Art Fairs

Will the Havana Biennial 2015 Be a Bonanza for Cuban Artists?

The biennial could easily be called Black Friday in the Tropics.

The biennial could easily be called Black Friday in the Tropics.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

In the coming days, bevies of dollar-toting collectors, curators, museum directors, and dealers will arrive on State Department-approved charter flights from Florida and descend onto the 12th Havana Biennial, which opens on May 22 and promises to be the art world’s version of Black Friday in the tropics. Among them are groups from the Met, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the Bronx Museum. But while these privileged masses take advantage of enhanced shopping opportunities—courtesy of improved relations between the U.S. and Cuba—other artists are calling for a boycott. Unfortunately, few people seem to be listening.

A convenient chill has settled over the art world. Despite the support of more than 2,500 prominent artists and intellectuals, countless acts of global solidarity, and thousands of words published across web and print media, support for Tania Bruguera, the artist who was arrested in December 2014 for her performance of Tatlin’s Whisper in Havana’s Revolution Square (see How Tania Bruguera’s Whisper Became the Performance Heard Round the World), has cooled precisely when her wardens, the Cuban government, are most vulnerable to criticism.

While a golden opportunity exists to denounce the regime’s ongoing detention of Bruguera, its appalling human rights record, and its arbitrary assault on intellectual freedoms, many normally outspoken critics of repressive regimes, like North Korea, Saudi Arabia, and Russia, have elected to remain strangely silent on the question of Bruguera and the upcoming biennial. One reason may be what one Cuban artist refers to as the anticipated “explosion of American collectors coming to buy.” As Ryszard Kapucinsky once penned, money changes rules into rubber bands. Another way to characterize similar topsy-turvy morals: When the going gets tough, the tough go shopping.

For those who still don’t know Bruguera and her trouble-making interventions, here is a recent description provided by the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) on account of the artist being this year’s recipient of the Herb Alpert Award in the visual arts:

“For Tania Bruguera art should be útil (useful). Always interested in creating performances in an environment that will transform ‘the audience’ into ‘active citizens,’ she works with the interplay between planned actions and spectators’ spontaneous reactions. The goal: actual—not symbolic—transformation. Her performances engage with issues of social responsibility, art ethics, power and control, political representation, and civil society.”

A celebrated international artist with few equals as a global gadfly, Bruguera has generated outsize attention for her Havana performance of December 29, 2014—an open-mike session consisting of a microphone and an invitation to enjoy “1 minute of censor-free speech.” In the words of Peruvian historian and curator Gustavo Buntix, Bruguera’s action sought “to grant a minute—sixty seconds—of freedom of expression” to average Cubans “who aspire to be citizens.” Though the very same artwork had been performed at the 2009 biennial, the Castro regime responded by arresting Bruguera and detaining her without charges (see Cuban Officials Brand Tania Bruguera a Criminal). The difference between 2009 and the eve of 2015? In a phrase, the normalization of relations between the U.S. and Cuba—which had been just announced by Presidents Raul Castro and Barack Obama.

In Cuba, as Bruguera’s situation amply demonstrates, raising provocative questions about the sorry state of civil liberties comes at a cost. Since her arrest and subsequent conditional release, the artist and her family have been surveiled, followed, harassed and, most recently, defamed in a now infamous government video that paints Bruguera not as a perpetrator of civil offenses, but as a full-fledged criminal, a “counter-revolutionary” in the pay of the CIA and right-wing Floridians. Not since 1971, when the poet Heberto Padilla was forced into publically confessing his ideological sins (along with his wife’s), has the Castro regime embarked on such a ruthless intellectual witch-hunt.

Despite advances in bilateral talks between the U.S. and Cuba, Bruguera’s case remains absurdly mired in last century’s Cold War politics. Late-night couch discussions weighing relative versus absolute freedoms and Che-era cultural antagonisms have, incredibly, resurfaced across panels, blogs, and Facebook pages the world over.

With the date for the opening of the biennial fast approaching, groups of art world veterans have split into pro- and anti-Bruguera camps. If their exchanges at times appear stuck in the same time warp as the ancient Cadillacs and Studebakers that cruise Havana’s streets, their opinions currently help shape the limits of Cuba’s political tolerance. One old-time argument that apparently still holds water is Fidel’s 1961 order to Marxist intellectuals: “Within the revolution, everything; outside, nothing.”

