Artnet News Pro

Who Won Auction Week? Here Are 12 Key Takeaways From New York’s Mind-Melting $2.3 Billion Fall Sales

From the priciest work to the top flop, here are our parting observations from two weeks of primetime New York auctions.

From the priciest work to the top flop, here are our parting observations from two weeks of primetime New York auctions.

Artnet News

This season, the Big Three auction houses came closer than ever to the excitement and panache of pre-pandemic auction madness, raking in more than $2.3 billion in sales spread out over two weeks, and returning to market heights not seen since the “Before” times. Among the successes, which included several broken records and white-glove sales, were a number of surprising twists and turns.

To help make sense of the ups, downs, and all-arounds, the Artnet News Pro team (Annie Armstrong, Katya Kazakina, Eileen Kinsella, and Tim Schneider) has returned to hand out its bi-annual auction awards.

Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

Sotheby’s hit well over $1 billion in a single week, the total was $1.15 billion for three nights of sales, even before you toss in the seemingly random addition of a rare copy of the U.S. Constitution that added another hefty and record by-far price of $43.2 million. The stunning total was fuelled by the unprecedented sale of the Macklowe Collection that accounted for $676.1 million of the total. The auction house also tapped into white-hot demand for ultra-contemporary works with a new sale category called “the Now,” which preceded the more traditional contemporary evening sale, and added a further over-estimate $71.8 million to the total.

Christie’s also organized a robust series of sales and realised $971.2 million for its 20th and 21st century art auctions including $332 million for the high-profile Cox collection, a single owner sale that sparked intense competition for rare Impressionist masterpieces. Phillips posted what it said was its highest ever total for an evening sale, taking in $139.1 million in an evening sale on November 17.

Mark Rothko, No. 7 (1951). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

It says a lot about the toppy market for Mark Rothko that the priciest lot of the week, $82.5 million paid for No. 7 (1951), offered as part of the Macklowe Collection, does not represent the most expensive Rothko ever sold at auction. That would be Orange, Red, Yellow (1961), which sold for $86.9 million at Christie’s New York in 2012. The Macklowe Rothko is now the second most expensive work by the artist sold at auction. On Monday November 16 at Sotheby’s, No. 7 came on the auction block with a third party bid, guaranteeing it would sell no matter what. It was estimated at $70 million to $90 million.

It was bought by a client of the chairman of Sotheby’s Asia. The eight-foot-tall canvas features horizontal bands of pink, yellow, and orange, and had never appeared at auction before. The second highest price of the week was $71.4 million paid at Christie’s for Vincent van Gogh’s Cabanes de bois parmi les oliviers et cyprès which was part of the Cox Collection.

The Macklowe Collection sale. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

No auction event since the Rockefeller trove at Christie’s was as keenly awaited by the market as the Macklowe Collection. A group of 65 lots was ordered to be auctioned off by a judge as a result of the bitter divorce between real estate developer Harry Macklowe and his ex-wife Linda because the exes couldn’t agree on many valuations. The first half of the trove, 35 lots, was sold on Nov. 15 for $676 million at Sotheby’s, the highest total for a single collection at the auction house. We hear that both Linda and Harry may have been bidding on some of the works, but their representatives declined to comment. The top lot was Mark Rothko’s No. 7, that fetched $82.5 million. A new record was set for Jackson Pollock’s Number 17 painting that sold for $61.2 million and Agnes Martin’s Untitled #44 that went for $17.7 million. The second half is coming to auction in May 2022.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Made in Japan II (1982). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

The market for Jean-Michel Basquiat’s paintings is never dull. While the late artist’s work is often the marquee lot when brought to auction, Sotheby’s contemporary art evening auction saw one of his works fail to sell entirely. Made in Japan II (1982) was estimated at $12 million to $18 million, but bidding failed to even reach that low estimate.

