Art Fairs

Don’t Miss These Unbelievable Installations at SPRING/BREAK

From therapy sessions to a museum dedicated to a 2000 hit, it's all here.

From therapy sessions to a museum dedicated to a 2000 hit, it's all here.

Sarah Cascone

Spring was in the air in New York on the last day of February—unusual for Armory Week, when the weather tends more to blustery winds and even snow—as art lovers made their way to Times Square for the opening of the sixth annual SPRING/BREAK Art Show.

Co-founded and directed by husband-and-wife artist team Andrew Gori and Ambre Kelly, the fair was inaugurating a new location, inside the former Vanity Fair offices in the old Conde Nast building at 4 Times Square. When I arrived early in the afternoon, I had trouble finding the entrance, but there was a line around the block by the time I left midway through the VIP opening.

SPRING/BREAK is known for turning historic venues into unexpected art destinations, getting its start at the former St. Patrick’s Old School before a two-year run at the decommissioned 34th Street post office at Skylight at Moynihan Station. Its new home may seem more corporate and modern, but what it lacks in internal character was made up for by the views, which surround visitors with Times Square both old and new, from LED signs to the New Year’s Eve ball.

Greg Haberny. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

The fair’s other strong point is its curatorial focus, which brings offbeat work to the fore. I hate to rely on words like wacky or zany, but if they apply anywhere during Armory Week, it’s here.

Beginning with the entry ways on both floors—which featured an impressive array of small hanging sculptures by Greg Haberny, created from fragments from his cut-up paintings, on 22, and Michael Zelehoski’s “Resonance Structures,” large geometric works from repurposed scaffolding pipes, on 23—SPRING/BREAK is full of exciting, often-immersive installations that go way beyond the white cube presentations you might be used to at art fairs.

Jack and Leigh Ruby, Barbershop. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

1. Jack and Leigh Ruby, Barbershop, curated by Eve Sussman and Simon Lee

All is not what it seems in booth 2225, where an elaborate barber shop tableau in the front room gives way to a stark control room featuring a sound mixing and editing station and numerous video monitors streaming footage from around Times Square.

That’s because “this is the subterfuge,” explains Leigh Ruby, who created the “surveillance theater piece” with her brother Jack. The end product was being created on site in the back room, as the duo listened in on anonymous actors wearing earbuds as well as unsuspecting passersby making their way through Times Square below.

Jack and Leigh Ruby, Barbershop. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

As one of the only works I spotted that responded directly to the fair’s new setting, it reminded me of a piece by Violet Dennison and Coco Young at last spring’s Work in Progress Artist Residency, organized by collector Tiffany Zabludowicz in an empty office space at nearby 1500 Broadway. Like the Rubys, they capitalized on the hustle and bustle of the busy intersection, using a long-range paparazzi lens to film the comings and goings far below in Times Square.

Barbershop, of course, is far more layered, from the carefully considered details of the shop up front, to the live editing taking place behind the scenes.

