collection’s hedge fund owner, Three Arrows Capital. In October, a liquidator took possession of the Fidenzas.

Within the traditional art world, being associated with a bankruptcy worth $3.5 billion might doom an artist’s market to the dumpster; however, the crypto art world largely rewards those in proximity to spectacle and risk. Hobbs also resists the idea that he must rationalize how collectors financialize his NFTs.

“I don’t lose sleep at night thinking about who owns my artworks,” Hobbs explained. “Someone in the traditional art world is probably used to working closely with a gallery and exerting control over who collects their work. A fact of life with NFTs is that you don’t have that kind of control. It’s much more open to the market, for better or worse.”

Hobbs, 35, only started considering himself an artist in the last decade. He worked for years as a software engineer at a local startup in Austin, Texas that built open-source tools and distributed databases. His artistic training came from private instructors and online classes. Then he started applying his knowledge of writing code to his practice. As early as 2014, he was blogging about his discoveries, which often included graphs where he attempted to chart the relationship between randomness and polish in artistic output—everything from the 19th-century paintings of William Adolphe-Bougeureau to the 21st-century tunes of the Backstreet Boys.

“Not only is it easy to introduce randomness at any point in the composition, but the randomness itself can be controlled in many ways,” he wrote. “In some ways, the artist is merely setting up a perfect environment to discover great works of chance.”

Seeing him interact with fans during the Art Blocks weekend in Marfa, Texas earlier this month, Hobbs kind of looked like a Backstreet Boy. He wore a wide-brimmed hat, wire-framed glasses, and a sweater featuring Raymond Pettibon’s artwork for Sonic Youth’s 1990 Goo album. During the weekend parties, Hobbs was often flanked by his crypto groupies, mostly young men in their 20s and 30s, eager to learn what’s next from their idol.

“Tyler Hobbs is an artist who was dedicated to this craft when generative art was a relatively niche medium,” said Erick Calderon, the founder of Art Blocks, an NFT marketplace that served as the platform for Hobbs’s breakthrough Fidenza series. “His art has a formality and simplicity that is instantly recognizable and understandable, something that I think is insanely difficult to achieve.”

Some buyers describe collecting the artist’s work as an obsession. Andrew Badr lost his software engineering job last year during the pandemic. “I found myself with all this time and energy that ended up going into the world of NFTs,” he told Artnet News.

An episode of the crypto investor Kevin Rose’s podcast spoke about the token boom, and Badr, who tinkered with digital art in the past, started paying attention. Hobbs was a clear standout so the new collector bought into his work. Badr now owns more than 20 Fidenzas, having sold a handful during the bubble. His collection has grown to include nearly 500 NFTs, including works by Dmitri Cherniak, Emily Xie, and Matt DesLauriers. The collector has also become a creator, producing a generative art series of typographic NFTs with the artists Emily Edelman and Dima Ofman.

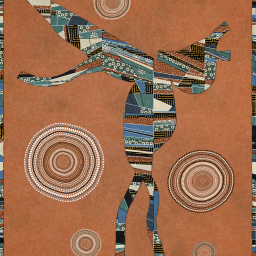

Tyler Hobbs, QQL (2022). © Tyler Hobbs, courtesy Pace Verso.

One might say that Hobbs has a generative effect on collectors like Badr, inspiring them to create their own artworks. His upcoming exhibition at Pace Gallery in April 2023 will feature nearly a dozen paintings based on his latest series QQL, a collaboration with another artist named Dandelion Wist Mané, which allows buyers to indirectly tweak the algorithm until they are satisfied with the randomly-generated results. Collectors who mint artworks also receive a two percent royalty on secondary sales, which Hobbs said was his way of recognizing their contributions to the creative process.

The QQL release defied expectations of the bear market with collectors spending $17 million on nearly 1,000 minting passes. A month later and buyers had built a $28 million secondary market—a shocking statistic when trading volumes had fallen 97 percent elsewhere in the NFT world. Sales have since slowed as collectors use the minting passes to produce artworks. When this happens, Hobbs often likes to highlight their creations on social media.

“The thin lines really allow the colors to blend, creating a nice richness in perceptual color,” Hobbs recently wrote about a purple QQL made by Thomas Lin Pedersen, another generative artist.

But the artworks included in the Pace Gallery exhibition will be entirely hand-painted by Hobbs. The exhibition was the result of a meeting over the summer between the dealership’s digital stratego, Ariel Hudes, and the artist, who met during a Pace Verso event for the release of John Gerrard’s recent NFT project, Petro National. Hobbs had remained skeptical about the traditional art world, but the exhibition impressed him.

“Tyler represents an upper-tier of the NFT market that is similar to what a Pace Gallery artist represents in the physical art market,” Hudes told Artnet News, explaining why she thought Hobbs was ready for his debut with the megadealer. “He is the one defining this space.”

Not that Hobbs necessarily needs the money. His secondary sales have made him a millionaire several times over. When asked how long his Austin, Texas studio with five employees could run if he never sold another artwork again, he did a quick calculation.

“Without selling anything? We could go full throttle for decades.”