A close-up painting of the back of a woman’s head, hair parted straight down the middle. A simplified, cartoonish portrait with saturated colors. An elongated, not-quite-human form against a neon gradient background.

You might think we’re describing paintings by some of the hottest young artists in the market right now: say, Julie Curtiss, Nicolas Party, and Emily Mae Smith. But these descriptors could just as easily be applied to the work of the Chicago Imagists (Christina Ramberg, Jim Nutt, and Ed Paschke, respectively).

The wildly inventive group got its start in the 1960s out of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and became known for their unconventional mash-ups of bold, graphic figures and eye-popping, day-glo palettes. While the aesthetic was divisive at the time, the group has received a notable uptick in attention in recent years. Their prices still lag far behind their young successors, whose work can soar into the seven figures at auction.

“The work is currently of great interest to a variety of younger artists, and it has been for a long time,” said Chicago dealer John Corbett, whose gallery, Corbett vs. Dempsey, has long championed Chicago Imagist painting. “But there is a resurgence of that interest and that’s often a place where interest from curators and collectors starts.”

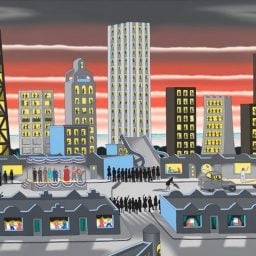

Phillips is showcasing work by more than two dozen artists in the selling exhibition “Cooler by the Lake: Chicago Art 1965–1985” (through February 5). Paintings by Jim Nutt are the most expensive of the group, with asking prices of up to $2.5 million for a 1970 painting. Many of the other works range from five to six figures, such as a Gladys Nilsson watercolor for $25,000 and a major 1969 painting by Karl Wirsum for $450,000.

“The enthusiasm we’ve seen for these artists extends well beyond Chicago to collectors around the globe,” said Miety Heiden, head of private sales at Phillips. “Their works resonate with such a wide pool of collectors.”

Celebrated or Shunned?

Karen Lennox, a former director of Chicago’s Phyllis Kind Gallery and the curator of the Phillips show, says that the Imagists “have had many appellations attached to them—goofy, shocking, irreverent—yet, historically, one can trace their predecessors back to the Italians and the Dutch masters as easily as Marvel comic books.”

Recent exhibitions include last year’s “Private Eye: The Imagist Impulse in Chicago Art” at Newfields in Indianapolis and, back in 2018, “Hairy Who? 1966–69” at the Art Institute of Chicago. That show took an in-depth look at the group’s six original members: Jim Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum.

Along with Ed Paschke, these remain some of the most famous names associated with the movement. In early 2020, Nilsson had a two-gallery, five-decade retrospective at the Chelsea spaces of Matthew Marks and Garth Greenan.