It’s hard to say for certain why any given piece does not find a buyer (of course, an auction house would never dare to make a comment), but a frequent buyer of Basquiat’s work, Christophe Van de Weghe, recently revealed to Artnet News that the market for Basquiat’s work has become too pricey, even for him. This was still a surprising flop however, as Made In Japan II does represent one of the artist’s more iconic themes of skulls, or skull-like portraits. Let that be a testament to the randomness of today’s art market.

Beeple, HUMAN ONE (2021). Courtesy of Christie’s.

It’s been common for years for artists to make specific works for their dealers to bring to specific art fairs. NFTs have inaugurated an era where artists make specific works for specific auctions, advancing the major houses’ long march into becoming primary-market sellers. But HUMAN ONE isn’t just a piece fresh from the studio of Beeple (AKA Mike Winklemann); it’s also his first-ever physical artwork. (Yes, it’s still backed by an NFT.)

Even wilder is that Christie’s paid the artist a house guarantee for the right to consign the mixed-media sculpture, which is embedded with human-sized LED screens that continuously loop randomized animated renderings of a single astronaut trekking through worlds that bridge the familiar and the surreal. But the wildest aspect of all is that the guarantee was a great use of Christie’s cash; the work nearly doubled its $15 million estimate, landing a $29 million winning bid (after fees) from crypto-besotted Swiss financier Ryan Zurrer.

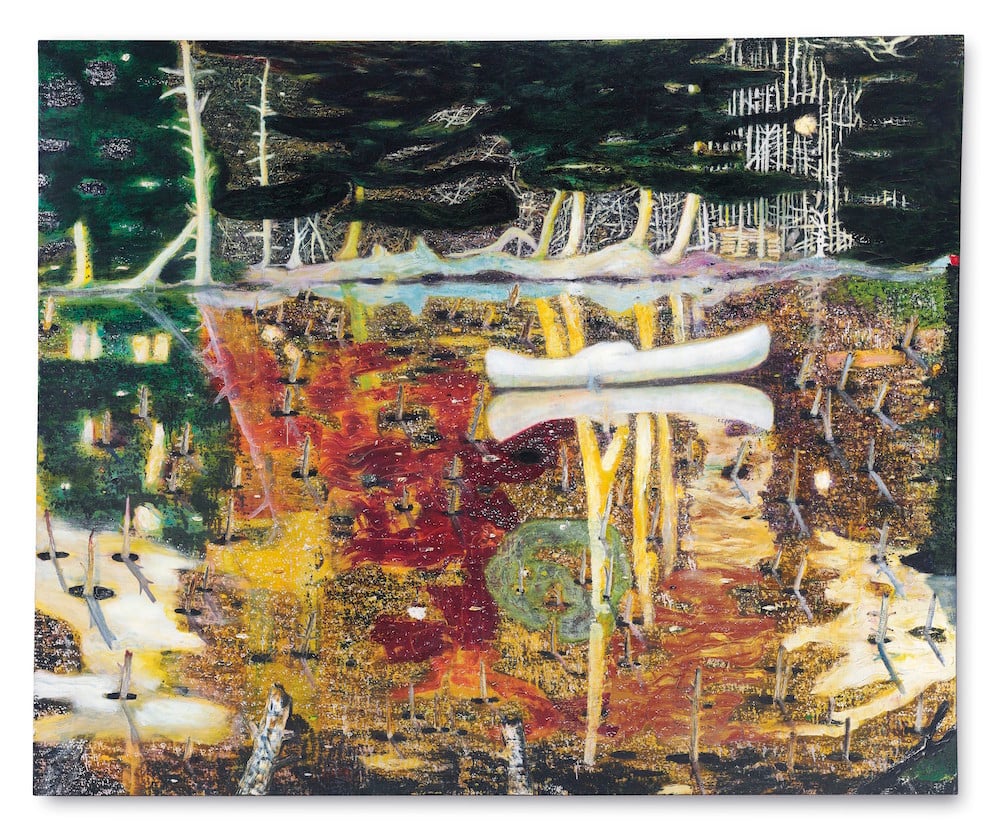

Peter Doig, Swamped (1990). Image courtesy Christie’s.

