Galleries

Lynsey Addario, Known for her Searing Images of Conflict, Is the First Photojournalist to Join Lyles and King

The artist has covered war and humanitarian crises in the Middle East and around the world.

The artist has covered war and humanitarian crises in the Middle East and around the world.

Sarah Cascone

Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Lynsey Addario, known for her work covering conflicts and humanitarian crises in the Middle East and around the world, is joining New York gallery Lyles and King.

She will be the first traditional photographer on the gallery’s roster (although a few artists it represents do incorporate photography as an element of their practices in some shape or form).

“I liked the idea of joining a gallery that’s not specifically catering to photographers and photojournalists because I like to go beyond those borders,” Addario told Artnet News. “My goal is to be able to get the work out to a broader audience to people through museums and art fairs.”

For gallery founder Isaac Lyles, who works with a mix of emerging artists and older, under-recognized figures, Addario is a compelling, if unconventional fit for his stable.

Lynsey Addario, Veiled Rebellion. Two women on side of road, from Weha village, four hours in car to clinic. The father has lost two wives already, and has taken a third wife, half his age. His name is Shir Mohammad, and his wife, in burqua on hill, is Noor Nisa, 20. It is her first pregnancy, and her water has just broken and their car broke down on the side of the road. Shir Mohammad went to look for other transport, and Noor Nisa and her mother, Nazer Begam, 40, are waiting transport to the hospital. Photo courtesy of the artist and Lyles and King, New York.

“Many of the artists in our gallery programs address issues of identity, history, patriarchy, imperialism, global warming, and trauma,” he told Artnet News. “In Lynsey’s work, we have the raw, unvarnished, direct experience of an event of the happening of someone’s life. These photographs—taken in the moment, in the field, without sublimation—bear witness to those issues, often with profound empathy for her subject.”

“In my experience, the pictures and the stories that get seen are the ones that have really compelling, some would say beautiful photographs, which obviously is controversial because I’m often photographing very devastating scenes,” Addario said. “My first responsibility is, of course, getting the facts and making photographs that tell the story accurately. But I’m trying to find a way to photograph something that will engage the reader, rather than making them turn away.”

Lynsey Addario, Soldiers with the 173rd battle company, on a battalion-wide mission in the Korengal Valley on the Abascar Rideline, looking for caves and weapons caches and known Taliban leaders. Specialist Carl Vandeberge, center, and Sargeant Kevin Rice, behind, are assisted as they walk to a medevac helicopter minutes after they were both shot in the stomach during a Taliban ambush, which killed one soldier, and wounded both of them. Vandeberge and Rice were flown out immediately for surgery (2007). Photo courtesy of the artist and Lyles and King, New York.

Addario became a war photographer after the September 11 attacks in 2001, and has worked in countries including Iraq, Darfur, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The job has put her in unimaginable danger, such as being kidnapped not once, but twice, including a harrowing week-long ordeal in Libya in 2011, recounted in Addario’s 2015 memoir, It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War. (The book is being adapted into a limited television series with Paramount and Viacom, and Addario is also the subject of a forthcoming documentary feature film.)

Lynsey Addario, Soldiers with the Sudanese Liberation Army sit by their truck while struck in the mud in Darfur, Sudan, August 21, 2004. The SlA is one of the Sudanese rebel groups controlling parts of Darfur. Rebels are currently staging a 24-hour boycott of the Nigerian peace talks for Sudan in protest of recent new attacks against civilians in Darfur, which they say killed 75 civilians in six villages (2004). Photo courtesy of the artist and Lyles and King, New York.

Most recently, Addario has been on the ground in Ukraine, documenting the Russian invasion and its deadly effects. Her photo of a Ukrainian family hit by a mortar attack, a mother and two children lying dead as soldiers attempt to save the father, was a finalist for this year’s Pulitzer Prize. Addario was just steps away from the falling shells that killed them.

“The unpredictability of Ukraine is what makes it really scary,” Addario said. “It’s an artillery war. You never really feel safe, but you feel like you’re in a situation that is a little back from the front line, and then a missile lands next to you.”

Lynsey Addario, Ukrainian soldiers attempting to aid a family moments after they were hit by a mortar round while fleeing the suburb of Irpin, seeking safety in Kyiv. Tetiana Perenyibis and her children Mykita and Alisa were killed. Anatoly Berezhnyi, a church volunteer who was helping to usher the family to safety, was also killed in the strike. A steady stream of Ukrainian civilians made their way over a footpath beside the blown-up Irpin Bridge to try to escape fighting in the suburbs to the northwest of Kyiv as the Russian army advanced toward the capital. Mortars fired from Russian positions targeted the area of the bridge (2022). Photo by Lynsey Addario for the New York Times, courtesy of the artist and Lyles and King, New York.

Some of the photographer’s images have become widely reproduced, such as her striking photograph of a pregnant women and her mother, dressed in vibrant blue robes, as they wait in the Afghanistan desert for a ride to the hospital after their car broke down.

“With photos of this caliber, telling stories of this urgency, it would just be wrong not to show them,” Lyles added. “Sometimes, you have to take risks and say ‘this is urgent work, the market should come to this.’”

Lynsey Addario, Ukrainian families live below ground in a subway station, where many of them have been for about one week as Russian forces fight Ukrainian forces on the outskirts of Kyiv, Ukraine, March 2, 2022. The capital city of Kyiv is extremely tense as Ukrainian men and women prepare for battle as Russian troops have entered Kyiv (2022). Photo courtesy of the artist and Lyles and King, New York.

