The Art Detective is a weekly column by Katya Kazakina for Artnet News Pro that lifts the curtain on what’s really going on in the art market.

During the early-to-mid 2010s, there was no hotter painter than Christopher Wool.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York filled its entire spiraling rotunda with the artist’s canvases in 2013. The exhibition was supported by major collectors including Tom Hill, Dan Sundheim, and Stefan Edlis.

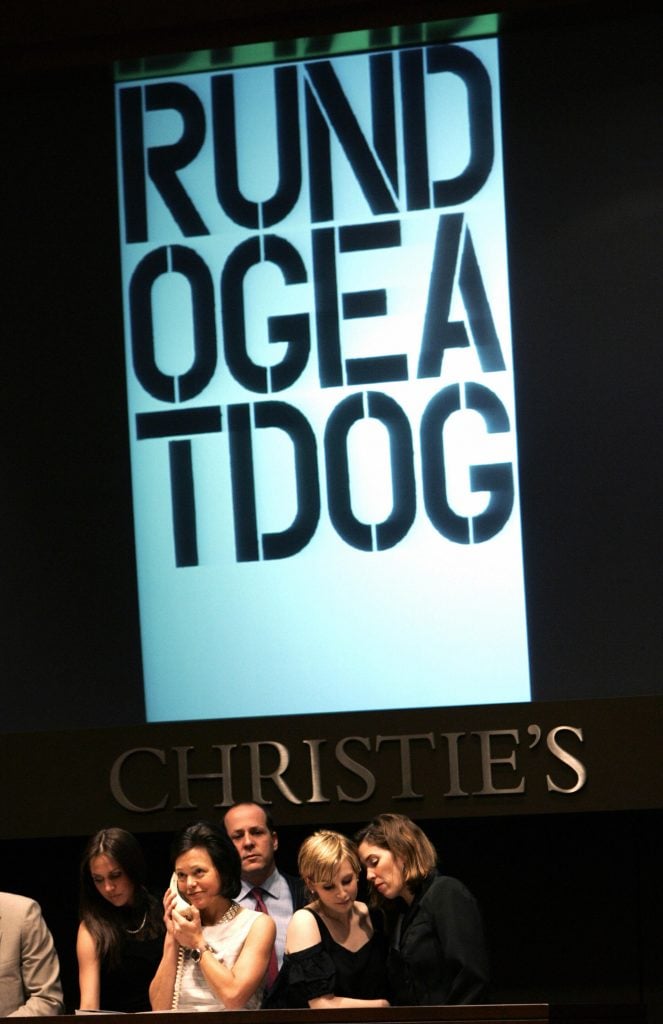

Wool’s painting Apocalypse Now (1988), owned by hedge-fund manager David Ganek and included in the show’s earlier outing at the Art Institute of Chicago, never made it to the Guggenheim. Instead, it headed to Christie’s, where it sold for a whopping $26.5 million, a milestone reached by just a handful living artists.