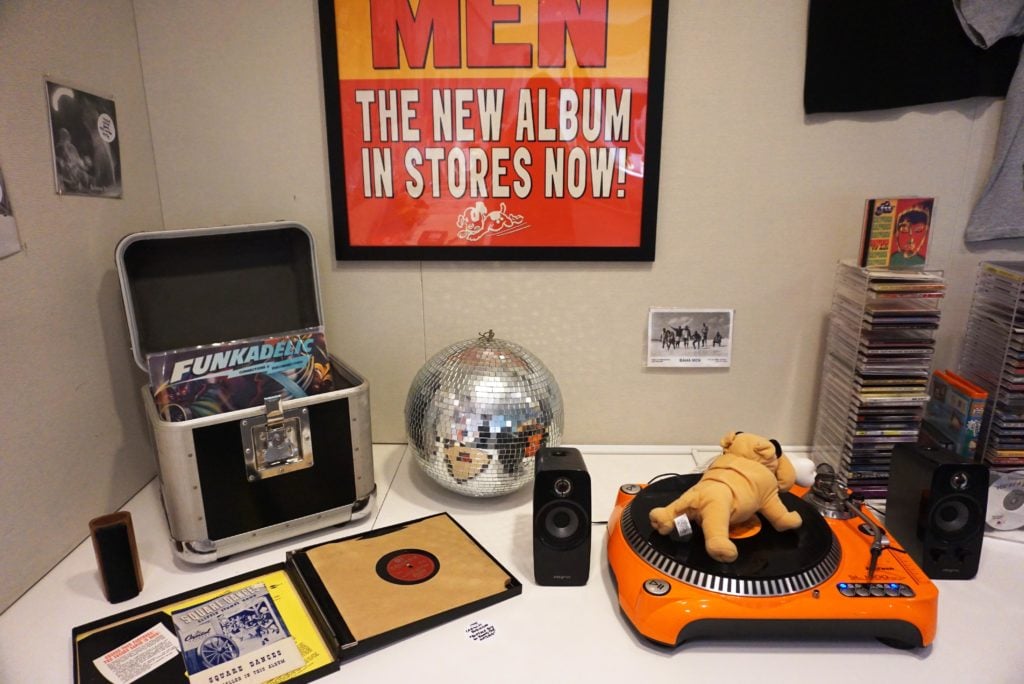

Ben Sisto, The Museum of Who Let Who Let the Dogs Out Out?. Courtesy of the Midnight Society.

2. Ben Sisto, The Museum of Who Let Who Let the Dogs Out Out?, curated by Jac Lahav

No, that’s not a typo with the doubling. For the last seven years, artist Ben Sisto, indulging his interest in copyright law and intellectual property issues, has been obsessively researching the highly contested origins of the unforgettable, arguably annoying hook from the 2000 Baha Men hit Who Let the Dogs Out?

The result, on view at booth 2208, contains LPs and CDs, as well as t-shirts, stuffed animals, and other merchandise connected to the song. There’s even a “Who Let the Mets Out?” pin based on a second version recorded by the band in honor of the New York Mets’ 2000 World Series bid.

The first person to record the catchy refrain might have been a feminist singer named Gillette, best-known for her song Short Dick Man, on the 1994 track “You’re a Dog,” but Sisto’s latest research has led him to Miami Boom Productions, who are claiming the credit. The artist plans to have two floppy discs that supposedly contain the original recordings of their demo “The 2,” forensically analyzed to determine their date of origin. (After a 15-year separation, the DJ duo reunited to play last night’s SPRING/BREAK after party.)

While Sisto is selling limited-edition items based on his collection at the fair, he told me that he’d only part with the museum in its entirety “if someone offered me an amount of money that I couldn’t turn down.”

Amie Cunat, Church. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

3. Amie Cunat and Kat Chamberlin, “C + C,” curated by Nicholas Cueva

Throughout the fair, curators have been encouraged to transform the bland office spaces. One particularly successful attempt to do so can be found in the opening space for Amie Cunat and Kat Chamberlin’s two-person show “C + C.”

As a lead-in to Chamberlin’s obsessive pencil drawings, Cunat—who, full disclosure, I studied art with at New York’s Fordham University—has executed a colorful mural across half the space, including a temporary wall that bisects the space, diving the presentations by the two artists. The work, titled Church, serves as a bold backdrop for her grid-like wall sculptures, which seem to float in the space.

It’s a site-specific installation, as Cunat has adapted the design to fit the parameters of the room at hand, but the piece is also available for sale, to be installed in the space of your choosing.

Ray Lee, NDD Immersion Room. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

4. Ray Lee, NDD Immersion Room, curated by Amani Olu

At Ray Lee’s NDD Immersion Room, visitors walk up to a medical office desk swathed in green light, and surrender their phones, placing them in a lockbox before entering the immersion room. (Don’t worry, there’s a hammer to smash the glass and retrieve your phone if the separation is too much.)

Upon entering the darkened room, flashlight in hand, patients find themselves transported from the heart of Times Square to an isolated wood, fragrant with the scent of pine trees and fallen oak leaves. It’s a restorative experience, and utterly unexpected.

