What I Buy and Why

Advisor and Curator Sigrid Kirk on Her Commitment to Women Artists and the Marlene Dumas That Got Away

The collector took solace in a vulnerable Gillian Wearing self-portrait during lockdown.

The collector took solace in a vulnerable Gillian Wearing self-portrait during lockdown.

Lee Carter

New Zealand-born, London-based collector Sigrid Kirk wears many hats. First, there is her eponymous art advisory, where she serves as cultural strategist and independent curator. Then there are the scores of institutions she’s involved with, including the Drawing Room, where she is a trustee, as well as the fairs Eye of the Collector and Glasgow International in the role of advisory board member.

In addition, each year Kirk and her husband collaborate with Te Tuhi gallery in Auckland to help fund an artist residency at Yorkshire Sculpture Park for Maori and Pacific Island artists. The couple are also patrons of Dundee Contemporary Arts and Fruitmarket Gallery in Scotland, as well as the London art spaces Gasworks, Studio Voltaire, Iniva, and Goldsmiths CCA.

On the curatorial front, Kirk recently selected the artworks for display in the tony members club Maison Estelle in Mayfair, as well as its sister club in the country, Estelle Manor. Before that, she curated the public art exhibition “Breath Is Invisible” to address issues of social inequality and injustice.

To top it off, Kirk helped organize Build Your Own Art World, the inaugural conference from the Association of Women in the Arts (AWITA), of which she’s a cofounder. The conference, hosted last week by Phillips London, brought together inspirational women working at a range of art organizations, from Frieze to Tate Britain, all dedicated to supporting the professional development of women in the visual arts.

All the while, Kirk has built a deeply personal collection of art. Recent acquisitions include works by Jesse Darling, Penny Goring, Misheck Masamvu, Grace Ndiritu, Sola Olulode, and Jane and Louise Wilson, from whom she purchased a video from their 2022 exhibition “The Toxic Camera” at Maureen Paley gallery.

We chatted with Sigrid Kirk about the many hats she has donned and how they have informed her collection.

What was your first purchase?

I arrived in London from New Zealand in 1997 after completing a master’s degree in the history of art. One of the first shows I saw was a Cathy de Monchaux exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery. Her intricately constructed sculptures use materials such as glass, paper, metal, fur, and leather, and they juxtapose and evoke conflicting experiences of soft and hard, seductive sexuality and restraint, all of which fascinated me. I think I had been reading Linda Nochlin and feminist theory at the time. My first job was working at an art shipping company and at an art fair I met Cathy’s then dealer and found out she had made a small edition; a leather box inlaid with red velvet that suggested folded vulvas, within which nestled two cast-metal frogs with enlarged sexual organs. Each frog is attached to a chain and both are tied together to a nail. I’ve never hung them on the wall, preferring them to lie together. I could just afford the work, and he let me pay it off in installments.

Ro Robertson, Torso (2021–22). Courtesy of Sigrid Kirk.

What was your most recent purchase?

A large sculpture by Ro Robertson from Maximillian William Gallery, which was included in the recent show “Trickster Figures” at Milton Keynes Gallery. Robertson works site-specifically, often outdoors, with a focus on the queer body in the landscape—reclaiming the LGBTQ+ identity from being deemed ‘against nature.’ Made of Cor-Ten steel and marine paint, these materials bridge the artist’s family heritage of shipbuilding.

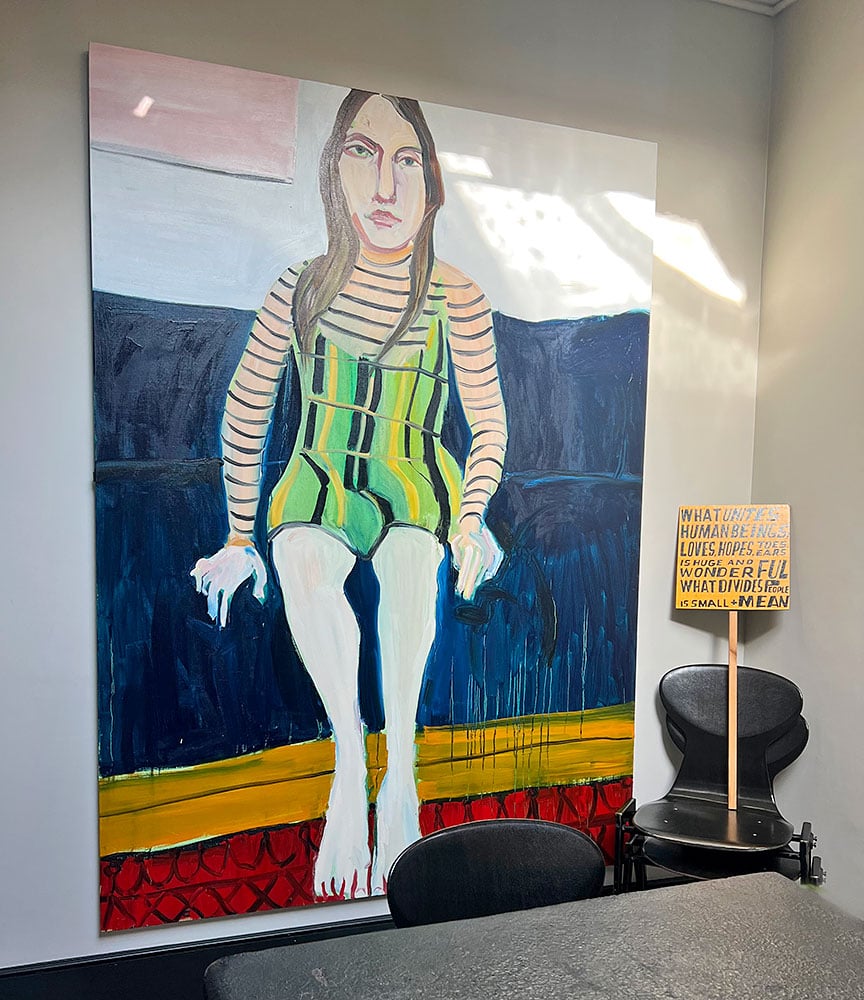

Sigrid Kirk with Gillian Wearing’s Untitled (lockdown portrait) (2020). Courtesy of Sigrid Kirk.

