Artnet News Pro

Zero Bond Has Become the New York Art World’s Favorite Private Club. That Doesn’t Make It Cool

The club is an unholy marriage of kitsch aesthetics and the moneyed elite.

The club is an unholy marriage of kitsch aesthetics and the moneyed elite.

Annie Armstrong

About a year ago, when I first started reporting Artnet News’s gossip column, Wet Paint, I took it upon myself to try to get in to every art-world party I possibly could. I had a few methods of finding my way in. Typically, I emailed the proper PR (fairly easy), got someone to add me as a plus-one (a little tougher), or walked in confidently without an invite until someone noticed (pretty difficult). The parties I got dead-rejected from I’ll never forget; one of them was at Zero Bond.

At the very end of Bond Street (the address actually is 0 Bond Street), the members-only club sits sandwiched between an Equinox and the building that houses the Keith Haring Foundation. What happens inside is almost the perfect combination of those two things. Over two floors, Zero Bond encompasses meeting rooms, a Japanese omakase restaurant, a lending library of art books, a coffee shop, more meeting rooms, and a private dining space called the Baccarat Room. Inspired by the members-only clubs of London, it opened in 2020, and since then has garnered a reputation as a celebrity magnet. Its members pay annual membership rates ranging from $2,500 to $4,500 (plus some hefty initiation fees).

Becoming a member isn’t easy. “While we do not discriminate based on race, socioeconomic status, or profession, we are highly particular on character,” its website states. “We will only accept members that display a high level of integrity and demonstrate an ability to contribute to our Zero Bond community.” Many of those members are those in the fine art world, which suggests something about their socioeconomic status.

The interior of Zero Bond. Photo by Natalie Black.

“It’s like a local watering hole, which I know sounds, like, weird and tribal and animalistic,” art-collecting scion and Zero Bond’s curator, Sophia Cohen, daughter of Steve, said through a laugh. “A lot of great events have been thrown there. I threw a Richard Prince-themed birthday party on the fourth floor, which was really fun.”

I didn’t mention that I already knew it was a really fun party; I scene-spotted it from the street. Last September, a dealer at the Armory Fair tipped me off that Cohen would be hosting the event. That night, I threw on a dress and headed for SoHo to attempt my third and most difficult method of party entry. But no dice, I didn’t get in. So I spent the next 20 minutes lurking across the way, watching Max Levai, Bill Powers, Lily Mortimer, and other glitterati file in and out of the monolithic building in nurse and cowboy costumes, before deciding any further attempt to enter would be futile.

Fast forward a year, and I’m finally in. It was a Monday afternoon, and the energy on the fourth floor of the club was quiet, like a coworking space. Immediately upon exiting the elevator, my eye went directly to the Banksy Flower Thrower on the far wall of the club, divided into three mismatched frames. To my left was a truly hideous sculpture of an elephant in a suit, looming over me like a bouncer. (I don’t know who the artist is; Zero Bond’s press agent still hasn’t got back to me with an answer.)

An elephant sculpture of uncertain origins at Zero Bond.

To be fair, no party spot is going to be at its most exciting on a Monday afternoon in July, but the overall feeling of the joint was of a high-end hotel lobby, and I couldn’t imagine myself ever feeling casual enough within it to truly let my hair down. A lot of the curation felt a little silly: a Claes Oldenburg picture of a coffee mug and croissant hung without inspiration next to the coffee shop, and some Warhol prints of fish were, you guessed it, in the sushi restaurant. I started to think that maybe the Zero Bond that I had drawn up in my mind was far cooler than the real deal.

Some off-the-record research with people who spent some serious time inside all but confirmed this. One source told me that a private dinner in the Baccarat Room with some hugely wealthy members came with a cash-only bar. Another told me they spent all night at a Google executive’s birthday party waiting for Diplo to come, but he never did.

“I’d rather get drunk on the street,” that person added.

That doesn’t stop the VIP hordes (Kim Kardashian and Pete Davidson; gallerist Eli Klein; former Google CEO Eric Schmidt) from descending onto Bond Street. Most of that clientele is there because of one man: its proprietor, celebrity club owner and restaurateur Scott Sartiano.

The interior of Zero Bond. Photo by Natalie Black.

“Art is so integral to the downtown scene,” Sartiano told me while we sat in the club’s main lobby on a Marimekko couch. “So I always knew that had to be a part of Zero Bond.”

Sartiano, whose other clubs include Midtown hotspots 1 Oak and Up & Down, is meek and soft spoken, and as we talked, nearly everyone who passed by gave him a collegial “hello.” Wait staff instantly put down two glasses of water when we sat down, which neither of us touched.

At 47, he is is tabloid mainstay, known as a playboy who dated starlets like Anne Hathaway, Ashley Olsen, and Ashlee Simpson. So there was some surprise in May when his pal Eric Adams tapped him as the mayoral appointee to the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the country’s foremost cultural institution. “Perhaps,” one journalist wrote at the time, “Adams is looking for a fresh perspective on high art society from a nightlife luminary. Or perhaps he’s combining business with pleasure.” I think it’s probably the latter; I’ve already reported on Adams’s affinity for the high-flying nightlife the art world has to offer.

