The Back Room

The Back Room: The Doig Defection

This week: a different type of Peter Doig solo show, a job posting for the ages, the quick COVID recovery of California's creative class, and much more.

This week: a different type of Peter Doig solo show, a job posting for the ages, the quick COVID recovery of California's creative class, and much more.

Artnet News

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: a different type of Peter Doig solo show, a job posting for the ages, the quick COVID recovery of California’s creative class, and much more—all in a 6-minute read (1,757 words).

__________________________________________________________________________

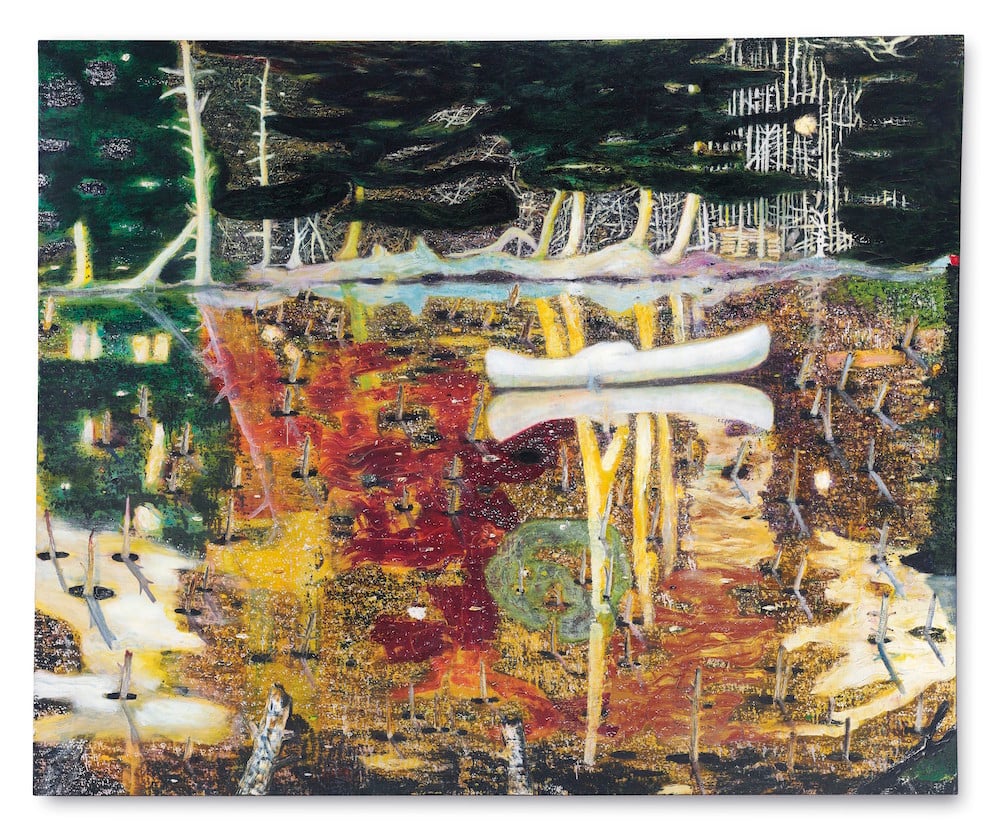

Peter Doig, Swamped (1990). Image courtesy Christie’s.

It isn’t often that one of the world’s most expensive living artists exits their longtime gallery to go independent. But Peter Doig wasn’t afraid to step out, as we learned two weeks back. And what prompted his split with Michael Werner Gallery, his dealer for nearly a quarter-century, has been the talk of the industry ever since.

How sought after is Doig’s work? His auction record stands at $39.9 million, for the sale of Swamped (1990) at Christie’s New York in November 2021. To date, five Doig works have sold for more than $20 million each under the hammer, while 19 works have gone for more than $10 million each, according to the Artnet Price Database.

That’s rare air for a 63-year-old painter still regularly wielding his brushes. Which makes Doig’s decision to fly solo all the more intriguing—though maybe not as lonely as it might sound at first.

Doig’s recently opened solo exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery in London features 12 new paintings, and Werner’s name is nowhere to be found on their wall labels. When asked by our colleague Eileen Kinsella, a representative for the gallery confirmed that it no longer represents Doig.

Neither does any other commercial dealer, it turns out.

“Peter is now working independently and not represented by any gallery,” said Parinaz Mogadassi, the artist’s wife as well as the founder and proprietor of Tramps Gallery on the Lower East Side.

Mogadassi worked with Doig in her previous roles at both Gavin Brown’s Enterprise and at Werner. Her statement makes the Courtauld exhibition the highly unusual case where fresh works went straight from a major artist’s studio to an institution’s walls, with no gallery managing the handoff.