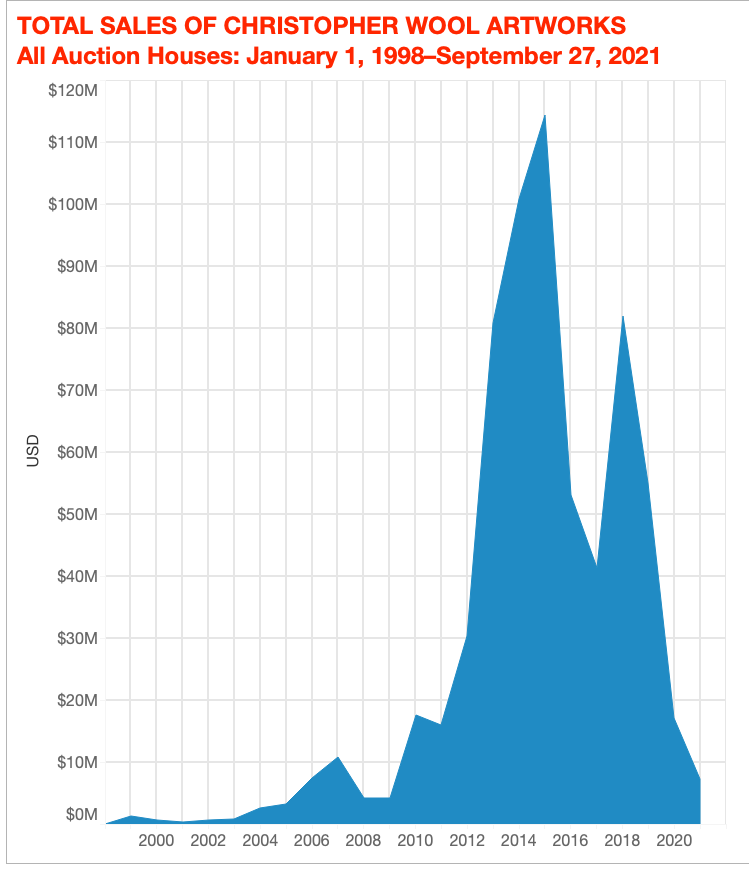

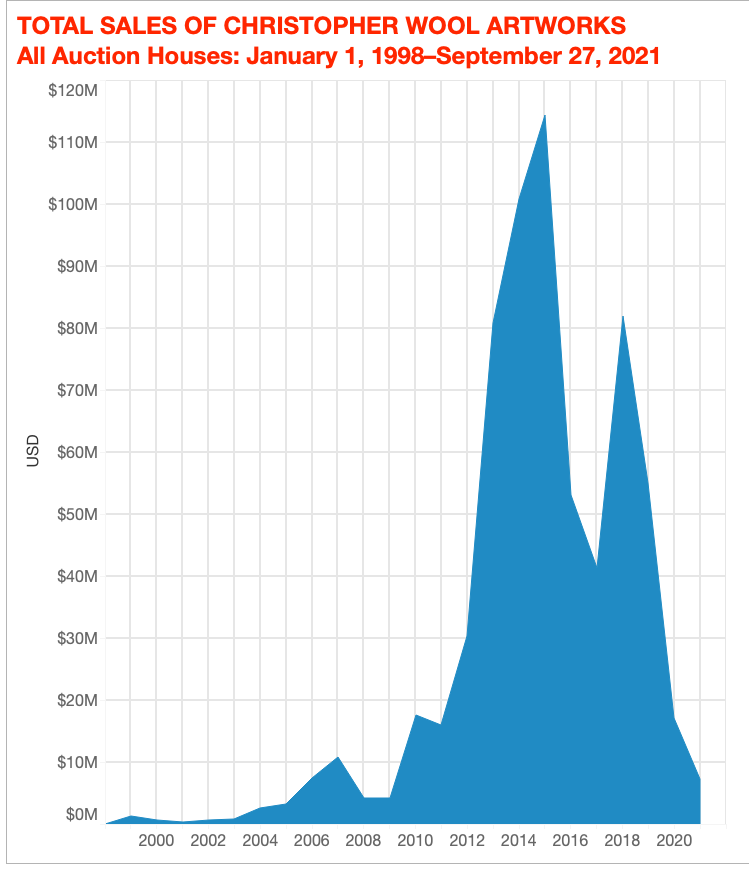

At the time, new works by Wool went for as much as $650,000 at his longtime gallery Luhring Augustine, which kept tight control over access. The dearth of supply sparked a period of intense speculation. By 2015, Wool’s annual auction sales reached $115.3 million—up 3,503 percent from a decade earlier. That year, a painting with the word “RIOT” emblazoned in block letters sold for $29.9 million.

That sale remains the artist’s record to date. Having reached the zenith, Wool’s auction market has gone into contraction mode. In 2016, his total sales fell by more than 50 percent, according to Artnet Analytics. Last year, his work generated just $17 million at auction (almost 85 percent down from the 2015 peak), with 27 percent of lots failing to sell. In May, a text painting spelling “OH OH,” estimated to fetch between $8 million to $12 million, flopped at Christie’s, which had guaranteed it.