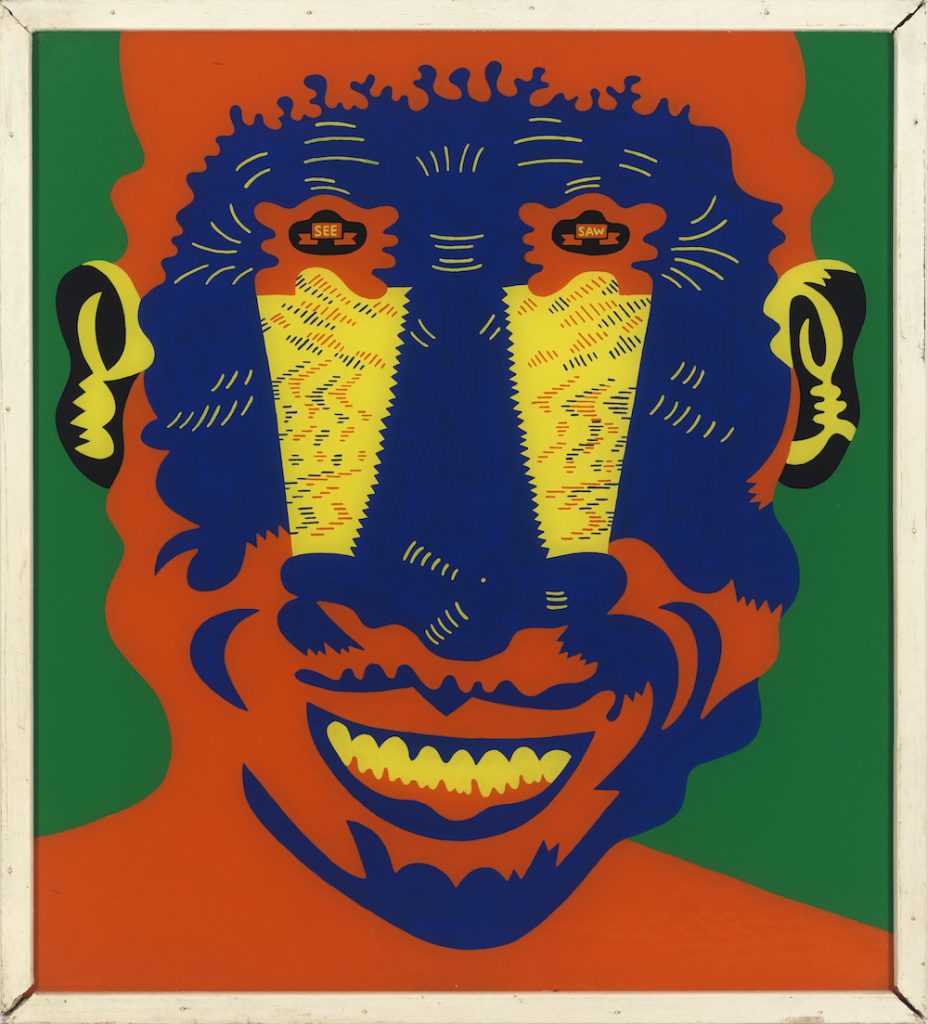

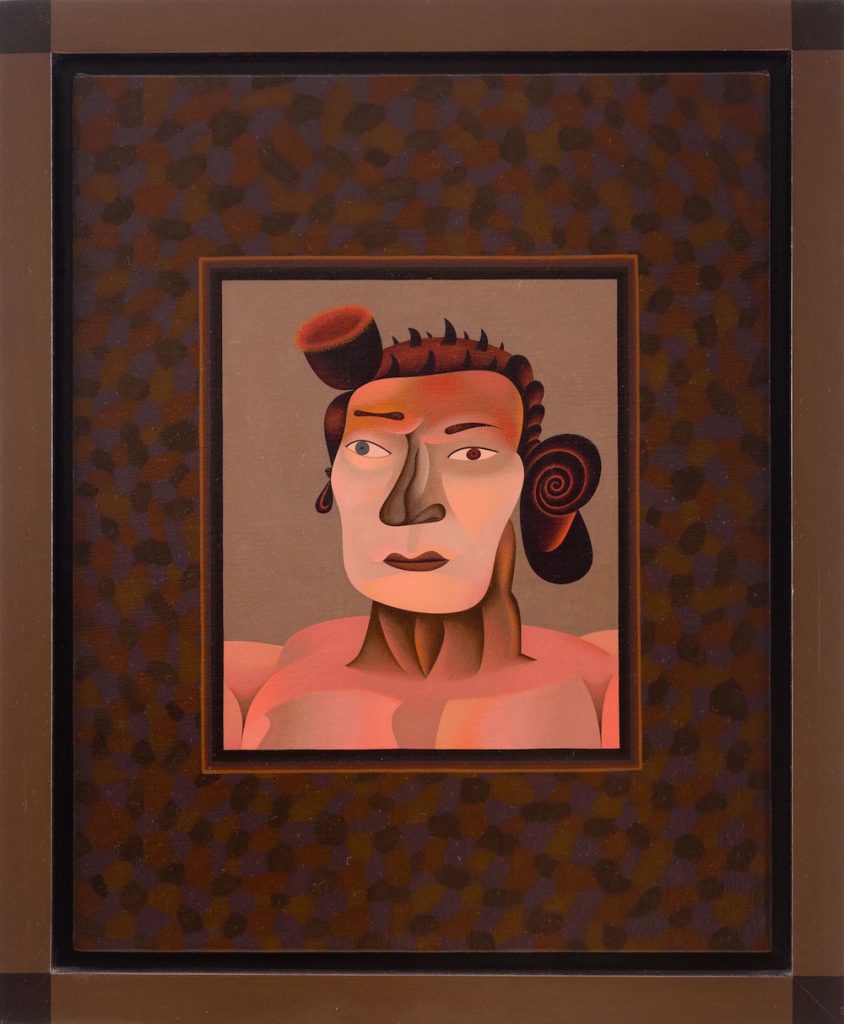

Karl Wirsum, Portrait of Al Blum (See Saw) (circa 1967). Image courtesy the estate of Karl Wirsum, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago and Derek Eller Gallery, New York.