Naturally, some of Cuba’s most prominent artists are among those most sympathetic to the Castro regime. Beneficiaries of the largesse of international collectors—to whom many were first introduced during the wild shopping spree that was the 2000 Havana Biennial—they also rely regularly on the forbearance of the communist regime, which allows them to flash Cuban pesos while banking in dollars and euros.

Most prominent among these is Alexis Leyva Machado, alias “Kcho.” Hands down Cuba’s most successful artist, Kcho is Fidel’s favorite, as well as the recipient of numerous national honors. Recently, he accompanied Raul Castro to the Vatican to meet Pope Francis. While there, he presented the pontiff with one of his trademark boat paintings. It’s unclear whether he did so before or after Raul Castro declared that “his government does not comply with some human rights” [emphasis mine], to which Castro added, “But then again, who does?” (Note: Bruguera has reached out repeatedly to Kcho in his role as a Representative of Cuba’s National Assembly but has received no response to date.)

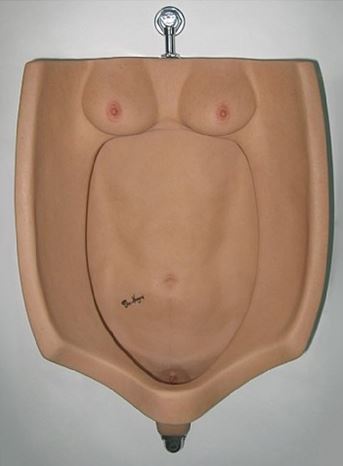

The-Merger, Lenguaje de Adultos, Homenaje a Marcel Duchamp (2013).

Photo: Courtesy artnet

If Bruguera’s name today is synonymous with censorship and intolerance in Cuba, Kcho and other figures like Rubén del Valle, the President of Cuba’s Fine Arts Council, and biennial director Jorge Fernández Torres have gradually revealed themselves to be emblematic of a type of opportunism not exhibited openly since the days of Stalin’s show trials. But this political and ethical expediency is, alas, not confined merely to artists and intellectuals living on the island. As is evident in the contributions of various prominent intellectuals to several public forums and multiple Facebook posts, not everyone has lined up with Bruguera following her illegal and arbitrary arrest.

A recent editorial debate hosted by the website of the Cisneros Collection proves a case and point. In it, five art world players—among them Buntix, writer Laurie Rojas, and artists Luis Camnitzer, Paul Ramirez Jonas, and Carmelita Tropicana—were invited to discuss the now fizzled topic of protesting the Cuban festival: “The Havana Biennial: To Engage or to Boycott?” The debate was a polite set-to centered on the idea—proposed by Buntix and Jonas, among others—that the biennial should be boycotted “as an act of protest.” Its premise was opposed vigorously by Caminitzer and parried daftly by Tropicana who likened the artist’s choice of venue—the public Plaza de la Revolución—to demonstrating on the Secret Service-protected White house lawn.

In an intervention titled “Ethical Dilemmas,” Camnitzer, an Uruguayan conceptualist—who is an erstwhile friend of Bruguera’s and a longtime supporter of the regime—contemptuously contrasted Bruguera’s “individual martyrdom” and the biennial, which he called “a collective political cause.” His principal premise is that threatening a boycott of the festival currently is both “fanatical” and “ridiculous.” Had Camnitzer—who has declared Bruguera to be “narcissistic” and “ego-ridden” in one Facebook discussion—acknowledged his vested interest in the 12th Havana Biennial, the conflicted nature of his views might have been clearer. The issue at stake is that Cuba’s official newspaper, Granma, announced only this last Tuesday that the Uruguayan artist will present a solo exhibition and a highly publicized workshop at Casa de las Americas, Cuba’s most prestigious cultural institution.