© 2021 Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics.

“Nothing goes up forever,” said one dealer, who used to offer secondary-market Wools at major art fairs. “I don’t think you can point to any principal catalyzing factor. It’s just that the work saturated the market and new buyers are not emerging at a rate needed to sustain growing prices. The usual suspects are done collecting Wool for the time being.”

A big test for the artist’s market is just around the corner. Seven works are headed to the auction block at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips during the November auctions in New York, jointly estimated at as much as $34 million.

They arrive at a moment when taste has changed from abstraction to figuration. Collectors, curators, and speculators are more focused on those who have been overlooked, including artists of color and female artists.

Wool’s supporters say that his influence and reputation remain strong even as his auction prices have deflated. Representatives for Luhring Augustine gallery didn’t return calls seeking comment.

“It’s very important to differentiate an artist’s art-historical contribution from the auction market, which has a life of its own,” said Jeffrey Deitch, an art dealer and former museum director. “He’s the definitive abstract painter of his generation.”

Deitch included Wool in a four-artist show, “Strange Abstraction,” in Tokyo in 1991 and in a 2012 show about the history of abstraction at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, during his brief tenure as its director. He sees Wool’s major contribution as marrying the innovations of two great American artists: Jackson Pollock’s overall composition, use of drips, and tension between control and chance with Andy Warhol’s pop language and silkscreen technique.

As Deitch watched Wool’s prices climb into tens of millions, he thought to himself, “This is unsustainable,” he said. “Thirty million [dollars], that’s a price of a great Turner or Picasso from a certain period.”

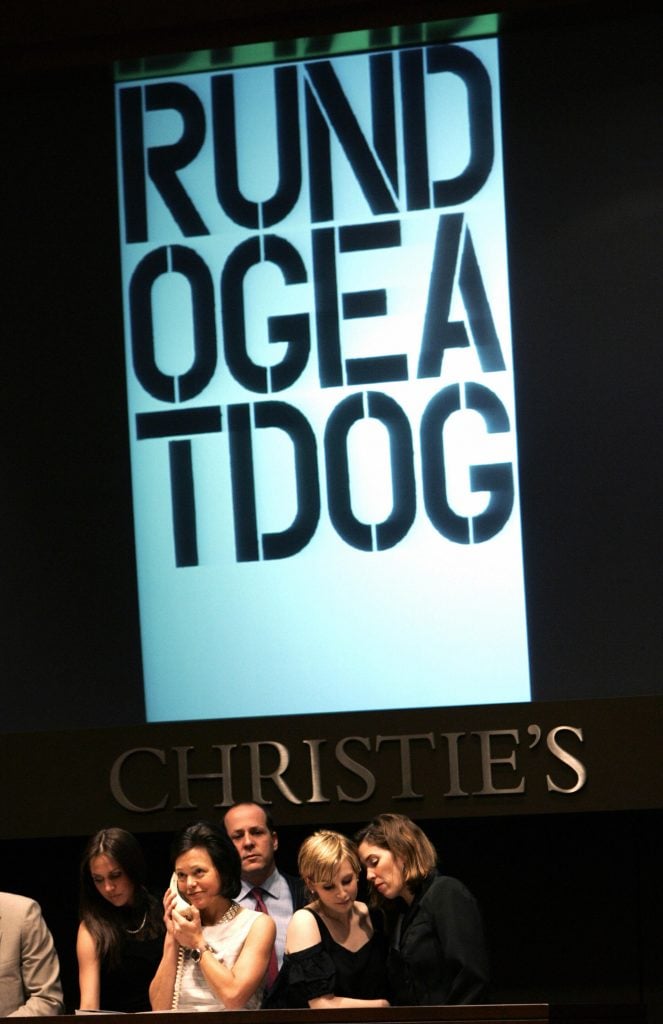

Christopher Wool’s Run Dog Eat Dog at Christie’s postwar and contemporary art sale in May 2006. Photo: Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images.