The Imagists have always been prized by a core group of supporters in the midwest. But some feel they were unfairly ostracized by tastemakers and critics on the coasts.

“I think it depends how you look at it,” Corbett said. “In its era, let’s say in the ’70s, within Chicago there was in certain camps a perspective that their position was hegemonic and that they were unfairly dominating the scene. That’s specific to Chicago.”

Even outside the city, however, the Imagists were making waves. During the ’70s, Nilsson had a solo show at the Whitney; Nutt appeared in the Venice Biennale and at shows at SFMOMA, the Walker, and the Rijksmuseum; most of the Imagists were included in the Whitney Biennial at one point or another. There were group shows in South America and England.

Curators like Tom Armstrong and Jim Demetrion helped the work to find its way into major museums including MoMA, the Hirshhorn, and MUMOK Vienna. Former MoMA curator Rob Storr “was and is a great champion,” Lennox noted.

In the decades that followed, however, the work fell out of fashion, and then, for a time, out of view.

Stephen Fleischman, the former director of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art (MMCA) in Wisconsin, which has one of the best Imagist collections, said he wasn’t exposed to the Imagists’ work growing up on the East Coast. Part of this, he suggests, was due to provincial bias. “I knew how—I’ll just say it, ‘snooty’—the East can be,” he said.

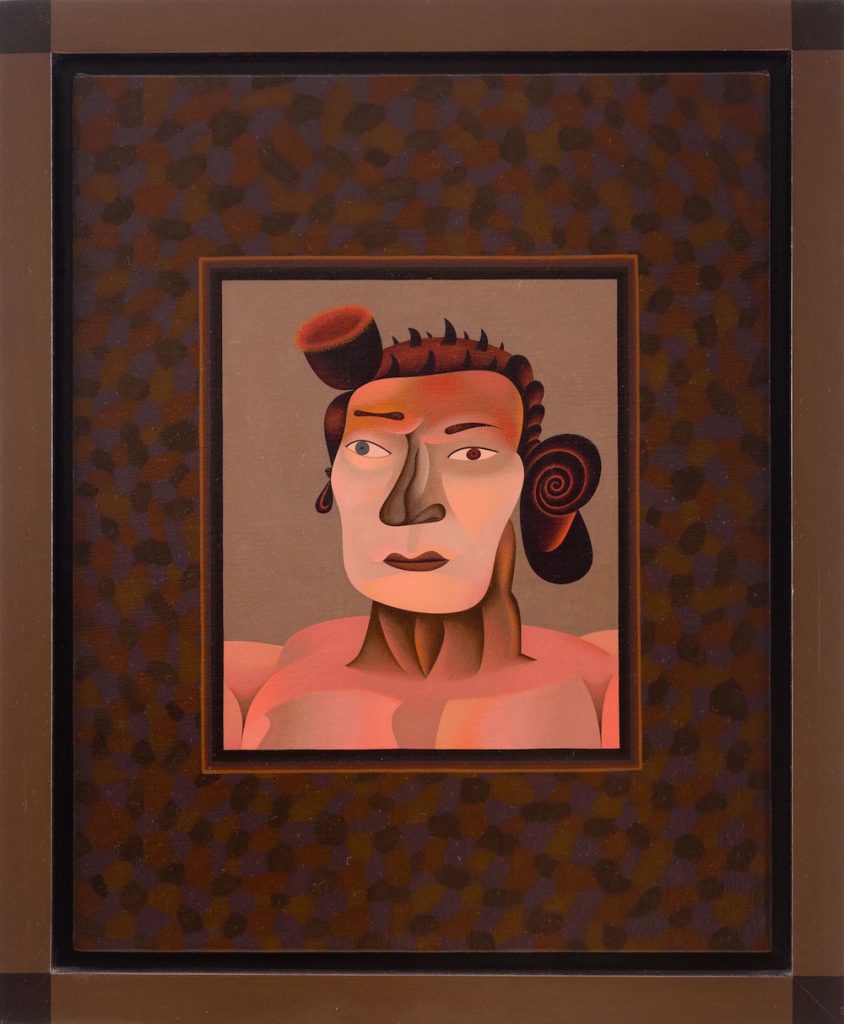

Jim Nutt, Trowel. Image courtesy Phillips.