This will be the first time working with a dealer for Addario, who previously handled all her own sales, working with Epilogue, a Los Angeles post-production house recommended by director and photographer Sam Taylor Johnson, to produce prints.

Collectors typically reach out to Addario after seeing her work in the New York Times or National Geographic. But as a mother of 11- and four-year-old children with a busy travel schedule that has her on the road as many as seven months a year (when we spoke, Addario was on her way to the airport for a shoot with National Geographic in the Amazon), doing it on her own was becoming increasingly challenging.

Lynsey Addario, The forest burns around the Butte Lake Compound during the Dixie fire, August 27, 2021. The fire started in July 13th, and by October 2021, it had burned 965,000 acres (2021). Photo courtesy of the artist and Lyles and King, New York.

Then, a relative of her husband suggested meeting with Lyles, who has run his namesake gallery on the Lower East Side since 2015. Addario, who was working at the time on her 2022 retrospective exhibition at New York’s School of Visual Arts, invited him to see the show.

Lyles was already a fan, having been introduced to Addario’s work by the writer, artist, and curator Danny Moynihan, currently the director-at-large at Nino Mier, the Los Angeles gallery with locations in New York, Brussels, and Marfa, Texas. Upon meeting in person, Lyles and Addario began hammering out an arrangement to work together, starting with a solo show at the gallery next spring, organized with Moynihan.

Lynsey Addario, Khalid, seven years old, sits outside of the medical tent of a U.S. military base after elders from a village claimed he was injured by shrapnel from a bomb dropped by American troops near his home. American forces admit to dropping a bomb in the area, and say the boy was most likely injured in the attack, but can not confirm 100 percent. Civilians throughout Afghanistan have been victims of both Taliban attacks and United States bombs (2007). Photo courtesy of the artist and Lyles and King, New York.

Addario comes to the gallery with a built-in collector base that includes British rock star Elton John—and during the SVA show, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stopped by for a private tour of the exhibition.

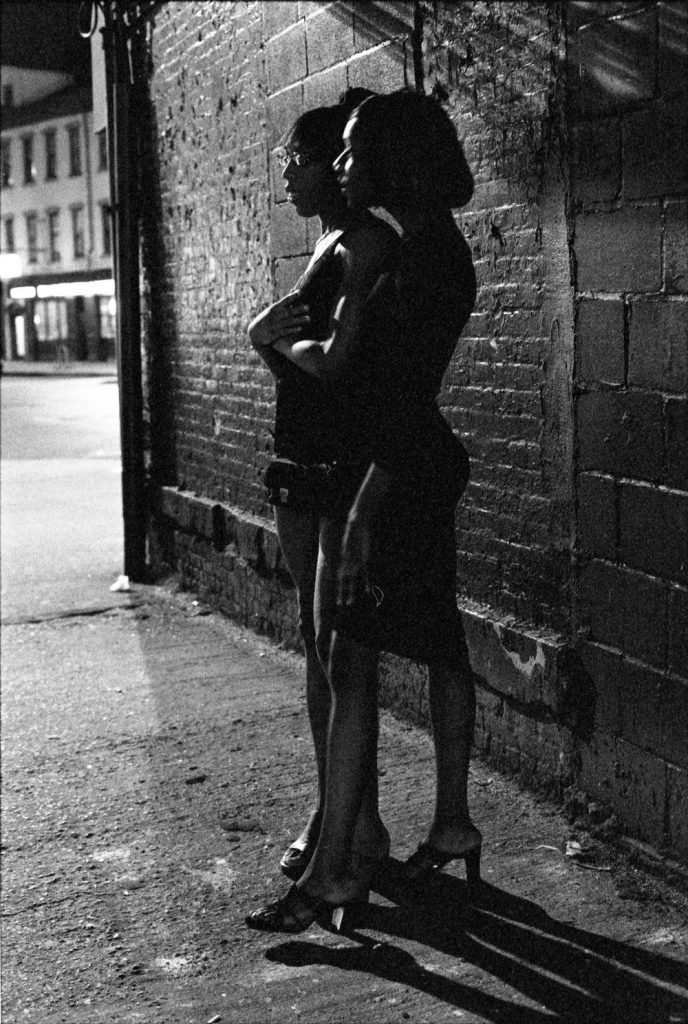

More importantly, with a career spanning 25 years, Addario boasts an impressive range of work, from California wildfires to African famines to survivors of sexual violence. Aside from last year’s retrospective, some of the photos haven’t ever been shown, such as shots of trans sex workers from 1999, a selection of which go on view today in “A District Defined: Streets, Sex, and Survival” at 401, a new space in New York’s Meatpacking District.

Lynsey Addario, Trans sex workers wait for clients in the meatpacking district in New York (1999). Photo courtesy of the artist and Lyles and King, New York.

Both the artist and dealer are eager to delve into the archives and to present these works to the art world.

“What’s exciting to me is that Isaac is coming to my work with a super fresh eye—not from the genre of photojournalism,” Addario said.

“In a world where most of the work of a photojournalist is experienced on an iPhone, a laptop, or briefly on the newspaper page,” Lyles added, “this is an opportunity to slow down, to pay closer attention to the issues at play and the subjects in the work, giving them greater dignity.”