This season, Christie’s has four Wools, the most of the three houses and possibly a couple too many. Sotheby’s has two, including one from the highly anticipated Harry and Linda Macklowe collection; Phillips has one. Six of the seven have irrevocable bids, meaning they are sure to sell.

All of Christie’s Wools come from the collection of neurosurgeon Abe Steinberger, who is the anonymous consignor of a trove of 1980s art that also includes trophy works by Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince.

In a sign of how much the Wool market has recalibrated since the mid-2010s, one of the works, a 1990 canvas spelling “HA-AH,” carries an estimate of $6.5 million to $8.5 million—significantly less than the $10.4 million it fetched the last time it hit the block at Christie’s London in 2014. (The auction house declined to comment on the identity of the seller, but its provenance suggests that Steinberger acquired it from the person who bought it in London.)

“This is exactly what everybody wanted at the peak,” said Ana Marie Celis, Christie’s senior vice president and head of the 21st century art evening sale. The work is nine feet tall and six feet wide, the same size as the record-setting Untitled (Riot).

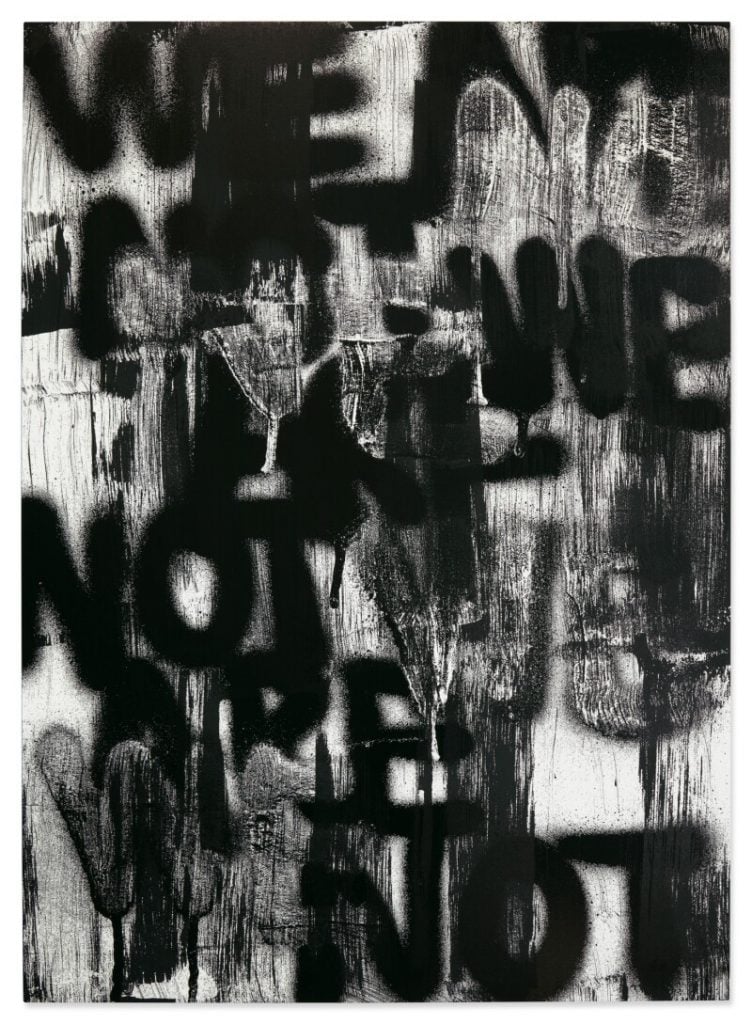

The priciest Wool hitting the block this month, also consigned by Steinberger, is an untitled abstract canvas from 1995, estimated at $7 million to $10 million. The enamel-on-aluminum work in black and white reveals several layers of imagery obscured by smeared, dripping white paint.