The paintings on view at the Courtauld, some large in scale, include works that were created in the Scottish-born artist’s new studio in London, where he recently relocated from his longtime home in Trinidad. None are for sale at present.

If they were, though, they could add up to more than $10 million in market value. Sources said primary-market prices for Doig’s work tend to run in the seven figures. (The Courtauld show also includes 19 works on paper; some works are loaned from private collections, including that of François Pinault.)

The picture has gotten clearer with time.

One source told Kinsella that Doig simply appeared to be “taking a pause, or a beat.” But another hinted at something deeper, relaying that “the split between painter and gallery had been happening gradually for quite a while, and that the Courtauld show simply had the effect of making it more official,” Kinsella wrote.

Our colleague Annie Armstrong built on this foundation in last week’s Wet Paint. Her conclusion? The breakup stemmed from “slights inflicted by the gallery that [Doig] felt constituted breaches of their relationship.” The water allegedly boiled over fast enough to leave Werner “largely out of the picture for the last stage of exhibition planning” at the Courtauld.

Although Armstrong’s sources alluded to “several signs of a deteriorating relationship” between the gallery and Doig over the course of the pandemic, chief among them seems to be the severing of “financial ties” between Werner and Mogadassi.

Aside from Mogadassi having curated a show for Werner, Tramps had long “acted as a feeder gallery” to the larger dealer. Several artists, including Florian Krewer and Raphaela Simon (both of whom studied under Doig at the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf) and Kai Althoff—were funneled up from Tramps to Werner’s blue-chip operation, with a profit-sharing model governing the exchange.

In 2021, though, the pipeline closed up. “I left for many reasons, but let’s put it this way—when you work with and for others it should feel collegial not conspiratorial,” Mogadassi told Wet Paint via email. (A Werner rep declined to comment, other than to reconfirm Doig’s exit.)

Does anyone but Doig stand to benefit if and when his new paintings at the Courtauld meet the market, to say nothing of whatever he makes next?

For starters, Mogadassi said that Tramps “has collaborated extensively with Doig on projects in the past, and will certainly continue to do so in the future. It is an organic evolution of both the personal and professional relationship between he and I.”

But there’s another figure to consider, too: the super-secretive, super-powerful Joe Hage, the London-based artist manager and partner at law firm Joseph Hage Aaronson. In her February 16 Financial Times column, Melanie Gerlis wrote that Hage “has managed Damien Hirst and Peter Doig for many years and works with other artists and estates.”

Among those others is (or at least, was) at least one more A-lister. Our colleague Kenny Schachter wrote in his most recent column that, “For eons [Hage] served as Gerhard Richter’s gatekeeper.” He went on to venture that Doig may have split with Werner so that Hage could be the one “directly leading the conversations” around his work.

__________________________________________________________________________

Armstrong’s sources downplayed Hage’s importance in motivating the split between Doig and Werner. But the twin presence of Hage and Mogadassi should also remind us that there is a major difference between Peter Doig going without gallery representation, and Peter Doig going it alone.

In that sense, Doig’s divorce from Werner becomes another chapter in the larger story of star artists embracing a new level of autonomy with new types of support, not just hopscotching from one blue-chip dealer to the next when irreconcilable differences arise.

Will Doig and his team push this paradigm even further into new territory? That’s one question that no one can predict yet. But the industry is, and should be, anxiously awaiting the answer.

____________________________________________________________________________

Wet Paint is on break this week, but here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries and Agencies

Institutions

Tech and Legal News

____________________________________________________________________________

“The ideal candidate must be dedicated to a simple goal: make life easier for the couple in every way possible.”

—Excerpt from a since-deleted ad for an executive assistant position on the New York Foundation for the Arts job board. Numerous signs suggest that the post, which was widely ridiculed for its mind-melting gauntlet of responsibilities and $65,000-to-$95,000 salary range, came from art-world power couple Tom Sachs and Sarah Hoover. (Artnet News)

____________________________________________________________________________

Courtesy of the Otis College Report on the Creative Economy 2023.

California’s creative economy largely outperformed both its counterpart in New York and the state of California overall in recovering from the pandemic, according to the latest edition of Otis College of Art and Design’s annual report on the subject.

The trend is visible in the following key findings from the study, which tracks individual and aggregate data across five creative sectors: entertainment; fine and performing arts; architecture and related services; creative goods and products; and fashion.

California’s recovery at the state level is all the more significant because its creative economy dwarfs New York state’s in overall size. For example, California hosted 1.1 million entertainment jobs in 2021, accounting for 4.8 percent of all creative sector employment. Although entertainment jobs in New York made up roughly the same share of the state’s total employment (4.5 percent), they numbered only 542,321—about half as many as their west-coast counterparts.

—Eileen Kinsella