“I go to their meetings about once a month,” Sartiano said of his job at the Met, mainly as a proxy for Hizzoner. “It’s a big group, so they don’t necessarily ask me a lot of questions.” Indeed, from my conversations with Sartiano, who told me he was just now “getting his feet wet” in the art world, I have reason to believe he’s as much of a newcomer to the art scene as Adams is.

“I don’t remember who made this,” he said, gesturing to a sculptural lamp in the club’s restaurant. “But I know it was very expensive.”

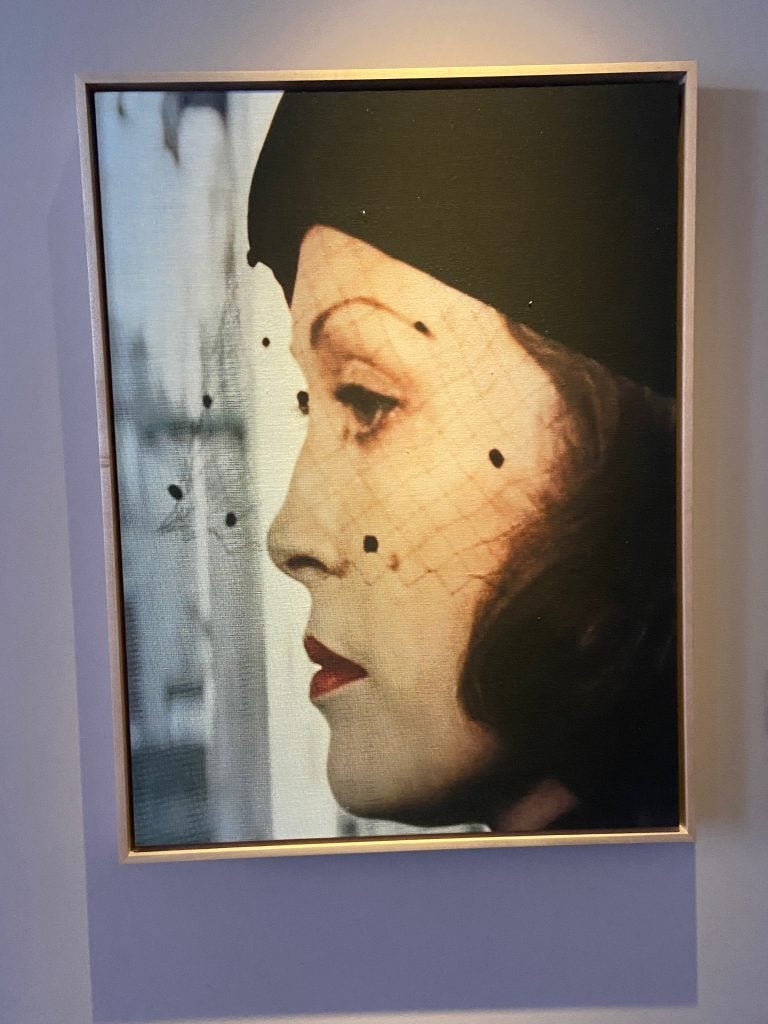

There are far more recognizable pieces scattered throughout the club: works by Andy Warhol (one of which was procured with help from former Warhol muse and art collector Jane Holzer), Petra Cortright, Lucien Smith, Francesco Clemente, and Robert Mapplethorpe. I also stopped in my tracks at a photograph by notorious art trader Stefan Simchowitz of a woman who appeared to be in mourning. It is titled Red Lipstick, Black Veil.

Red Lipstick, Black Veil by Stefan Simchowitz hangs proudly in one of Zero Bond’s bars. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some of these works are on loan from members, but most are a part of Zero Bond’s private collection, for which Sartiano partnered with Creative Arts Partners, which works for businesses like the Edition hotels, Facebook, and Zero Bond’s ostensible competitor, Soho House. After procuring several hundred works of art, he tapped Cohen to curate the walls.

“It was weird for me because I’m not really used to placing art in a member’s club,” Cohen told me over the phone. “It was an interesting project, because I tend to take a little bit more risk with my curation. I never thought I’d be working in a color scheme. But it actually was a fun way for me to, you know, challenge myself.”

The challenge is ongoing; according to Sartiano, members keep buying the works right off the walls.

“In this weird way, we’ve become a little bit of a gallery,” he said, saying that the artwork behind the check-in desk had just been switched out because a few different members bid on it.

The interior of Zero Bond. Photo by Natalie Black.

You may be wondering if Sartiano is following the same business model as real estate tycoon Aby Rosen, who is known for hanging saleable artworks as inventory at places like his Gramercy Park Hotel. Sartiano isn’t quite there yet, but his eyes lit up a bit when I said it had been done before.

In my mind, the landscape of art in New York City shifted in 2019, when the Met announced it would no longer be free to anyone who walked in off the street. The pervasive exclusivity of art spaces finally got to the last bastion of democratic art experience, and we’re all worse off for it. Neither Adams nor Sartiano had anything to do with the museum at that point, but their current involvement feels like a confirmation of my suspicion: art is no longer for the people, it’s for the moneyed few. The final kick in the side is that, having finally seen the inside of Zero Bond, it no longer strikes me as aspirational. By the time my tour of the establishment was through, I hadn’t even noticed that Sartiano had led me to the front door, and once again I was on the outside looking in. This time though, the allure had worn off.