The piece is a treatment for a condition the artist has dubbed “Nature Deficit Disorder,” which he described as “a fictive medical diagnosis for the very real effects of too much screen time.”

Upon completion of your visit, you can get a signed certificate acknowledging that you’ve successfully undergone the therapy. Lee will even email you the footage of your time inside the room.

I especially recommend a visit if you, like me, often find yourself woozy after a spin through artworks accessible only through virtual reality headsets, of which there are at least two at the fair.

Lisa Levy, Mental Health Intake Form. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

5. Lisa Levy and Paul Gagner, Mental Health Intake Form, curated by Paul D’Agostino

Also taking a therapeutic approach was Lisa Levy—whom you might have spotted mocking Marina Abramović with a naked performance art piece in 2016—with a new piece titled Mental Intake Form, part of her installation “Take Us Lying Down,” with painter Paul Gagner. The office space, with its built-in reception desk, lent itself perfectly to the conceit, with a sign-up sheet for therapy sessions, which took the form of performances.

The work begins with an intake form with questions like “What’s your favorite word?” and a classic math problem about two drivers traveling at different speeds. You’re also asked whether you have “funny-looking birthmark(s),” rabies, or “fear of cyborgs.”

When I stopped in, Levy was just starting a session with a 30-year-old man who had just moved back to the city after getting married. At first, as he described his life, she wondered why he would seek out therapy when everything seemed to be going so well.

Later, as he explained several career changes, she asked if perhaps he wondered how far he might have advanced if he had stuck with his first path in government. “You’ve hit on something there,” he admitted.

LeRone Wilson, Ancestral Hive. Courtesy of the artist.

6. LeRone Wilson, Ancestral Hive, curated by Katya Valevich

One of the more sensory experiences on offer is stepping into Ancestral Hive, a large-scale recreation of a bee hive by LeRone Wilson, who creates stunning encaustic works with wax. The sweet-smelling enclosure is bright yellow and honeycombed, reflecting the impressive natural creations of the honeybee.

In his work, Wilson replicates their process, combining wax with the same sort of resin used by bees to build their hives.

Ancestral Hive resonates all the more deeply in the setting of a maze-like corporate office, where employees are all too often reduced to busy worker bees.

Valery Jung Estabrook, Hometown Hero (Chink). Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

7. Valery Jung Estabrook, Hometown Hero (Chink), curated by Debbi Kenote and Til Will of Open House

Southern comfort is anything but comfortable in Valery Jung Estabrook’s Hometown Hero (Chink), a full-scale living room replete with a working TV, displaying the artist’s video work.

“Valery is from the South, so there’s definitely a critique of Southern culture, but she’s also Korean-American,” said co-curator Debbi Kenote of the piece, which attempts to reconcile this dual identity.

The soft upholstered surfaces of the work belie the deep-seated, destructive force of racism associated with the Confederate flag, which boldly decorates the room’s cushy reclining chair.

Cate Giordano, TV Guide. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

8. Cate Giordano, TV Guide, curated by Suzanne Kim

Also in the “home interior” vein was Cate Giordano’s TV GUIDE, inspired by the Pensacola, Florida, home of her grandmother. Crafted from cardboard, news paper, papier-mâché, duct tape, styrofoam, and other crafty materials, the domestic environment is delightfully detailed, from the family photographs hanging on the living room walls to the pork chops grandma is frying up in the kitchen.

By drawing on her childhood memories, Giordano has created a deeply personal and instantly accessible work that calls out for exploration.

Jason Peters, Extrospection. Courtesy of the artist.

9. Jason Peters, Extrospection, curated by Che Morales

A darkened room and well-placed mirrors make it difficult to gauge just how big Jason Peters’s glowing, snakelike sculpture Extrospection is. Viewing it and walking around it is a disorienting experience, as it appears to hang in an endless void.

Undulating and intertwining, the piece seems like some computer animation has come to life and frozen in place. The reality is more pedestrian than you might expect: Peters created this stunning artwork by chaining together humble buckets.