We’re not going to lie. We love it when prominent artworks in the evening sale have something of a “track record” at auction. It opens up a market window through which to see how far values have risen (or fallen) over the years. In the case of Peter Doig’s classic canoe series painting Swamped (1990), the offering at Christie’s November 9 evening sale marked its third trip to the auction block, after being sold most recently in 2015, and before that in 2002.

“It’s such a well recognized image. It’s as iconic as it gets for Doig and his prime years,” Christie’s senior specialist for 21st-century art, Ana Maria Celis, told Artnet News in the weeks before the sale. At Christie’s New York in 2015, Swamped sold for just under $26 million, which set the record for the artist at the time. (In the 2002 sale, the work sold at Sotheby’s London for just $455,444.)

Doig’s record was broken again in 2017, when another landscape painting, Rosedale (1991), sold for $28.8 million at Phillips New York, which remained the auction high. This time around, Swamped—which was guaranteed and estimated in excess of $35 million—broke that record when it sold for $39.9 million.

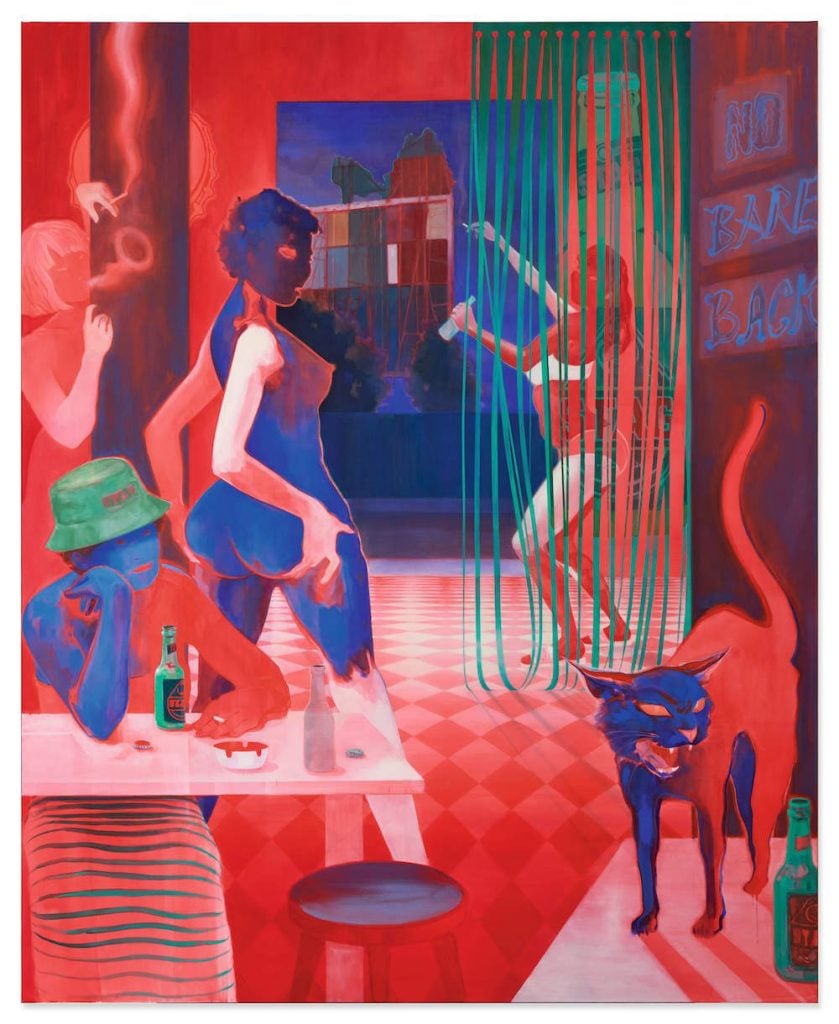

Lisa Brice, No Bare Back, after Embah (2017). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

The Now, Sotheby’s evening auction of emerging art, began with a figurative painting by Lisa Brice, a South African, London-based artist who, it’s safe to say, is not a household name. That may change soon. It was the first time Brice’s work appeared in an evening sale, and the level of demand could be gleaned by the estimated range of $200,000 to $300,000 versus her current auction record of $34,487.