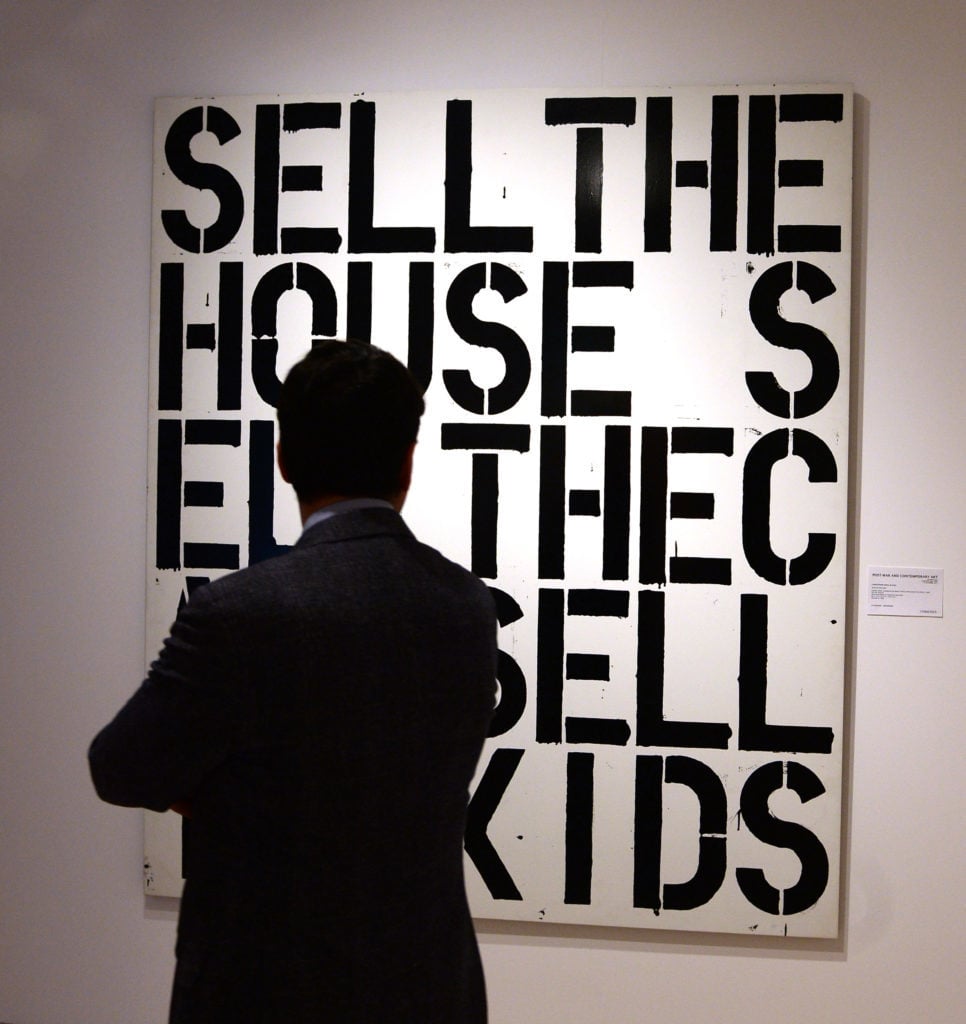

Work by Christopher Wool on view at Christie’s. Photo: Katya Kazakina.

Phillips, meanwhile, has a tiny enamel-on-aluminum word painting, Blue Fool (1990), expected to fetch between $800,000 and $1.2 million. That’s significantly less than the $2 million that Richard Gray gallery was offering it for at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2016. It was purchased there by collector Kenny Schachter, who wrote about the acquisition in his Artnet News column the following year; he declined to comment when reached this week.

The performance of the seven works—two of which are word paintings, the rest abstract compositions—will also show whether buyers continue to prize Wool’s word paintings from the ‘90s above all else, or whether tastes within his oeuvre have also changed. Critics praised his abstract works, which he created with a combination of silkscreen, spray gun, and digital printing, for challenging what a painting can be.

Deitch says that there’s still demand for Wool—albeit at more reasonable price levels. He recently sold a painting to a major client for $6 million, he said. “It’s not frenzied speculation,” he noted. “He has support from really serious collectors.”

