Art & Exhibitions

Why Is Jim Campbell’s Low-Res Video Art So Compelling, Even Captivating?

He's lighting up New York with a show of new works and a 30-year museum survey.

He's lighting up New York with a show of new works and a 30-year museum survey.

Benjamin Sutton

Jim Campbell wants to give your eyes a workout. Our seeing muscles have grown accustomed to sharp pictures that require little effort to decipher, so Campbell has spent three decades blurring, diffusing, and deconstructing images to the point that we really have to look, hard, in order to see them. A former engineer who spent 25 years making high-definition TV chips in Silicon Valley, Campbell has adapted to the age of high-definition videos by making his so low-definition that their images verge on abstraction. The best works in two concurrent shows in New York City—an exhibition of his new works at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery in Chelsea and “Rhythms of Perception,” a three-decade survey at the Museum of the Moving Image (MMI) in Queens—employ formal techniques from video art and sculpture to deliver deeply evocative images.

“The experiments I do I actually do for me, because I’m really interested in what will work well, and what won’t, and if they’re interesting enough I’ll present them to everyone else,” Campbell told artnet News. “The low resolution is kind of a universalizing technique.” Freed of specific details, his blurred and distorted videos become more expressive and evocative.

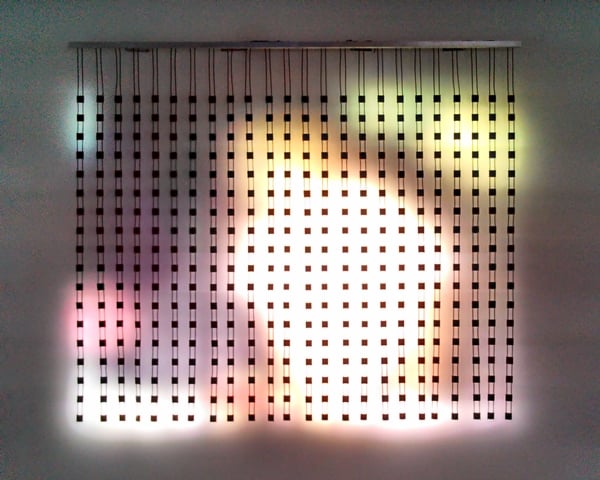

“Jim Campbell: New Work” at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery installation view.

Jim Campbell, courtesy Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York.

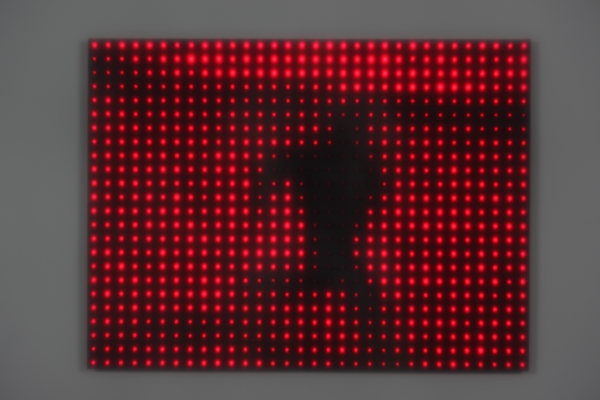

Campbell’s works display video footage—some shot by him, some bought off eBay—via various delivery systems. These include LEDs, LCDs, projectors, TVs, customized electrical displays, and video screens, often mounted behind diffusing Plexiglas or, in the newest works, machine-carved resin. The subject of the work is often the act of perception itself—our ability, for instance, to discern in Ambiguous Icon #1 Running Falling (2000) the silhouette of a person moving against a background of 165 red LEDs.

In Home Movies, Pause (2014), it doesn’t take long for the blurred forms and bright colors emanating from within 24 custom strips of LEDs to resolve as archetypal childhood imagery, such as videos of birthday parties, summer trips to the lake, and other staples of idealized American youth. At a time when we are constantly assaulted with crisp, legible images, Campbell’s seemingly futuristic works present us with the (retro) challenge of trying to make sense of blurry videos.

“Most of my work you understand because it’s moving, so when it stops, it becomes this relatively abstract image,” he said. “On the other hand, you’ve just seen it move, so even though it’s abstract, you know what it was.”

Jim Campbell, Ambiguous Icon #1 Running Falling (2000). Loan courtesy of Jim Campbell, Naomie & Charles Kremer.

Photo: by Sarah Christianson.