Before the auctioneer had a chance to open the bidding, Sotheby’s specialists hollered: $500,000! $600,000! Then it was off to the races, with so many bids it was hard to count. Ultimately, the painting No Bare Back, after Embah, a bar scene in seductive colors, hammered at $2.6 million, adjusted to $3.2 million after fees were added.

The press hospitality room at Christie’s Rockefeller Center headquarters. Photo by Eileen Kinsella

Phillips served guests champagne, Sotheby’s served wine and champagne and passed hors d’oeuvres while some white-gloved staff sported custom-made face masks that bore the auction house’s distinctive logo. Everywhere there were signs of auctions returning to some semblance of the “before times” IRL experience—but with touches of the new reality apparent.

Christie’s appeared to pull out the stops for guests and press alike. Bottles of spring water with custom made labels read “Welcome Back,” under the Christie’s logo. A jazz trio at the base of the sweeping staircase performed in front of a massive Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Guilt of Gold Teeth (1982), which sold for $40 million. Guests exiting the auction house were handed beautifully packaged Ladurée macarons in the lobby.

Members of the press had a dedicated hospitality room stocked with wi-fi, water, and stamped Christie’s lunch boxes that offered charcuterie, nuts, cookies, and brownies, a much-appreciated source of sustenance amid the marathon sales. Somewhat more inexplicably (but no less welcome as swag goes), the auction house handed out customised cushy socks at the press check-in that had Christie’s logo embroidered on them as well as the words “Icons” in two color patterns.