Tell us about a favorite work in your collection.

We have three works by Gillian Wearing, which are favorites. The maquette for A Real Birmingham Family (a public work commissioned by Ikon Gallery) stands on our kitchen table. I am worried about the fragmentation of society and inequality, but I do also feel quite positive about the future. For this work, Gillian sent out an open invitation to the people of Birmingham to apply to be cast as a life-size sculpture that would represent a modern family in the city. She had nearly 400 applications—people from all walks of life, from recent arrivals to people who felt very rooted in Birmingham. The family that was selected was two sisters, both single mothers with mixed-race backgrounds, who lived together with their children. It’s a very strong image of what the modern family can be in Britain.

We have also recently bought a self-portrait by Wearing, painted during the quiet and loneliness of lockdown, where she has literally and figuratively unpeeled the mask—she has long been fascinated with masks, if you recall her show at the National Portrait Gallery with Claude Cahun. This work, which was included in the recent Guggenheim retrospective, exposes the fragility and desperation of isolation. During lockdown I looked daily at Wearing’s photograph My Grip on Life is Rather Loose!, from the series “Signs that Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say” from 1992–93. Where once it seemed humorous, at that moment in time it felt too close to the bone.

Left: Gaia Fugazza, Blue Tits (2020), and a sculpture by David Batchelor. Courtesy of Sigrid Kirk.

Which works or artists are you hoping to add to your collection this year?

I would love to purchase a piece by Otobong Nkanga or Kapwani Kiyanga, as well as younger artists including Rene Matić and Tanoa Sasraku. I’m also watching the painter Vanessa Raw. I would like to have another smaller Chantal Joffe and a Kaye Donachie, both of whom explore the intimate act of painting and portraiture.

What is the most valuable work of art that you own?

I struggle with the of idea of value, particularly in relation to art made by women, because while there is certainly more visibility for women artists and women as cultural leaders across the art ecology, visibility is only one half of the equation. There is still a bit of a lag when it comes to value across the market as a whole. For me the value equation needs to focus more on the magic of art to heal, convene communities together, to provoke thought, and express the inexpressible.

Sigrid Kirk with Everlyn Nicodemus’s L’obstinée (The obstinate) (1987) above the fireplace and Laura Gannon’s Mysterious For (2016) on the wall. Courtesy of Sigrid Kirk.

I recently bought a wonderful work painted in the 1980s by the “clandestine” artist, writer, and curator Everlyn Nicodemus—who, at 70, is finally getting her due. She’s an extraordinary artist and person, one of the strongest feminist voices to emerge from Eastern Africa in the past 30 years. Her powerful works center on personal and cultural trauma, as well as the role art can play in healing. Her Självporträtt (Self-Portrait) was purchased in 2022 by the National Portrait Gallery in London, and is the first painted self-portrait by a Black female artist in the gallery’s collection. To me that is valuable.

Where do you buy art most frequently?

I tend to buy from a small number of galleries with whom I have relationship and share a similar aesthetic, but also like to find artists I don’t know at biennials or at the smaller nonprofit organizations like the Drawing Room, Studio Voltaire, Chisenhale, Gasworks, and Spike Island—they are the engines of the art world.

Chantal Joffe, Esmé on the Blue Sofa II (2018). Courtesy of Sigrid Kirk.

Is there a work you regret purchasing?

I don’t have time for regrets. My collection is fairly eclectic and is more of a documentation of my journey in the art world than about specialization. This stems from my time at the experimental Zoo Art Fair, a London-based nonprofit art fair originally held in the London Zoo in Regent’s Park, and showcasing new and innovative contemporary artists.

What work do you have hanging above your sofa? What about in your bathroom?

Hanging above my sofa is an installation of paintings by Alex da Corte that are reverse-painted in his neo-Pop expressionistic style. These headshots show how consumerism strips identity bare and renders it strangely plastic. In my bathroom I have a pair of ceramic knickers on the floor by Lindsey Mendick, and a ceramic wall sculpture by Paloma Proudfoot of latticed hands. Although the artists have collaborated as the collective Proudick and been described as a pair of “dangerous broads,” I bought the works separately. I like the bold imagery and storytelling they employ, often exploring personal histories. For me these two works displayed together conjure up the tropes of the Alfred Hitchcock shower scene, but in a witty and defiant subversion of that male gaze.

What work do you wish you had bought when you had the chance?

I could almost have bought a Marlene Dumas watercolor in the 1990s, but I would have had to choose between those and a roof over my head. I wish I had chosen the Dumas. Recently I was annoyed I didn’t have the budget for a great painting by Alvaro Barrington, who I think is bloody brilliant as a person and an artist. He is so good, he can get away with anything because he has a vision and a plan. I wish I had a collecting plan, but I tend to make it up as I go along.

If you could steal one work of art without getting caught, what would it be?

I would engineer an audacious heist and steal all 14 of Francisco de Goya’s “Black Paintings” from the Prado museum and install them in a minimalist, purpose-built space on the coast. There I would just sit during the day and consider the bleakness of humanity, fold my own growing insanity up into a neat and tidy pile, then get up and go back to trying to do something about it in my own little way. Obviously, a psychotherapist would have a field day with this.