The Back Room

The Back Room: Ghana’s Gameplan

This week: Ghana's hottest talents blaze a new trail, details on a billion-dollar divorce, flippers keep on flipping, and much more.

This week: Ghana's hottest talents blaze a new trail, details on a billion-dollar divorce, flippers keep on flipping, and much more.

Artnet News

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: Ghana’s hottest talents blaze a new trail, details on a billion-dollar divorce, flippers keep on flipping, and much more—all in a 6-minute read (1,684 words).

__________________________________________________________________________

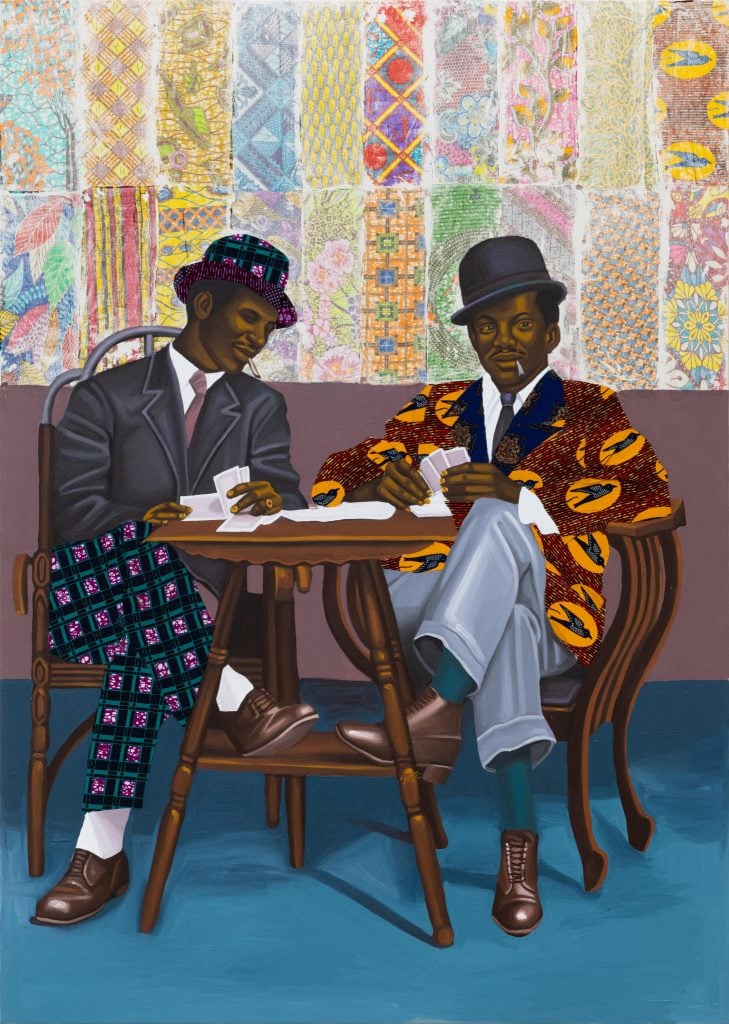

Cornelius Annor, W) ta shi – we have taken our sit,, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and MARUANI MERCIER Gallery

This week, Julie Baumgardner zoned in on the market frenzy for young Ghanaian figurative painters after a perfect storm of speculation catapulted Amoako Boafo’s market into the stratosphere in 2020.

Her novel conclusion: contrary to the common perception, these surging talents have figured out how to flip the script on the flippers, “building wealth for themselves, their community, and Ghana” in the process.

Three years after Boafo’s emergence, the market for his signature finger-painted portraits remains solid. While his auction record has been frozen at $3.4 million since late 2021, his median price under the hammer is $425,000—right in line with the $450,000-and-under primary-market prices for works in his current sold-out show at Gagosian in New York, sources said.