Consider, too, the multiple testimonials about Bruguera’s art and career on the website of the Herb Alpert Award. Among the contributors are critic and theoretician Boris Groys, Creative Time curator Nato Thompson, historian Andrea Giunta (who openly refers to the artist’s detention as well the international campaign to secure her freedom), and Bronx Museum director Holly Block. About Bruguera, Block writes: “Whether creating a performance in public space, working with recent immigrants, Bruguera has drawn worldwide attention provoking not only the viewer, religion, politics, as well as the Cuban government.”

While revealing of Bruguera and Block’s long working relationship, Block’s comments naturally omit mention of her present personal and professional quandary. While her friend and sometime collaborator languishes in a Kafkaesque legal limbo—harassed, lawyerless, and actively cut off from powerful friends and allies who might lend a hand—the museum director has engineered the first museum exchange between the U.S. and Cuba in more than fifty years. Titled “Wild Noise,” the exhibition, which serves as the first leg of the exchange, will open concurrently with the biennial at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.

When asked if she cared to elaborate on her thoughts about Bruguera, Block responded from Havana:

“I haven’t seen Tania in Cuba. For the “Wild Noise” exhibition we have focused on works from our permanent collection by U.S.-based artists, so Tania’s work is not included in the show. I strongly believe in cultural exchange, and believe that it is a vital tool for improving communication and dialogue. While we never planned to include Tania in this exhibition, I support her work and am saddened by her circumstances in Cuba.”

As Rojas writes on the Cisneros website: “There are a sufficient number of artists, curators, and collectors willing to turn the blind eye, and any authority above the [Biennial Organizing Committee] is going to be a direct party official who will have no qualms in defending their tactics in the name of “the revolution.” But if the biennial and other hardline cultural institutions within Cuba cannot be spurred onto change from within, surely something more than Twitter, Facebook and small-scale street protests can be done from without.”

Unfortunately, says Ramirez Jonas, the call for a boycott of the biennial went over like “a lead balloon.” While sharing via email that he found little traction among his peers for such an action, the New York-based artist acknowledged finding a residual amount of respect for the biennial and what he termed “a definitive ambivalence of showing solidarity for Tania while damaging the opportunities that people perceive the biennial will bring to Cuban artists.” A similar logic, in fact, has kept Bruguera and her closest supporters from calling for such an action.

In past conversations with this reporter, the artist has expressed extreme sensitivity to the idea that Cuban artists should be deprived of the opportunities this particular biennial will generate. It’s no secret that the last biennial to which American art tourists had legal access—the 7th Havana Biennial in 2000-2001—nourished an entire generation of artists that includes current art stars like Kcho, Carlos Garaicoa, Los Carpinteros, and Bruguera herself. “That was when artists became middle class in Cuba,” explained Bruguera in February. “After that, they started to travel, go to residencies, buy cars and homes.”

One indication of what such a windfall of art tourism might mean in 2015 is provided by The Independent. In an article on what it calls the coming American “invasion,” the paper reports a member of the Cuban collective called The-Merger predicting “a stampede” of collectors, art dealers, and museum directors for the biennial kick off. For proof he indicates a large pool table in the shape of the map of the Americas—the Bronx Museum has the work on reserve, he claims. The price? After bandying about previous six-figure Basel sales indicative of an overheated market, he coyly tells the U.K. paper simply: “A lot of money.”

“My goal is not to damage the biennial,” Bruguera has said. “My goal is to have my rights and those of others respected.” So while efforts at a boycott by Bruguera’s more rebellious adherents have proven ineffective, supporters say renewed efforts should be made to use the upcoming Havana Biennial to publicize her plight and that of other Cuban prisoners of conscience—among them the artist Danilo Maldonado, alias “El Sexto,” and dissident blogger Angel Santiesteban. Whatever happens, Bruguera’s fate will not turn on an independent and transparent judicial process, but it will certainly affect the state of free speech and artistic expression in Cuba for years to come.

According to curator and ex-Havana Biennial director Gerardo Mosquera, Bruguera’s case is a faithful mirror of the state of civil liberties and artistic freedom on the island. “The decision about Tania’s fate will not be taken by a prosecutor,” he recently told Chile’s La Tercera when asked what her ongoing detention means for art in Cuba. “If she’s jailed, it will happen after the biennial, when the international contingent has left, though it’s possible that she will be freed before, as if nothing had happened. Whatever happens, her case clearly serves as a warning to others.”