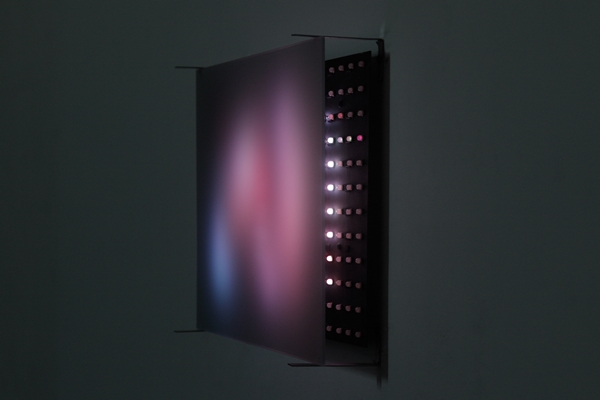

In many of Campbell’s works, video serves simultaneously as content and a formal element. The fragments and suggestions of images register both as footage—of clouds, birds, crowds, waves, etc.—and as non-figurative light patterns. At the MMI, there are flickering crowds at Grand Central Station playing across a “screen” of suspended ribbons dotted with LED bulbs in Exploded View Commuters (2011), which become completely abstracted when not viewed from straight-on. Or, at Bryce Wolkowitz, in Topography Reconstruction Wave (2014), the footage of a crashing wave plays behind a thick layer of resin sculpted to represent a photograph of a wave. This work, part of a new series employing more sculptural elements than much of Campbell’s preceding works, culminates when the blurred video of the wave seems to line up perfectly with the sculpted resin wave encasing it.

Another work in the resin series, Self Portrait in Positive Light (2014), is just a few weeks old and the newest piece at the MMI. It features a screen of more than 1,000 LEDs playing a looping video of a flame behind a resin rendering of a photograph of Campbell’s face. In addition to the process of stripping away visual information in his low-resolution videos, he is increasingly interested in the conversion of one type of media into another—in the case of the resin works, transforming black-and-white images into three-dimensional sculptures. The effect is deeply unsettling because of the way in which the video’s flickering lights interact with the translucent resin.

Jim Campbell, Topography Reconstruction Wave (2014).

Jim Campbell, courtesy Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York.

“As the lights change it distorts based on how thick the resin is, and what that does is that as the light passes through the face it feels like the face is moving, which goes back to this theory about some of the very earliest cave paintings that we have found; some people have suggested that with fire in there that they were actually animated,” Campbell explained. “And this work, using much newer technology, exaggerates that notion of using the flame to create movement, to make it feel as though the object is moving. It’s creepy. I was glad that I included it at the last minute because my work tends to not be creepy; if it’s on the edge it’s about perception, so it was nice to do something different. I didn’t do it for that reason, I didn’t know it would be creepy, I just wanted to do a portrait.”

Uncharacteristic though it may be, Campbell’s self-portrait harks back to the earliest work on view at the MMI, 1985’s experimental documentary Letter to a Suicide. The 30-minute film features footage of Campbell and his parents addressing the artist’s brother, who had committed suicide about a year earlier after struggling with schizophrenia for years. Though Campbell’s work generally foregrounds formal and technical concerns over expressive content, Letter to a Suicide cuts right to the bone. Along with Last Day in the Beginning of March (2003)—a room-sized installation of 26 blinking spotlights that forms an expressionistic, memoir-like account of death and mourning—Letter demonstrates just how emotionally charged Campbell’s work can be. The creepy self-portrait and the Home Movies series incorporating the childhood video footage sourced from eBay mark a new reorientation toward expressive work.

Jim Campbell, Ambiguous Icon #2 Fight (2000, side view). Loan courtesy of Jim Campbell & D. Scott Olivet.

Photo: by Sarah Christianson.

For Steve Dietz, who curated the MMI exhibition, Letter to a Suicide—Campbell’s first and only film—is “an end point that becomes a beginning point,” as he put it during a recent talk at the museum. From that early experiment in moving image work, which melds elements of documentary and experimental film, Campbell has spent the last three decades experimenting with moving images as a kind of raw material. The new carved resin works are both a continuation of that trajectory and a major departure from it, adding, as they do, new figurative surface elements which distort the videos playing beneath the surface. Or, in Dietz’s words: “Jim in many ways is moving from representation into perception.”

“Jim Campbell: New Work” continues at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery through April 19. “Jim Campbell: Rhythms of Perception” continues at the Museum of the Moving Image through June 15.