Meanwhile, a growing crop of Ghanaian artists exploring Black figuration have learned from Boafo’s example, just in time for international blue-chip galleries to swoop in…

Four young artists from the country stand out:

Cynics tend to read these gallery relationships as inherently exploitative. In their view, Western dealers are pushing impressionable African artists to churn out incremental variations on a trendy subject fast enough to capitalize handsomely at auction, all while cutting out the homegrown dealers who first took a chance on their vision.

Another camp of observers holds a slightly more charitable view: that the success of young African artists at least helps reorient art history around under-represented, non-Western perspectives—even if the market forces propelling them to fame still carries a high risk of predation.

But Baumgardner sees it another way. “These artists have figured out how to play the global art-market game” to raise up themselves and their homeland, she writes, “without government funding or an organizing body. And most importantly, with their cultural values intact.”

Arguably the most important element of these artists’ rise has been their conscious decision to band together into a recognizable movement. Like any good brand, this one has its clear narrative and stylistic hallmarks.

Like Boafo before them, Annor, Appah, Botchway, and Quaicoe all hail from Ghana. All paint portraits of Black subjects that extend the post-2020 reckoning with a too-white Western canon. Most went to the (now-defunct) Ghanatta College of Art and Design. All began their careers either on the roster, or in the residency, of Accra’s Gallery 1957.

What sets the movement apart, however, is its members’ commitment to paying forward the knowledge and rewards they’ve earned on the international scene, specifically by creating tangible infrastructure for the next generation of Ghanaian artists and art workers…

The familial dynamic plays out in informal ways, too. Several of the Ghanaian artists now surging in the global market maintain a group WhatsApp chat to support and inform one another. They attend one another’s exhibition openings whenever possible. Most of all, they recognize that building something new—and protecting what they’ve achieved—takes action, commitment, and community.

_______________________________________________________________________________

This cohort of Ghanaian painters can be seen as part of a wider grouping of on-the-rise artists from Africa and its diaspora who have responded to systemic imbalances by building, owning, and sharing new arts infrastructure capable of outlasting any market boom.

Springing to mind are another Ghanaian artist, Ibrahim Mahama, who offers residencies and other opportunities through his dual institutions, the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art and Red Clay; Kehinde Wiley, who debuted his Black Rock Senegal residency in Dakar in 2019; and Michael Armitage’s nonprofit Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute in Kenya.

The blueprint also extends to the West. Consider Titus Kaphar’s NXTHVN in New Haven, Connnecticut, and (a generation earlier) Mark Bradford’s Art and Practice in L.A.

No matter each artist’s precise heritage or current geography, it’s patronizing to think that they are naïve to the ways speculation works or how it might be harnessed for the greater good. By shrewdly redistributing some of their gains into new institutions for future generations, they don’t just exploit the would-be exploiters in the short term; they also create a potentially powerful new force against institutional racism for the long term. That’s a legacy worth carving out.

_______________________________________________________________________________

The latest Wet Paint spills details of the divorce settlement between mega-collectors Israel and Caryl Englander, which awarded Caryl “upwards of $1 billion” and a big chunk of their “sizeable” art collection.

Here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries

Institutions

Tech and Legal News

_______________________________________________________________________________

“Commemorating the anniversaries of our greatest artists’ deaths by having comedians that don’t tell jokes curate museum shows about how much of an asshole they were is, I guess, quite funny.”

—Art critic Dean Kissick, roasting the news that post-standup-comic Hannah Gadsby will organize “It’s Pablo-Matic,” a show of 100 works by mostly women artists offering a feminist lens on the now-50-years-dead Pablo Picasso, at the Brooklyn Museum this summer. (Twitter)