Some collectors of Imagist work in Chicago also felt unappreciated locally, as major Chicago museums had their eyes on art with a more international profile. “I was fortunate enough to meet some [Imagist] collectors who didn’t really feel that they got the full attention of the Chicago museums,” Fleischman said. That helped him build a collection of more than 300 works by Imagists and their cohorts. “Over the last 10 years, it has been a sort of drumbeat slowly building,” he said.

In recent years, the museum has loaned works to institutions in Europe as well as roughly half a dozen to the 2018 show at the Art Institute. Simultaneously, collector interest has been broadening. About three years ago, calls for Imagist works started coming in from as far afield as France, Greece, Chile, and Hong Kong, Lennox said.

A Market Disconnect

The Imagists’ illustrious history and enduring influence aren’t always reflected in their prices—especially at auction.

The auction record for a work by Jim Nutt, the first Imagist to gain international acclaim, is just $516,500 for Plume (1989), sold at Chicago auction house Hindman in September 2019.

The Artnet Price Database lists 83 lots by Nutt offered at auction, with 11 selling for above $100,000. (The lowest price listed is $316, for a pen-and-ink drawing sold at Swann in 1995.) Privately, sources say the artist’s top works can fetch prices well into the seven figures, as evidenced in the current Phillips show.

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

“Private secondary market are where the early, rare masterpieces become available,” Lennox said. She noted that only Art Green, Nilsson, and Nutt are “living, working artists with a healthy primary market.” Green and Nilsson are represented by Garth Greenan; Nutt’s work is handled by David Nolan.

The rest are now only available on the secondary market, and many estates still lack gallery representation or have little material to speak of. (There are exceptions: Roger Brown’s estate is represented by Kavi Gupta, and the late Karl Wirsum shows with Derek Eller.)

“I don’t think that auction records are currently an accurate depiction of what actual value or significance is,” Corbett said. As is often the case at auction, “you’re not seeing what people want so much as you’re seeing what’s available.”

Among the most sought-after works by collectors are Nutt’s portraits and works on plexiglas and metal from the Hairy Who period; Paschke’s early paintings of women dressed in drag; Nilsson’s Hairy Who period watercolors and early reverse plexiglas paintings; and Winsum’s Hairy Who period paintings and wood puppets.