Magnifying Glass

Magnifying Glass

A closer look at one work making waves in the market this week

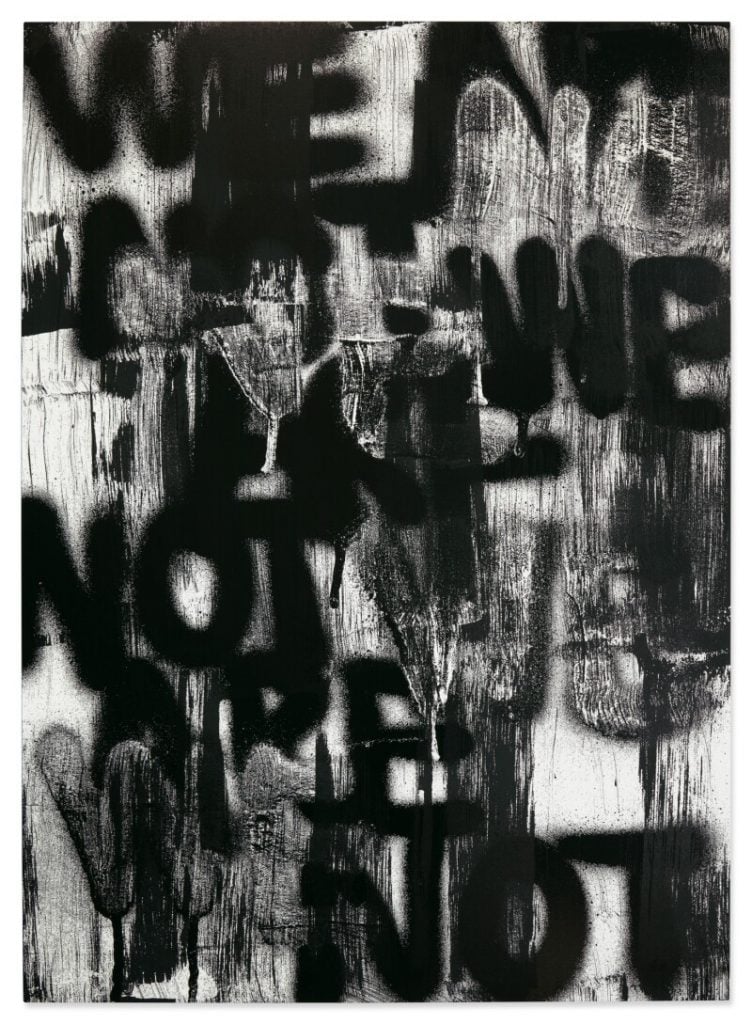

Adam Pendleton, Untitled (WE ARE NOT) (2019–20). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The November sales will also be a test for the market of Adam Pendleton, a conceptual artist whose language-based work is indebted to Wool’s austere black-and-white palette and silkscreen technique.

Sotheby’s scored Pendleton’s Untitled (WE ARE NOT), an eight-foot-tall silkscreen on canvas, estimated at $100,000 to $150,000, for its new “The Now” evening auction on November 18. The 2019–20 work, consigned anonymously, is from the same series as the artist’s current exhibition “Who Is Queen?” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Pendleton’s works are collected by Steve Cohen, Laurene Powell Jobs, Venus Williams, and Leonardo DiCaprio, but relatively few have come up at auction and he has not been subject to the kind of wild speculation that some of his peers have experienced. His $262,812 auction record was set two years ago at a Phillips sale raising funds for a nonprofit organization.

Prices for new paintings start around $200,000. Loïc Gouzer sold a Pendleton painting for $333,000 on his Fair Warning app last year.

Pace, the gallery representing the artist, isn’t happy about the Sotheby’s cameo.

“We didn’t sell it to them to have them sell it again,” said Marc Glimcher, president of Pace gallery. “People generally want to keep them, and we only sell to people who want to keep them. So, if a recent Pendleton comes up at auction, it’s a failure by us to have placed it incorrectly.”

Magnifying Glass

Magnifying Glass