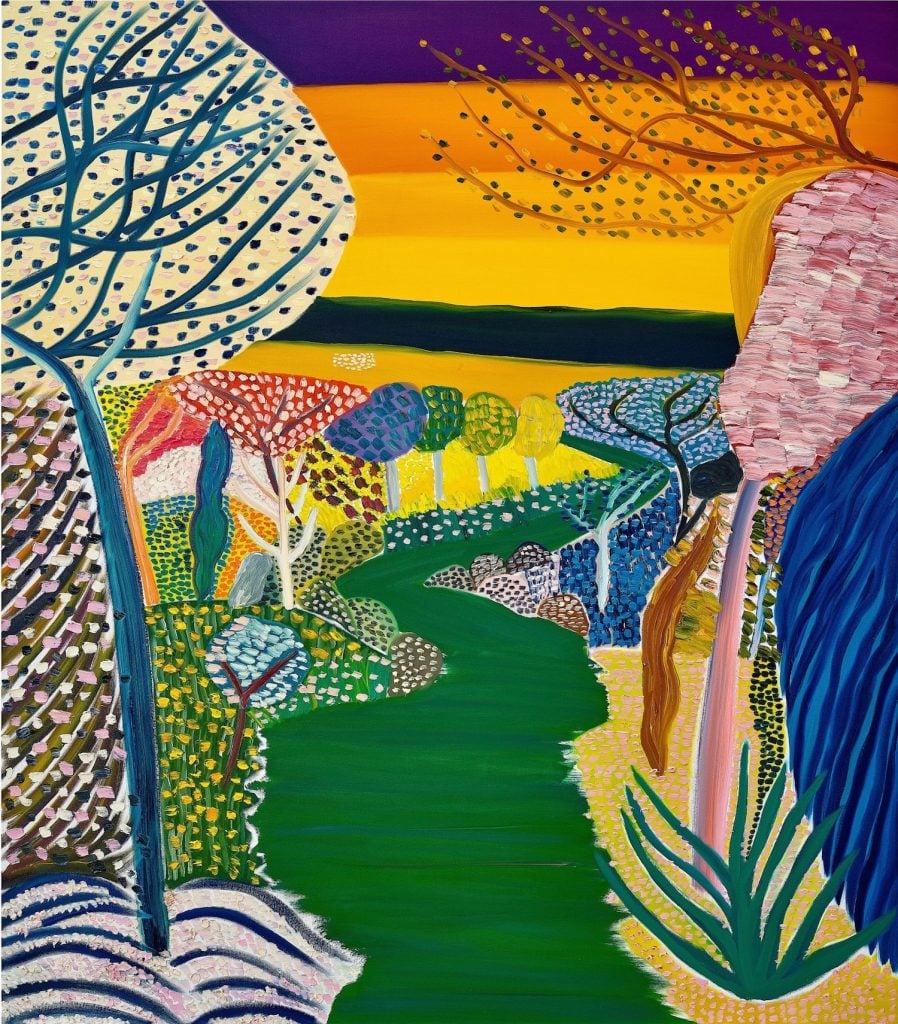

Matthew Wong, River at Dusk (2018). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Date: 2018

_______________________________________________________________________________

Estimate: HK$40 million–60 million ($5.1 million–$7.6 million)

_______________________________________________________________________________

Sold for: HK$52.3 million ($6.7 million)

_______________________________________________________________________________

Sold at: Sotheby’s Hong Kong

_______________________________________________________________________________

Sold on: April 5, 2023

_______________________________________________________________________________

The colorful landscapes of late Canadian artist Matthew Wong, who died by suicide in 2019, have been chased by collectors ever since the artist’s solo show at Karma gallery that same year, when primary-market prices were averaging around $20,000. All that’s changed in the four years since are the speed of the resales and the size of the prices, as this recent offering at Sotheby’s Hong Kong proved once again.

River at Dusk (2018), backed by a third-party guarantee at the April 5 sale, set a new auction record for Wong at HK$52.3 million ($6.7 million). The piece has now been sold three times in its five-year lifespan. After acquiring it from Karma, the original buyer resold the painting only a year after Wong’s death for HK$37.8 million ($4.8 million) at a Phillips/Poly Hong Kong auction in December 2020.

Well, the winning bidder at that sale just snagged a price 40 percent higher by putting River at Dusk back on the auction block less than two and a half years later. So if you entered 2023 thinking that the wobbly global economy would eventually tamp down all the speculative buying, the new warp speed of flipping says that you should think again.

—Eileen Kinsella

_______________________________________________________________________________