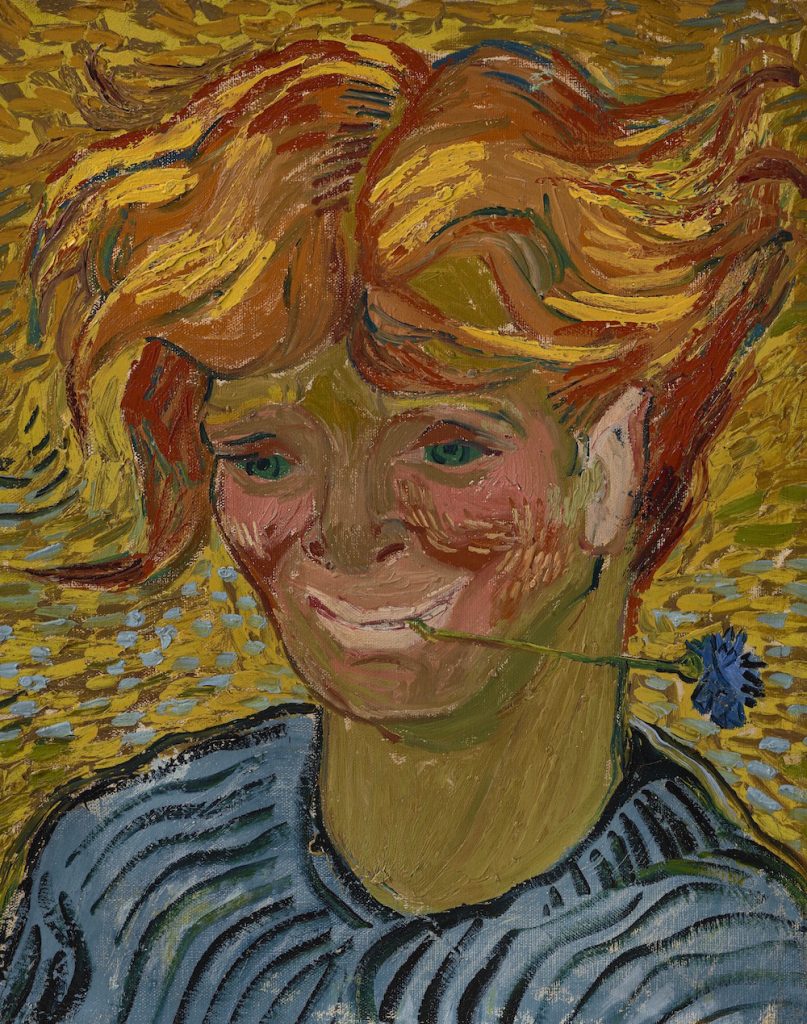

Vincent Van Gogh, Jeune homme au bleuet (1890). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Nine minutes is a long time. It’s the average length of Beethoven’s Piano Concert #2, its apparently the average wait time to get through Chick-Fil-A drive-thru, and it’s how long a bidding war went on at Christie’s sale of the Cox Collection for Vincent Van Gogh’s Impressionist painting Jeune homme au bleuet (1890). Eleven bidders fought tooth and nail for the striking (dare we say…ugly) portrait work that was completed just a few months before the artist’s death in Auvers-sur-Oise. The work finally hammered for $46.7 million over a modest estimate of $5 million to $7 million.

Alberto Giacometti, Le Nez

Conceived in 1947; this version conceived in 1949 and cast in 1965.

Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

The largest uncertainty hovering over the Macklowe Collection was whether its concentration on largely white, largely male postwar artists would appeal to the rising generation of global collectors that has proven so keen on piling millions into the artists of their own time. Collector and dealer Adam Lindemann even went on the record to opine on the Macklowe trove, “Yes, these things are always going to be great, but is this what a young tech billionaire wants? I don’t think so.”

Enter Justin Sun, the Chinese-born, 31-year-old tech billionaire behind web3 infrastructure company TRON. Sun took to Twitter hours after the Macklowe auction concluded to out himself as the winner of Giacometti’s Le Nez, the megasale’s second-priciest lot. He went on to announce his plans to donate the sculpture (and two other recent auction acquisitions) to his APENFT Foundation, where it will be tokenized on the blockchain en route to (eventually) amplifying the cultural offerings in the forthcoming immersive digital reality known as the metaverse. If you saw that one coming, congratulations, you are in a very, very exclusive club.