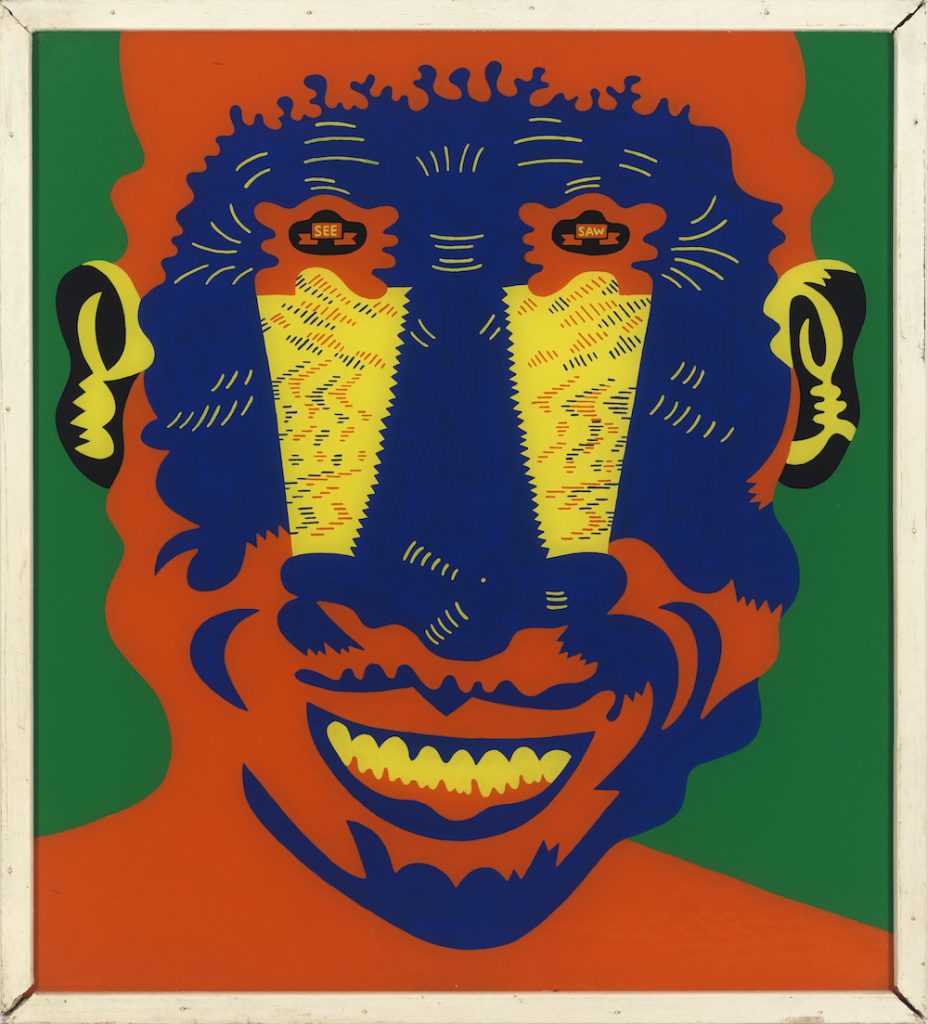

Christina Ramberg, Untitled (1968). Image courtesy the estate of Christina Ramberg, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, and David Nolan Gallery, New York

Notably, the Imagists had more female members than many other art movements that began in the ’60s. (Nilsson once noted that California, where she moved with her husband, Nutt, in 1969, had a far more gendered atmosphere than Chicago.)

Gender may be one reason some of the artists’ markets have stalled. Consider Christina Ramberg, one of the most revered of the Imagists, known for her paintings of hair textures and cropped images of women in extraordinarily detailed lingerie. She died in 1995 at the age of 49.

Lennox drew a comparison between Ramberg and the Italian artist Domenico Gnoli. “Both worked in the same time period, both died young, neither knew of the other yet the works speak volumes to each other,” she said. “Gnoli sells for $4 million. They are equals on every level except that Ramberg’s work is still priced far lower—hopefully not for much longer.”

Gnoli’s auction record stands at $11.7 million, set at Christie’s London in 2019; Ramberg’s is just $45,000, set in 2017 at Wright in Chicago in 2017. One of Ramberg’s works in the Phillips show, Untitled (Samuri Coat) (1982), is priced at $225,000.

Gladys Nilsson, Gigantica und der Messerschmitts (1965). Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

Sometimes, interest has come in fits and starts. Over the past 20 years, we’ve seen “little moments where it looked like something amazing was happening with one or another of the artists,” Corbett said. Jeff Koons, for example, organized an exhibition of Ed Paschke’s work at Gagosian in 2010.

“That seemed like a moment where all boats would rise with that tide—and that didn’t happen at all,” Corbett continued. “Gagosian did not continue to have a vested interest in Paschke. That was clearly something that was done for Koons.”

In the end, “what that ended up doing was something which happens with some frequency, which is that that it made the Paschke market very confusing.”

The current record for Paschke at auction is $245,000, paid for Bag Boots (1972) in 2014 at Christie’s New York. Like many of the other top Imagists, prices on the private market are higher.

For longtime fans, it is heartening to see these artists gain recognition, even if it’s modest and a half a century late. Fleischman fondly recalled Imagist artist Ray Yoshida handing out leis at the opening of a show of his work at MMOCA as a nod to his Hawaiian heritage. Yoshida’s estate later left the museum a plethora of his own work and that of his students. “It has been fun to watch the arc of their careers,” Fleischman said. “I’m glad that they’re finally getting their due.”