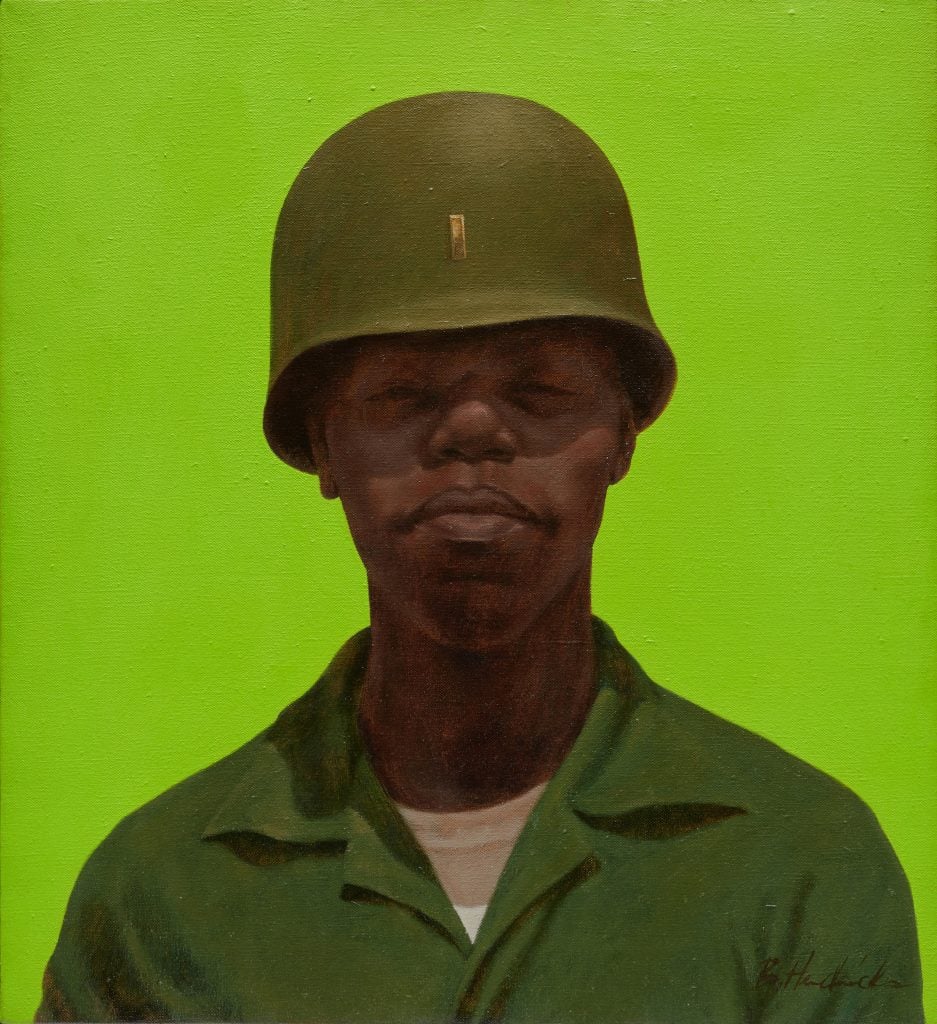

Barkley L. Hendricks, FTA (1968). Courtesy Phillips.

FTA was among the works in this season’s auction cycle whose sales proceeds were earmarked to benefit philanthropic causes, in this case “the pursuit of anti-racism,” according to Phillips’s online catalogue. With a presale estimate of $4 million to $6 million and Hendricks’s considerable market power behind it, the portrait seemed poised to do a lot of good.

That’s why it was all the more disappointing to observers when the house announced before its 20th century and contemporary evening sale that FTA was one of the two lots being withdrawn. Asked after the sale what compelled the eleventh-hour change, Phillips senior specialist and head of day sale, John McCord, said the painting’s owners “were very keen on FTA ending up in a museum, and when it seemed that would likely not be the result, they preferred to withdraw the work.” Phillips is now working with the owner to find an institutional home for the painting. For the sake of anti-racism, let’s hope when the house finds one, it comes with a generous patron willing to pay market price.

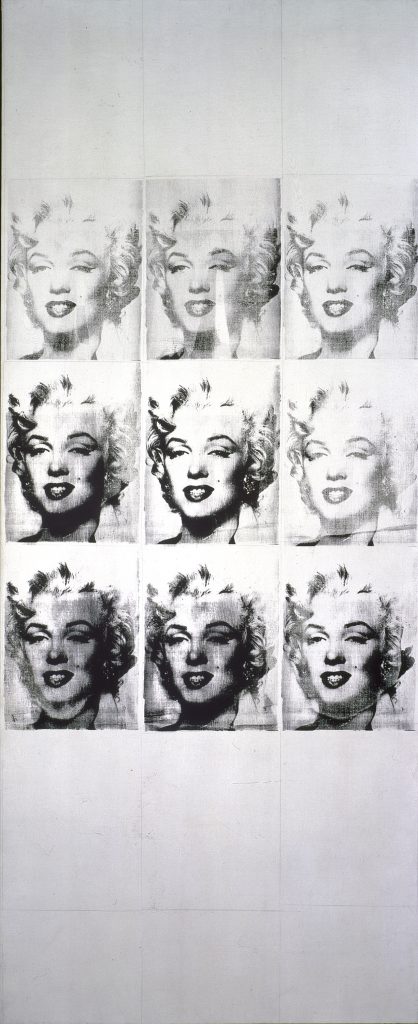

Andy Warhol, Marilyn (9 Times) [Nine Marilyns] (1962). Photo: Richard Gray Gallery.

By end of play, Branczik was out and Hess got the work for $48.2 million. But at the end of the auction, auctioneer Oliver Barker announced he would reopen the lot. When he did, it hammered for just $41 million, to Branczik’s bidder this time. The mistake cost Sotheby’s $1.1 million in lost commissions.